Mughal Art

By 1200, India was already among the world’s oldest civilizations. The art that survives from its earlier periods is almost exclusively sacred, most of it inspired by the three principal religions: Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. These three religions remained a primary focus for Indian art, even as dynasties arriving from the northwest began to establish the new religious culture of Islam.[1]

From the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, the most powerful rulers in South Asia were the Mughal emperors. Mughal, originally a Western term, means “descended from the Mongols,” although the Mughals considered themselves descendants of Timur (r. 1370–1405), the Muslim conqueror whose capital was at Samarkand in Uzbekistan. The Mughal dynasty presided over a cosmopolitan court with refined tastes. British ambassadors, European merchants, and Jesuit priests were frequent visitors, and the Mughal emperors acquired many European luxury goods. They were also great admirers of Persian art and maintained an imperial workshop of painters who, in sharp contrast to pre-Mughal artists in India, often signed their works.

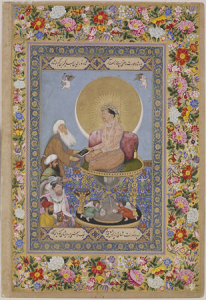

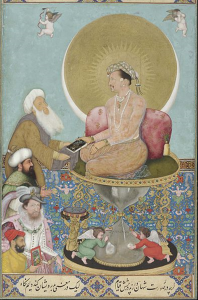

The influence of European as well as Persian styles on Mughal painting is evident in an allegorical portrait of Jahangir (r. 1605–1627), the great-grandson of the founder of the Mughal Empire. The Hindu painter Bichitr represented the emperor seated on an hourglass throne. As the sands of time run out, two putti (clothed, unlike their European models more closely copied at the top of the painting) inscribe the throne with the wish that Jahangir would live a thousand years. Bichitr portrayed his patron as an emperor above time and placed behind Jahangir’s head a radiant halo combining a golden sun and a white crescent moon, indicating that Jahangir is the center of the universe and its light source. One of the inscriptions in the upper and lower borders gives the emperor’s title as “Light of the Faith.” At the left are four figures. The lowest, both spatially and in the social hierarchy, is Bichitr, who wears a red turban and holds a painting representing two horses and an elephant, costly gifts to him from Jahangir. In the painting-within-the-painting, Bichitr bows deeply before the emperor. In the larger painting, the artist signed his name across the top of the footstool Jahangir uses to step up to his hourglass throne. Thus the ruler steps on Bichitr’s name, further indicating the painter’s inferior status. Above Bichitr is a portrait in full European style of King James I of England (r. 1603–1625), copied from a painting by John de Critz (ca. 1552–1642)—a gift the English ambassador to the Mughal court had presented to Jahangir. Above the king is a Turkish sultan (Muslim ruler), a convincing portrayal but probably not a specific likeness. The highest member of the foursome is an elderly Muslim Sufi shaykh (mystic saint). Jahangir’s father, Akbar, had gone to the mystic to pray for an heir. The current emperor, the answer to Akbar’s prayers, presents the holy man with a sumptuous book as a gift. An inscription explains that “although to all appearances kings stand before him, Jahangir looks inwardly toward the Dervishes [Islamic ascetic holy men]” for guidance. Bichitr’s allegorical painting portrays his emperor in both words and pictures as favoring spiritual over worldly power.[2]

Babur

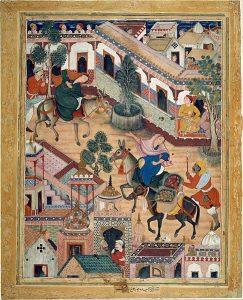

Muhammad Zahir-ud-Din, known as Babur (“Lion” or “Panther”), was the first Mughal emperor of India (r. 1526-30). During his years at the Safavid court, the Mughal emperor acquired a taste for Persian illustrated books. The first great flowering of Mughal art and architecture occurred during the long reign of his grandson, Akbar (r. 1556–1605), called the Great, who ascended the throne at age 14. Like his father, Humayun (r. 1530-1556) Akbar greatly admired the narrative paintings produced at the Safavid court, and he resolved to establish his capital as a great art center. To achieve that goal, the young ruler enlarged the number of painters in Humayun’s imperial workshop to about a hundred, employing many Hindu and Jain artists, and kept them busy working on a series of ambitious projects in which they transformed Persian painting both thematically and stylistically.

One of their projects was to illustrate the text of the Hamza Nama—the story of Hamza, Muhammad’s uncle—in some 1,400 large paintings on cloth. The assignment took the Mughal workshop 15 years to complete. The illustrated books and engravings that traders, diplomats, and Christian missionaries brought from Europe to India also fascinated Akbar.[3]

Miniature Painting

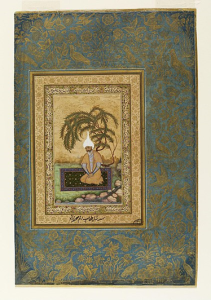

Although India had a tradition of mural painting going back to ancient times, the most popular form of painting under the Mughal emperors and Rajput kings was miniature painting. Art historians usually call these paintings miniatures because of their small size (about the size of a page in a typical art book) compared with paintings on walls, wood panels, or canvas, but the original terminology derives from the red lead (miniatum) used as a pigment. The artists who painted the Indian miniatures designed them to be held in the hands, either as illustrations in books or as loose-leaf pages in albums. Indian artists used opaque watercolors and paper (occasionally cotton cloth) to produce their miniatures. For minute details, the painters used brushes with a single hair. Painters of miniatures sat on the ground, resting their painting boards on one raised knee. Each pigment color was in a separate half seashell. The paintings usually required several layers of color, with gold always applied last. The final step was to burnish the painted surface. The artists accomplished this by placing the miniature, painted side down, on a hard, smooth surface and stroking the paper with polished agate or crystal.[4]

Understanding divine “blueness” in South Asia

Students often ask: “Why is Vishnu blue? Why is Krishna blue?” There are a variety of responses that can be found in the diverse literature and art of South Asia which can help us begin to answer these questions. Here are a few popular understandings for representations of divine “blueness”:

Vishnu has a blue or dark complexion because he reflects the color of the cosmos. Vishnu’s complexion is also understood to be the color of dark storm clouds and the color of the moon. Some scholars believe that Vishnu’s “blueness” is a result of Krishna’s dark complexion, as Krishna is an avatar of Vishnu. In other words, it may be that Krishna’s “blueness” came first. Krishna is known as “the dark one” and his name translates as “black” or “dark” in Sanskrit (also spelled Kṛṣṇa).

Krishna’s complexion may also be related to moments during his life when he drank poison as an attempt to vanquish evil forces or purify the world. One story related to Krishna as a baby describes him sucking the poisoned milk from a bird-demoness who disguised herself as a beautiful woman and visited the baby soon after he was born, in an attempt to kill him. Some believe the poison caused his skin to turn dark or blue.

Blue minerals and pigments—such as aquamarine, indigo, and lapis lazuli—have long been culturally and commercially valuable materials, not only in South Asia, but also around the world. The choice to depict Krishna as blue (rather than black) may have been a result of the availability and popularity of these materials.[5]

Krishna Holds up Mount Govardhan

- Marilyn Stokstad, Art History, vol. 2, 4th ed, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall: 2011), 772. ↵

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 1, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2010), 1043. ↵

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 1, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2010), 1046-47. ↵

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 1, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2010), 1047. ↵

- Dr. Cristin McKnight Sethi, "Understanding divine “blueness” in South Asia," in Smarthistory, August 15, 2021, accessed March 21, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/understanding-divine-blueness-in-south-asia/. ↵