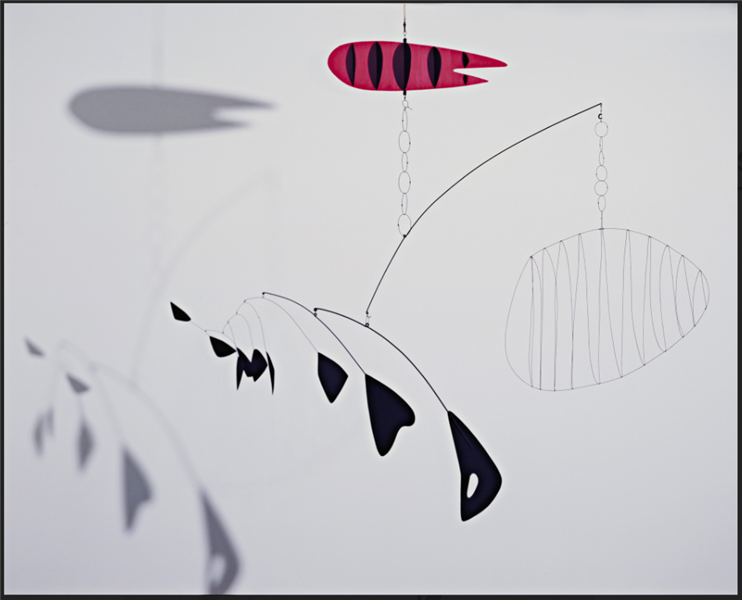

Alexander Calder, Lobster Trap and Fish Tail

If you had a mobile over your crib as a child, you have Alexander Calder to thank for it.

The son and grandson of sculptors, Alexander Calder (1898-1976) initially studied mechanical engineering. Fascinated all his life by motion, he explored movement in relationship to three-dimensional form in much of his work. After a visit to Piet Mondrian’s studio in the early 1930s, Calder set out to put the Dutch painter’s brightly colored rectangular shapes into motion. Marcel Duchamp, intrigued by Calder’s early motorized and hand-cranked examples of moving abstract pieces, names them mobiles. Calder soon used his engineering skills to fashion a series of balanced structures hanging from rods, wires, and colorful, organically shaped plates. This new kind of sculpture, which combined non-objective forms and motion, succeeded in expressing the innate dynamism of the natural world.

An early mobile is Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, which the artist created in 1939 under a commission from the Museum of Modern Art in New York City for the stairwell of the museum’s new building on West 53rd Street. Calder carefully planned each nonmechanized mobile so that any air current would set the parts moving to create a constantly shifting dance in space. Mondrian’s work may have provided the initial inspiration for the mobiles, but their organic shapes resemble those in Joan Miró’s Surrealist paintings. Indeed, viewers can read Calder’s forms as either geometric or organic. Geometrically, the lines suggest circuitry and rigging, and the shapes derive from circles and ovoid forms. Organically, the lines suggest nerve axons, and the shapes resemble cells, leaves, fins, wings, and other bioforms.[1]

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 824. ↵