Form and meaning

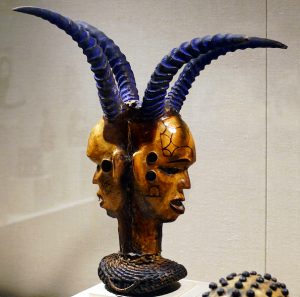

Realism or physical resemblance is generally not the goal of the African artist. Many forms of African art are characterized by their visual abstraction, or departure from representational accuracy. Artists interpret human or animal forms creatively through innovative form and composition. The degree of abstraction can range from idealized naturalism, as in the cast brass heads of Benin kings (below, left), to more simplified, geometrically conceived forms, as in the Baga headdress (below).

The decision to create abstract representations is a conscious one, evidenced by the technical ability of African artists to create naturalistic art, as seen, for example, in the art of Ife, in present-day Nigeria. Idealization is frequently seen in representations of human beings. Individuals are almost always depicted in the prime of life, never in old age or poor health. Culturally accepted standards of moral character and physical beauty are expressed through formal emphasis.

Masks used by the women’s Sande society, for example, present Mende cultural ideals of female beauty. Instead of a physical likeness, the artist highlights admired features, such as narrow eyes, a small mouth, carefully braided hair, and a ringed neck. Idealized images often relate to expected social roles and emphasize distinctions between male and female.

In Bamana statuary, full breasts and a swelling belly highlight a woman’s role as nurturer (left). At the same time, complementary male and female pairs of figures express the concept of an ideal social unit through matched gestures, stances, and expressions.

Form and Meaning

While creations by African artists have been admired by Western viewers for their formal power and beauty, it is important to understand these artifacts on their own terms. Many African artworks were (and continue to be) created to serve a social, religious, or political function. In its original setting, an artifact may have different uses and embody a variety of meanings. These uses may change over time. A mask originally created for a particular performance may be used in a different context at a later time. Nwantantay masks, used by the southern Bwa in Burkina Faso, may be performed during burial ceremonies and also for annual renewal rites. Artworks can also have different meanings for different individuals or groups. A sculpture owned by an elite association holds deeper levels of meaning for its members than for the general public, who may understand only its basic meaning. The painted designs on an Ejagham headdress, for example, represent an indigenous form of writing, the meanings of which are restricted to individuals of the highest status and rank. Understanding the cultural contexts and symbolic meanings of African art therefore enhances our appreciation of its form.[1]

- Dr. Christa Clarke, "Form and meaning," in Smarthistory, October 9, 2016, https://smarthistory.org/form-and-meaning/ ↵