Francisco Zurbaran, St. Serapion

Soldier, friar, hostage, martyr, saint

Accounts conflict about Serapion’s origins—some say that he was born in England, others in Ireland or Scotland. What is known is that he was a soldier in the army of King Richard I (the Lionheart) and later that of Leopold VI, Duke of Austria. He then went to Spain to participate in the Reconquista (the Christian “reconquest” of parts of the Iberian peninsula—today Spain and Portugal—that had been under Islamic rule) before becoming a friar in the Mercedarian Order. This order was founded in Spain to ransom Christians who had been captured by Muslims. There are several conflicting accounts of Serapion’s martyrdom—one story has him martyred by pirates off the British coast, another says he was left for dead, recovered and then was killed in Algiers. According to the Mercedarians, Serapion made several successful hostage rescues. During the last captive exchange the ransom money took too long to reach Algiers and Serapion was killed. The saint was nailed on an X-shaped cross like the Apostle St. Andrew, and dismembered or disemboweled.

Tenebrist drama

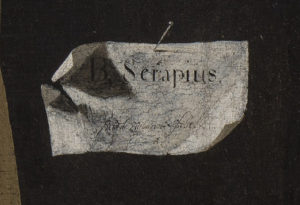

This horrific martyrdom is the subject of this seventeenth-century painting by the Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán. None of the grisly details are evident in this painting—Zurbarán chose to convey this event as a still and contemplative scene. The three-quarter-length figure of Serapion takes up most of the composition; his lifeless body robed in his beige habit emerges from a dark background. The tenebrism (the intense contrast between light and dark) provides a dramatic illumination of the saint’s body and is characteristic of Baroque art in the style of Caravaggio. One can imagine that in a dimly lit room the intensely realistic figure would appear to be emerging from the darkness into the viewer’s space. The only reminder that this is indeed a painting is the small piece of paper where Zurbarán identified Serapion and signed and dated the work.

Monastic patrons

Zurbarán’s realism and austere, spiritual aesthetic made for a style that was well-suited for the quiet and contemplative monastic environment. This particular painting was displayed in a room where deceased monks were laid out before their burial—so in this sense it was a funerary image. Monks reflecting on death would be confronted by this image of martyrdom and all its spiritual connotations.

The Mercedarian Order was founded on the notion of self-sacrifice, ransoming and taking the place of captive Christians. Many in the Order met bloody deaths like Serapion and this element of their origin was ever-present. Zurbarán depicted Serapion with his arms stretched up and tied to a faintly visible tree. His pose is reminiscent of Christ on the cross, and the fact that Serapion willingly risked his life (as did many Mercedarians) echoes Christ’s own sacrifice. Zurbarán favored a largely monochrome color scheme that adds to the subdued tone of the work. The muted browns and cream colors are pierced only by the small yet prominent red and yellow Mercedarian badge on the saint’s torso.[1]

- Dr. Melisa Palermo, "Francisco de Zurbarán, The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed March 15, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/zurbaran-the-martyrdom-of-saint-serapion/ ↵