Synthetic Cubism

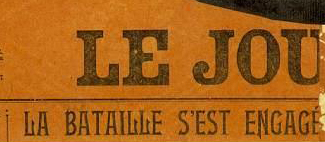

Pablo Picasso’s Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass is generally thought to have been made as a response to Georges Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass. Both works bring a new tool into the already-complex collection of Cubist techniques of representation — the use of collage.

A wealth of associations

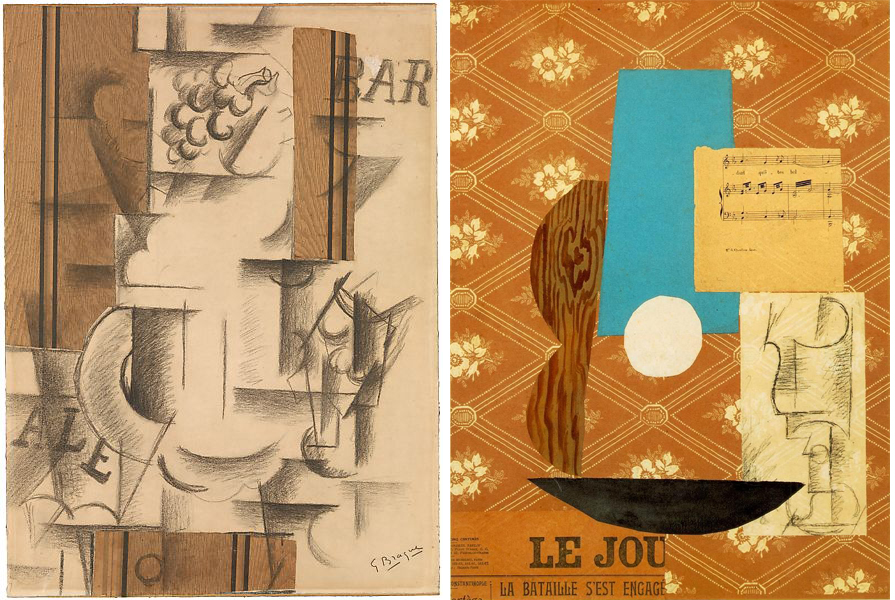

The subject of Picasso’s Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass is familiar from earlier Analytic Cubist paintings, which frequently depict café tables with drinks, newspapers, and musical instruments. Here, however, the abstracted geometric forms of Analytic Cubism are limited to the charcoal drawing of the glass on paper pasted on the right. It is one element in the collage, which includes seven different types of paper arranged on a wallpaper ground.

The pattern of the wallpaper is a diagonal lattice that frames flowers and recalls the overall patterns of lattices and grids that structure earlier Analytic Cubist paintings such as Braque’s Piano and Mandola.

While Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass used only one type of pasted paper (the printed wood grain), Picasso uses many, and demonstrates that a wealth of associations can be generated from their juxtaposition.

Patterns of formal relations

An intricate pattern of formal relations is created between the varied shapes and colors of the pasted paper, which also generate a complex set of possible readings. The guitar is signified by multiple cut-paper elements.

On the left, the hand-painted wood grain paper cut into a double curve suggests the material and shape of the guitar’s body. A vertical trapezoid of blue paper is the neck in perspective, while the shallow black curve below stands for both the bottom of the guitar and the leading edge of the circular table on which the still-life sits.

In the center of the image, the white paper circle representing the sound hole in the guitar body looks like a hole cut out of the picture, while the fragment of sheet music simultaneously refers to itself, and to the sounds emanating from the instrument.

The glass drawn in charcoal is somewhat overwhelmed by the strong shapes of the pasted papers, but its ghostly appearance, as well as the semi-transparency of the paper on which it is drawn, suggests the transparency of glass. It is brought into the composition by the use of a visual rhyme — the circular lip of the glass directly echoes the white circle of pasted paper to the left.

The importance of text

One topic of debate among art historians has been the importance of the legible texts in Cubist collages. In this instance, it is generally agreed that the newspaper text in the lower left is relevant. The headline “La Bataille s’est engagé” (the battle has begun) is from an article about the Balkan War, but it is often interpreted as a competitive challenge to Braque, referring to the use of papier collé. In that reading, this work is a direct response to, and attempt to one-up, Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass.

The truncated masthead of the newspaper “LE JOU” (short for le journal, French for “the newspaper”) is also meaningful. It appears in many Cubist works and not only signifies the newspaper’s presence in the still life, but also a pun on the French words for “to play” (jouer) and “toy” (le jouet). This is a verbal echo of the many formal rhymes and visual puns that appear in Synthetic Cubist works. These allow for multiple readings of individual elements and the relationships between them.

In Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass, for example, “LE JOU” also recalls the French word for day (le jour), and suggests another reading for the forms in the work. The circle of white paper overlapping the trapezoid of blue paper above it can be interpreted as representing not only a guitar’s sound hole and neck, but as the sun rising into the sky at the beginning of a new day. Battles often begin at dawn, and the paired juxtaposition of the papier collé guitar and the Analytic Cubist drawing of a glass suggests a competition between older and newer Cubist techniques.

In their collages Picasso and Braque avoided conventional, often expensive, art materials and overt displays of technical skill that would indicate artistic training. Prior to its use by Braque and Picasso, collage was primarily a craft technique used by women and hobbyists in the 19th century to make scrapbooks. Collages are “poor” art works that do not employ the professional artist’s traditional manual skills.

An enormous influence

For many people the appeal of early Cubist collage and papier collé is more intellectual than conventionally aesthetic. These works prompt the viewer to enjoy the multiple references and significations to be found in the combinations of forms and punning texts, rather than displaying the sensuous qualities of the painted surface or the artist’s skilled touch.

Despite its somewhat arcane intellectual appeal, however, Cubist collage had an enormous influence on modern art in the 20th century. Its employment of simplified planar forms was instrumental in the establishment of non-representational art, especially the geometric abstraction of movements such as Suprematism, Constructivism, De Stijl, Color Field painting, and Minimalism.[1]

- Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, "Synthetic Cubism, Part II," in Smarthistory, November 24, 2019, accessed March 15, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/synthetic-cubism-part-ii/ ↵