Imperial Chinese history is marked by the rise and fall of many dynasties and occasional periods of disunity, but overall the age was remarkably stable and marked by a sophisticated governing system that included the concept of a meritocracy. Each dynasty had its own distinct characteristics and in many eras encounters with foreign cultural and political influences through territorial expansion and waves of immigration also brought new stimulus to China. China had a highly literate society that greatly valued poetry and brush-written calligraphy, which, along with painting, were called the Three Perfections, reflecting the esteemed position of the arts in Chinese life. Imperial China produced many technological advancements that have enriched the world, including paper and porcelain.[1]

Chinese landscape painting

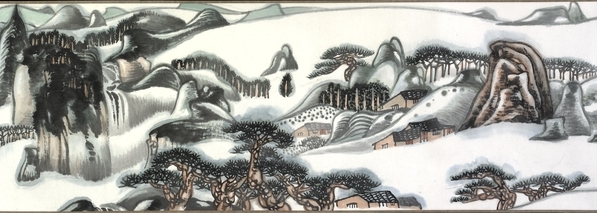

Landscape painting is traditionally at the top of the hierarchy of Chinese painting styles. It is very popular and is associated with refined scholarly taste. The Chinese term for “landscape” is made up of two characters meaning “mountains and water.” It is linked with the philosophy of Daoism, which emphasizes harmony with the natural world.

Idealized landscapes

Chinese artists do not usually paint real places but imaginary, idealized landscapes. The Chinese phrase woyou expresses this idea of “wandering while lying down.” In China, mountains are associated with religion because they reach up towards the heavens. People therefore believe that looking at paintings of mountains is good for the soul.

Chinese painting in general is seen as an extension of calligraphy and uses the same brushstrokes. The colors are restrained and subtle and the paintings are usually created in ink on paper, with a small amount of watercolor. They are not framed or glazed but mounted on silk in different formats such as hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves and fan paintings.

The earliest landscapes

In China, the earliest landscapes were portrayed in three-dimensional form. Examples include mountain-shaped incense burners made of bronze or ceramic, produced as early as the Han Dynasty. The earliest paintings date from the sixth century. Before the tenth century, the main subject was usually the human figure.

In the period following the Han Dynasty, Buddhism spread across China. Artists began to illustrate stories of the life of the Buddha on earth and to create paradise paintings. In the background of some of these brightly colored Buddhist paintings, it is possible to see examples of early landscape painting.

This scene is one of a series of three representing the life of the historical Buddha, Prince Sakyamuni, when he lived on earth. The mountains are simple triangles, and their ridges are painted with short brush strokes to create texture. The water in the river is portrayed in a bold, diagrammatic way, conveying a sense of movement.

Chinese paintings are usually created in ink on paper and then mounted on silk. This is done using different formats including hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves, and fan paintings.[2]

Mountings of Chinese paintings: scrolls, fans, and leafs

The hanging scroll

Chinese paintings are usually created in ink on paper and then mounted on silk. This is done using different formats including hanging scrolls, handscrolls, album leaves, and fan paintings.

Hanging scrolls are typically used for vertical compositions. They are hung for display using a cord, which is attached to a thin wooden strip along the top of the silk mounting. There is a wooden rod at the bottom which provides the necessary weight for the painting to hang smoothly. It is also useful when the painting is rolled up for storage.

The handscroll

Paintings in China are not usually hung on walls, permanently on display. They are often mounted as handscrolls, rolled up and only brought out for special viewings. This is partly due to the delicate nature of the ink and color, which would fade if left exposed to light for a long time. The unrolling of a scroll is an act of some ceremony. Connoisseurs do not view the painting from a distance, as in the West, but approach close to ‘read the painting’.

Handscrolls are designed to be unrolled, from right to left, revealing one scene at a time. As each new section is unrolled, the previous scene is rolled up, giving the viewer the feeling of a journey through the landscape.

The fan

Chinese fans are often decorated with landscapes. Two types of fan are used: the first is nearly circular and made of stiffened silk mounted on a bamboo stick. The second type is curved and folding, made of paper mounted between thin bamboo sticks. This folding type was introduced to Europe from China.

Fan paintings were often created as gifts for a particular occasion and many are dated. Their size made them ideal as presents. Many also include calligraphic inscriptions from friends and comments on the painting.[3]

© Trustees of the British Museum

- Museum, T. B. (2022, April 6). Imperial China, an introduction – Smarthistory. Imperial China, an Introduction – Smarthistory. from https://smarthistory.org/imperial-china-an-introduction/ ↵

- The British Museum, "Chinese landscape painting," in Smarthistory, February 28, 2017, https://smarthistory.org/chinese-landscape-painting/ ↵

- The British Museum, "Mountings of Chinese paintings: scrolls, fans, and leafs," in Smarthistory, June 14, 2016, https://smarthistory.org/mountings-chinese-paintings/. ↵