Disguised Symbolism

In the early twentieth century, art historian Erwin Panofsky coined the term “disguised symbolism” to describe the symbolism in Northern Renaissance paintings. Symbolism is not disguised in the sense of being secret or concealed. It just means that realistic objects that could naturally be in the scene actually contain deeper symbolic significance that must be decoded by the viewer. Meanings are derived from scriptures, writings of saints and the Church Fathers (St. Augustine, for example), and contemporary sayings. Although many of these meanings are unfamiliar to us today, they would have been well-known to a faithful fifteenth-century Catholic audience.

Campin’s Mérode Altarpiece

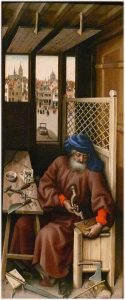

A good example of a Northern altarpiece used for private devotion in a home rather than in a church is the triptych (hinged three panel altarpiece) by Robert Campin, also called the Master of Flémalle. The central panel depicts the Annunciation. In the right wing, Joseph makes mouse traps in his carpentry workshop; in the left, two donors kneel by an open door.

As in contemporary Italian painting, Campin’s figures occupy three-dimensional space and are modeled in light and dark. The light source is consistent and unified. In contrast to contemporary Italian art, however, the Netherlandish painters preferred sharp, precise details, some of which are so small that magnification is necessary to see them clearly. Campin does not use one-point perspective, and each panel is seen from a different viewpoint. The Annunciation takes place entirely indoors whereas in the side panels a distant medieval town is visible.

This altarpiece contains a wealth of complex Christian symbols. In contrast to Italian Annunciations, Campin’s takes place in a bourgeois home, whose everyday, secular objects are endowed with Christian meaning. The lilies represent the purity of the Virgin, and the fact that there are three of them refers to the Trinity. The brass basin and towel are household objects but may also refer to Christ cleansing the sins of the world. At the same time, the niche corresponds to an altar niche, where the priest washed his hands, symbolically purifying himself before Mass. The candle, which has been blown out, can represent Jesus’s Incarnation. Entering the room from the round window on the left wall, a tiny Jesus carrying a cross slides down rays of light. They leave the glass intact, illustrating the popular Christian metaphor that equates the entry of light through a window with the Virgin conception and birth.

In the right panel, the attention to detail and the convincing variety of surface textures – for example, the wood, the metal tools, Joseph’s fluffy beard, and his heavy, simple drapery – reflect Campin’s study of the natural world. The image of Joseph and mousetraps signifies his symbolic role as a trap for the devil: his marriage to Mary was interpreted as a divine plan to fool Satan into believing that Jesus’s father was mortal. Joseph thus protects Mary and Jesus, and so guards the sanctity of the central panel.

The donor has been identified by the coat of arms at the top of the back-wall window of the Annunciation as belonging to the Engelbrecht family from Mechelen. His wife, a figure thought to have been added after their marriage, kneels behind him and holds a string of rosary beads. Husband and wife are privileged to witness the moment of the Incarnation through the slightly open door, but they remain outside the sacred space. The small figure in the background has been variously identified – from the artist himself, to the donor’s patron saint, to Isaiah, whose Old Testament prophecies are the source of several iconographic conventions used in Annunciation scenes.[1]

- Laurie Schneider Adams, Art Across Time, vol. 2, 4th ed., (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011), 514-515. ↵