The Formation of a French School: the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture

The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) was established in 1648. It oversaw—and held a monopoly over—the arts in France until 1793. The institution provided indispensable training for artists through both hands-on instruction and lectures, access to prestigious commissions, and the opportunity to exhibit their work. Significantly, it also controlled the arts by privileging certain subjects and by establishing a hierarchy among its members. This hierarchical structure ultimately led to the Académie’s dissolution during the French Revolution. However, the Académie in Paris became the model for many art academies across Europe and in the colonial Americas.

To become a member, artists submitted work for evaluation by academicians, who accepted them at a certain level, based on the kind of subjects they aspired to paint. If they passed this first phase, applicants would execute a “reception piece” depicting a subject chosen by the academicians.

The Académie divided paintings into five categories, or genres, ranked in terms of difficulty and prestige:

- History Painting—encompassing highbrow subjects taken from the classical tradition, the bible, or allegories, this type of painting was considered the highest genre because it required proficiency in depicting the human body, as well as imagination and intellect to depict what could not be seen. These were often large-scale multi-figure paintings.

- Portraiture—focusing on capturing likeness, this genre was prestigious, and certainly lucrative, but less so than history painting. Portraitists were derided for “merely” copying nature rather than inventing (an oversimplification as few portraits were executed entirely from life).

- Genre Painting—depicting scenes of everyday life, this genre included the human figure but ostensibly did not represent grand ideas, although many genre paintings had moralizing undertones. Genre paintings were smaller in size than history paintings, further detracting from their prestige.

- Landscapes—consisting of all representations of rural or urban topography, real or imagined, this genre became especially popular during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

- Still Life Painting—often indulging in the juxtaposition of colors and textures, these paintings represented inanimate (often luxury) objects and drew heavily on the seventeenth-century Dutch tradition of such subjects. While at times other moralizing symbols such as memento mori (reminders of human mortality) were included, these were not an intrinsic part of the genre, which was considered to require no invention on the part of the artist (since, they were painting what they could see).

Training

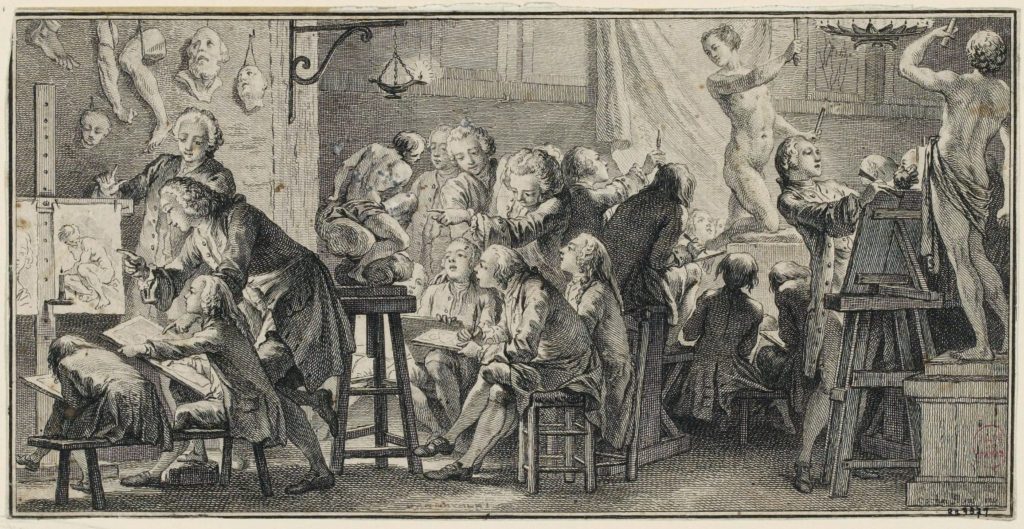

An etching illustrating a 1763 description of the “school of art” shows how students first learned to draw by copying drawings and engravings (seen on the left) before moving on to drawing plaster casts to learn how to translate the three-dimensional form into two dimensions (seen at center). Students would then copy large-scale sculpture (as seen at the right-most edge) before being allowed to draw the live nude model (as seen in the middle-right portion, slightly set back from the foreground). Drawing the male nude form was the bedrock of the Académie’s curriculum, an essential building block for painters, particularly those destined to produce history paintings.

Salons and the rise of public opinion

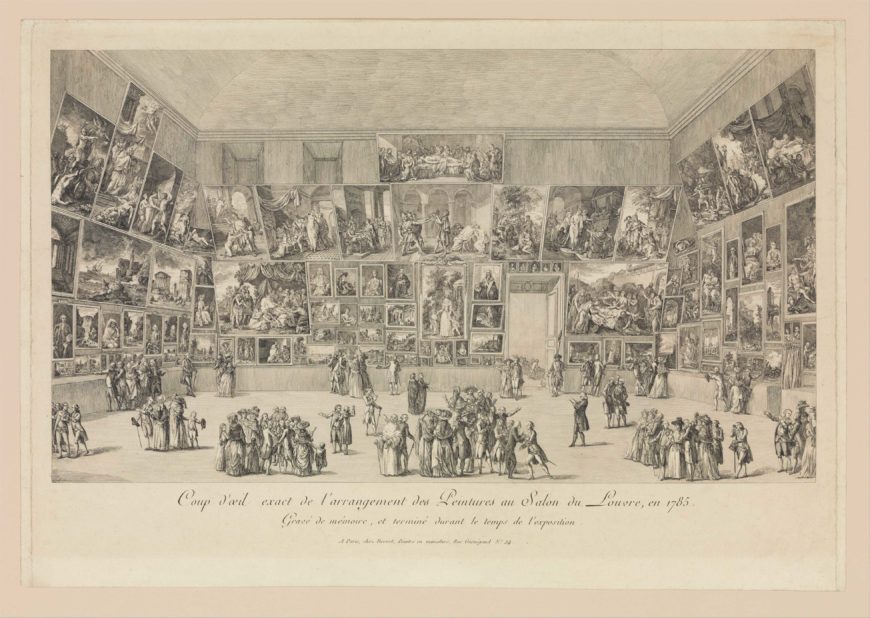

Beginning in 1667, the Académie established exhibitions to provide members with the crucial opportunity to display their work to a wider audience, thereby cultivating potential patrons and critical attention. Held annually and, later, biannually, these exhibitions came to be known as Salons, after the Louvre’s salon carré where they took place after 1725. The Salon became a significant space of artistic exchange and an important opportunity to view art prior to the formation of the public art museum.[1]

- Daniella Berman, "The Formation of a French School: the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture," in Smarthistory, September 2, 2020, accessed March 15, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/royal-academy-france/ ↵