Germany and the Graphic Arts

Printmaking emerged in Europe at the end of the fourteenth century with the development of printing presses and the increased local manufacture and wider availability of paper. The techniques used by printmakers during the fifteenth century were woodcut and engraving. Woodblocks cut in relief had long been used to print designs on cloth, but only in the fifteenth century did the printing of images and texts on paper and the production of books in multiple copies of a single edition, or version, begin to replace the copying of each book by hand. Both hand-written and printed books were often illustrated, and printed images were sometimes hand colored. Large quantities of single-sheet prints were made using woodcut and engraving techniques. Often artists drew the images for professional woodworkers to cut from the block.

Woodcuts and Engravings

Woodcuts are made by drawing on the smooth surface of a block of fine-grained wood, then cutting away all the areas around the lines with a sharp tool called a gouge, leaving the lines in high relief. When the block’s surface is inked and a piece of paper pressed down hard on it, the ink on the relief areas transfers to the paper to create a reverse image. The effects can be varied by making thicker and thinner lines, and shading can be achieved by placing the lines closer or farther apart.

Watch this video to see a demonstration of the process of creating a woodcut.

Devotional images were sold as souvenirs to pilgrims at holy sites. The Buxheim St. Christopher was found in the Carthusian Monastery of Buxheim, in southern Germany, glued to the inside of the back cover of a manuscript. St. Christopher, patron saint of travelers and protector from the plague, carries the Christ Child across the river. His efforts are witnessed by a monk holding out a light to guide him to the monastery door but ignored by the hardworking millers on the opposite bank. Both the cutting of the block and the quality of the printing are very high. Lines vary in width to strengthen major forms. Delicate lines are used for inner modeling (facial features) and short parallel lines are used to indicate shadows (the inner side of draperies).

Engraving on metal requires a technique in which the lines are cut into the plate with tools called gravers or burins. The engraver then carefully burnishes the plate to ensure a clean, sharp image. Ink is applied over the whole plate and forced down into the lines, then the plate’s surface is carefully wiped clean of the excess ink. When paper and plate are held tightly together by a press, the ink in the recessed lines transfers to the paper.

Watch the first half of this video to see a demonstration of creating engravings and etchings, two intaglio printmaking techniques. We will discuss Albrecht Dürer and his developments with etchings in a future module.

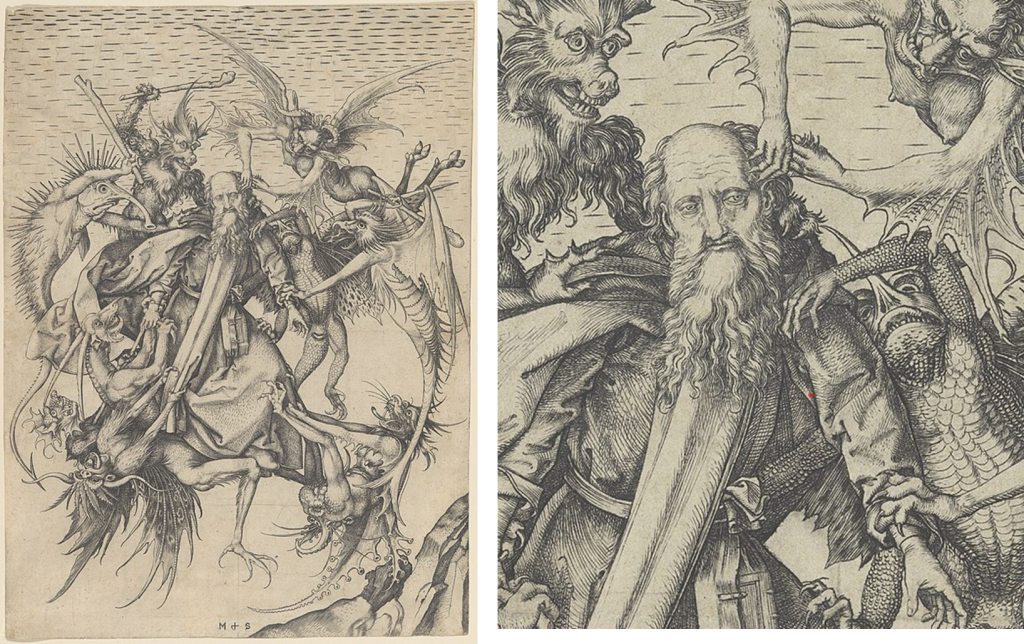

Engraving may have originated with goldsmiths and armorers, who recorded their work by rubbing lampblack into the engraved lines and pressing paper over the plate. German artist Martin Schongauer (c. 1435-1491), who learned engraving from his goldsmith father, was an immensely skillful printmaker who excelled both in drawing and in the difficult technique of shading from deep blacks to faintest grays using only line.

In Demons Tormenting St. Anthony, engraved about 1470-1475, Schongauer illustrated the original biblical meaning of temptation as a physical assault rather than a subtle inducement. Wildly acrobatic, slithery, spiky demons lift Anthony up off the ground to torment and terrify him in midair. The engraver intensified the horror of the moment by condensing the action into a swirling vortex of figures beating, scratching, poking, tugging, and no doubt shrieking at the stoical saint, who remains impervious to all, perhaps because of his power to focus inwardly on his private meditations.[1]

- Marilyn Stokstad, Art History, vol. 2, 4th ed, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall: 2011), 589-590. ↵