Suprematism

Dada was a movement born of pessimism and cynicism. However, not all early-twentieth-century artists reacted to the profound turmoil of the times by retreating from society. Some artists promoted utopian ideals, believing staunchly in art’s ability to contribute to improving society and all humankind. These efforts often surfaced in the face of significant political upheaval, as was the case with Suprematism and Constructivism in Russia.

One Russian artist who contributed significantly to the avant-garde nature of early-twentieth-century art was Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935). Malevich developed an abstract style to convey his belief that the supreme reality in the world is “pure feeling,” which attaches to no object. Thus this belief called for new, nonobjective forms in art – shapes not related to objects in the visible world. Malevich had studied painting, sculpture, and architecture and had worked his way through most of the avant-garde styles of his youth before deciding that none could express pure feeling. He christened his new artistic approach Suprematism, explaining: “Under Suprematism I understand the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.”

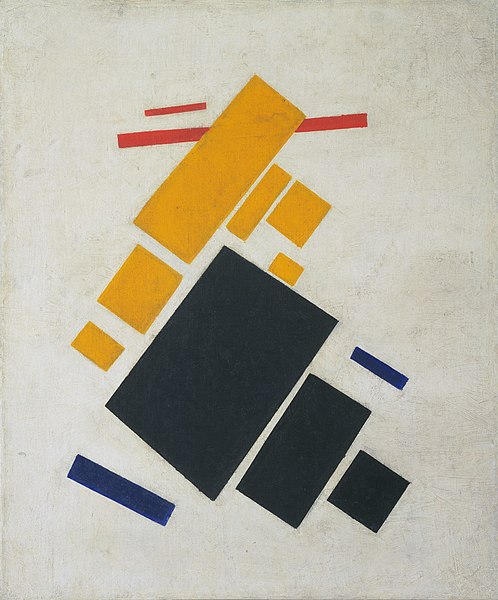

The basic form of Malevich’s new Suprematist nonobjective art was the square. Combined with its relatives, the straight line and the rectangle, the square soon filled his paintings, such as Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying. In this work, the brightly colored shapes float against and within a white space, and the artist placed them in dynamic relationships to one another. Malevich believed that all peoples would easily understand his new art because of the universality of its symbols. It used the pure language of shape and color, to which everyone could respond intuitively.[1]

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 783. ↵