Yuan Dynasty

When the Mongols took control of China, few aristocratic native Chinese joined their government, preferring instead to withdraw from the public sphere and devote themselves to art and literature rather than serve foreign overlords. The most notable exception during the Yuan dynasty was Zhao Mengfu, an accomplished poet as well as a master calligrapher and painter, who held the rank of duke and was an 11th-generation descendant of Zhao Kuangyin, the first Song emperor (Taizu, r. 960–976). In 1286, he became a high government official at the invitation of Kublai Khan himself, and in his official capacity traveled widely and studied the works of many old masters, acquiring a substantial collection of their works. Branded as a traitor by posterity, Zhao nonetheless won universal praise during and after his lifetime for his ability to paint horses, the favorite animal of the Mongols (who conquered China on horseback). So famous was Zhao for his equestrian paintings that over the centuries, collectors and scholars have attributed to him a vast body of work that he certainly did not produce himself.

Zhao’s finesse in capturing the form and personality of different animal species is evident in a small handscroll with an inscription in his own hand stating that he painted Sheep and Goat, a very unusual subject, for a friend and for his personal amusement after he retired from his government position in 1295 and returned to his family home in Wuxing. Relying primarily on dry brushstrokes and ink washes with a minimal use of contour lines, Zhao brilliantly recorded the globular body, thin legs, and dappled coat of the sheep, which turns its head to the left to look at the shaggy-haired goat. In turn, the goat’s animated form and curious expression provide an effective contrast to the almost motionless sheep. Zhao Mengfu’s paintings often incorporate poems he composed and that he presented in elegant cursive calligraphy. Although he stood apart from other Yuan literati because of his government service, Zhao personified the Yuan literati culture, which placed the highest value on poetry, calligraphy, and painting.

Zhao’s wife, Guan Daosheng (1262–1319), was also a successful painter, calligrapher, and poet. Female artists were at least as rare in China at this time as they were in the West, and not only because of women’s similarly restricted roles in society. In China, because calligraphy was so closely allied with painting, and so few women could read or write, the barriers to becoming an artist were even greater. As a general rule, only an educated woman from a well-to-do family could succeed as an artist.

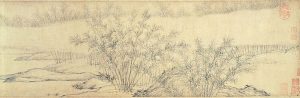

Guan Daosheng won widespread fame in her day and enjoyed the admiration even of the emperor himself. Guan painted a variety of subjects, but she became famous for her paintings of bamboo. The plant was a popular subject because it was a symbol of the ideal Chinese gentleman, who bends in adversity but does not break, and because depicting bamboo branches and leaves approximated the cherished art of calligraphy. Bamboo Groves in Mist and Rain, a handscroll, is one of Guan’s best paintings. The hallmark of her landscapes is the misty atmosphere she achieved by restricting the ink tones to a narrow range and by blurring the bamboo thickets in the distance, suggesting not only the receding terrain but fog as well.[1]

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 1060-61. ↵