Duccio, Maesta

The works of Duccio di Buoninsenga (active c. 1278-1318) are the supreme examples of fourteenth-century Sienese art. His most famous commission, the immense altarpiece called the Maestà (Virgin Enthroned in Majesty) replaced a much smaller painting of the Virgin Mary on the high altar of Siena Cathedral. The Sienese believed that the Virgin had brought them victory over the Florentines at the battle of Monteperti in 1260, and she was the focus of the religious life of the republic. Duccio and his assistants began work on the prestigious commission in 1308 and completed the altarpiece in 1311, causing the entire city to celebrate. Shops closed, and the bishop led a great procession of priests, civic officials, and the populace at large in carrying the altarpiece from Duccio’s studio outside the city gate through Siena’s main piazza, or plaza, past the town hall, and up to its home on Siena’s highest hill.

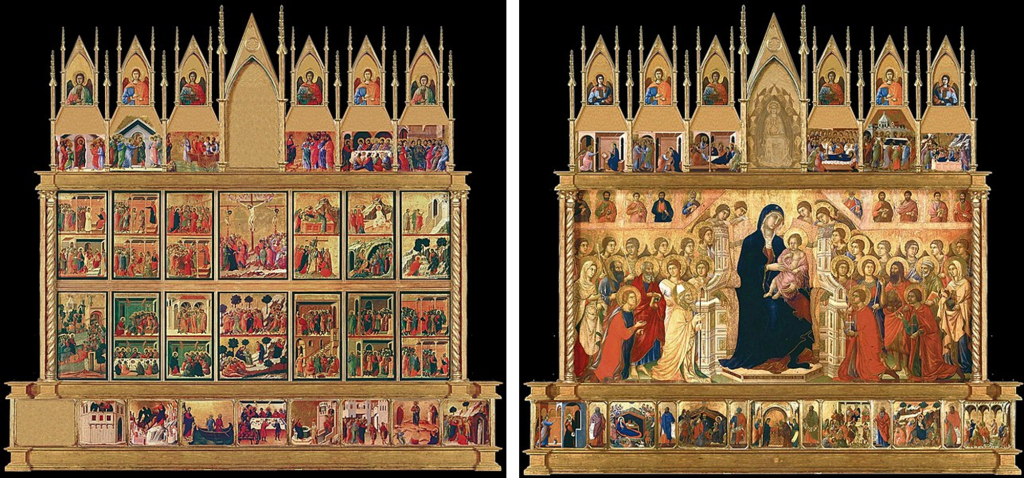

As originally executed, Duccio’s Maestà consisted of the seven-foot-high central panel with the dedicatory inscription, surmounted by seven pinnacles above and a predella, or raised shelf, of panels at the base, altogether some 13 feet high. Painted in tempera front and back, the work unfortunately can no longer be seen in its entirety because of its dismantling in subsequent centuries. Many of Duccio’s panels are on display today as single masterpieces, scattered among the world’s museums.

The main panel on the front of the altarpiece represents the Virgin enthroned as queen of Heaven amid choruses of angels and saints. Duccio derived the composition’s formality and symmetry along with the figures and facial types of the principal angels and saints, from Byzantine tradition. But the artist relaxed the strict frontality and rigidity of the figures. They turn to each other in quiet conversation. Further, Duccio individualized the faces of the four patron saints of Siena (Ansanus, Savinus, Crescentius, and Victor) kneeling in the foreground, who perform their ceremonial gestures without stiffness. Similarly, he softened the usual Byzantine hard body outlines and drapery patterning. The folds of the garments, particularly those of the female saints at both ends of the panel, fall and curve loosely. This is a feature familiar in French Gothic works and is a mark of the artistic dialogue between Italy and northern Europe in the fourteenth century.

Duccio created the glistening and shimmering effects of textiles, adapting the motifs and design patterns of exotic materials Complementing the sumptuous fabrics and the (lost) gilded wood frame are the halos of the holy figures which feature tooled decorative designs in gold leaf (punchwork). But, as did Giotto in his Ognissanti Madonna, Duccio eliminated almost all the gold patterning of the figures’ garments in favor of creating three-dimensional volume. Traces remain only in the Virgin’s red dress.

On the front panel, Duccio showed himself as the great master of the traditional altarpiece. However, in the small accompanying panels front and back, he allowed himself greater latitude for experimentation. (Worshipers could always view both sides because the high altar stood in the center of the sanctuary.) The New Testament scenes on the back of the altarpiece reveal Duccio’s powers as a narrative painter.

In Betrayal of Jesus, for example, the artist represented several episodes of the event – the betrayal of Jesus by Judas’s false kiss, the disciples feeing in terror, and Peter cutting off the ear of the high priest’s servant. Although the background with its golden sky and rock formations remains traditional, the style of the figures before it has changed radically. The bodies are not the flat frontal shapes of Italo-Byzantine art. Duccio imbued them with mass, modeled them with a range of tonalities from light to dark, and arranged their draperies around them convincingly. Even more novel and striking is the way the figures seem to react to the central event. Through posture, gesture, and even facial expression, they display a variety of emotions. Duccio carefully differentiated among the anger of Peter, the malice of Judas (echoed in the faces of the throng about Jesus), and the apprehension and timidity of the feeling disciples. These figures are actors in a religious drama that the artist interpreted in terms of thoroughly human actions and reactions. In this and the other narrative panels, Duccio took a decisive step toward the humanization of religious subject matter.[1]

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 421-423. ↵