Introduction to the Bauhaus

In Germany, the creators of the Bauhaus (“House of Building”), which had been founded by Walter Gropius (1883-1969) in Weimar in 1919, found the strict geometric shapes and lines of De Stijl too rigid and argued that a true German architecture and design should emerge organically. At the Bauhaus, Gropius brought together German architects, designers, and craft workers whose collective creative energy could be harnessed to create an integrated system of design and production based on German traditions and styles. Gropius believed that he could revive the spirit of collaboration of the medieval building guilds that had erected Germany’s cathedrals.

Although Gropius’ “Bauhaus Manifesto” of 1919 declared that “the ultimate goal of all artistic activity is the building,” the Bauhaus offered no formal training in architecture until 1927. Gropius’ students were allowed to begin architectural training only after they completed a mandatory foundation course and received full training in design and crafts in the Bauhaus workshops. These included pottery, metalwork, textiles, stained glass, furniture, wood carving, and wall paintings.[1]

Watch this video to learn about the architecture and purpose of the Bauhaus and be prepared to answer questions about it in an upcoming learning check. Start at 3:40 and watch until 20:55.

The Bauhaus[2]

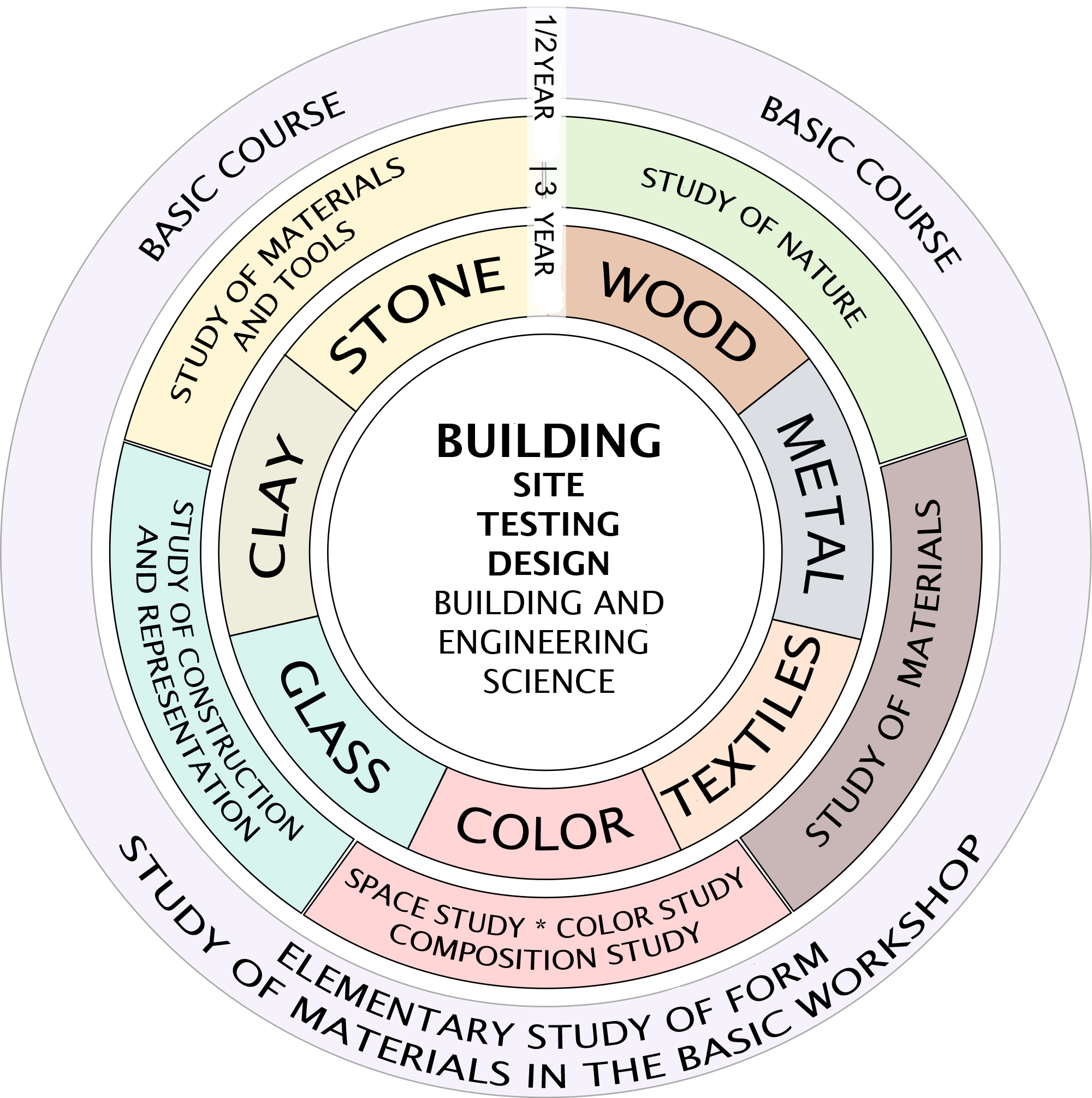

Although it did not have an architecture department until 1927, the 1919 Bauhaus charter called the “complete building” the “ultimate aim of the visual arts.” Architecture requires a unification of all media, both arts and crafts:

In the Bauhaus program of study, diagrammed above as a movement towards the center of a series of concentric circles, all students would start in a half-year or yearlong foundations course in the elements and principles of design, and then each would choose a medium to specialize in: textiles, glass, metal, and so on. The goal was for all of these different specializations to come together in Bau or “building,” the creation of total designed environments, from the structure, to the furniture and tableware, to the rugs on the floor and the paintings on the walls.

The Bauhaus building, Dessau

The most precociously modern of the three main buildings was the shop block, which is sheathed entirely in glass to let in plenty of natural light. The steel frame structure, proudly visible through the transparent walls, has been recessed, allowing the two glass curtain walls to meet at a corner without a masonry joint.

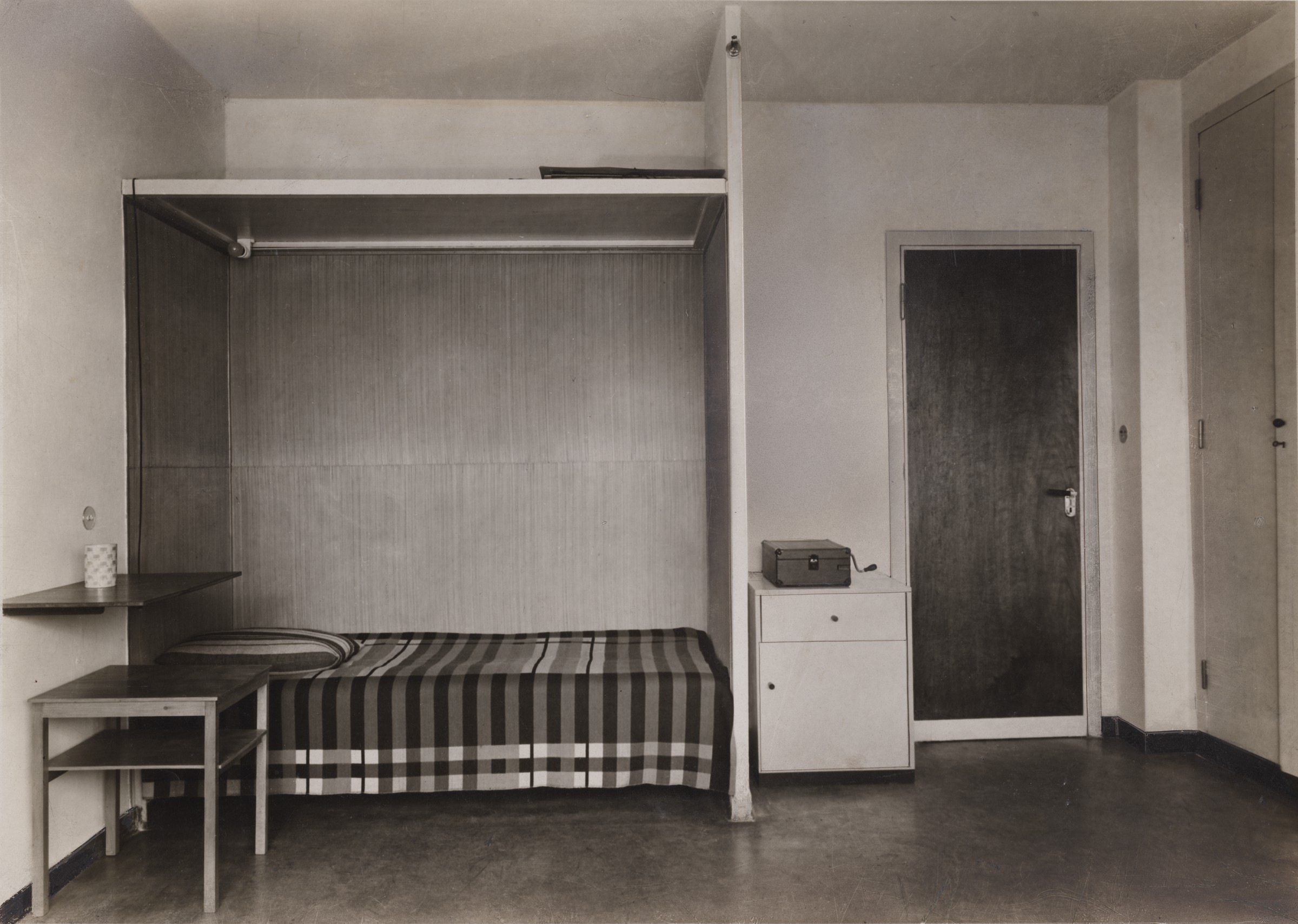

The interior spaces are as starkly geometric and functionalist as the exterior, with the furniture and hardware all designed in the school’s workshops.

Legacy of the Bauhaus

Just seven years after it moved to Dessau, the Bauhaus was forced to move again, this time to Berlin, where it stayed for only one year before being disbanded by the rising Nazi government. Fleeing the unfavorable political environment as well as a disastrous economic situation, Bauhaus students and instructors spread across Europe and the United States, bringing their modern design principles with them. Two of the former directors of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, went to teach in the United States (in Boston and Chicago respectively), where their designs and teaching helped to form the International Style of corporate architecture that now dominates the urban environment.

The promise of the Bauhaus shop block, a building apparently made entirely of glass and steel without the comforting presence of a masonry bulwark, is fulfilled in Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in New York City. Its clear glass ground-floor lobby shows the steel frame and reinforced concrete core that hold the building up, so that its 38-story height appears to stand on stilts. Like the Dessau shop block, there are no decorative flourishes. Mies’s famous motto, “less is more,” embodies the Bauhaus creed that design should be about careful attention to function, materials, engineering, and proportion, not useless decoration. Whether this creed results in livable environments is perhaps a matter of taste, but Bauhaus ideals and designs continue to have an enormous influence today.

- Marilyn Stokstad, Art History, vol. 2, 4th ed, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall: 2011), 1054. ↵

- Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, "The Bauhaus and Bau," in Smarthistory, April 17, 2020, accessed March 2, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/the-bauhaus-and-bau/. ↵