Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and the Forbidden City

After nearly a hundred years of Mongol rule, China returned to native rulership in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The Ming was founded by a commoner, Zhu Yuanzhang (1328–1398), who established Nanjing as his capital. However, nearly fifty years later, the third Ming emperor relocated the capital to Beijing, which has remained China’s main seat of government ever since. The Ming dynasty’s almost three hundred-year span witnessed unprecedented economic and cultural expansion and the near doubling of its population. The last century of the Ming, however, was besieged by border troubles, crop failure, fiscal instability, and court corruption leading to an overthrow by Manchu invaders from the north, who took Beijing in 1644.

Notable Ming achievements include the refurbishment of the Great Wall to its greatest glory, large naval expeditions, vibrant maritime trade, and the rise of a heavily monetized economy. Vital cultural achievements included the production of exceptional—and often colorful—porcelains, paintings, lacquers, and textiles, which created a dazzling visual world. The rise of the novel as a popular literary genre, accompanied by affordable illustrated books, brought literature to many. As a result of cultural achievements and economic achievements, the Ming saw a larger consumer base for luxury goods than any earlier period.

In south China in Jingdezhen, kiln workshops during the Yuan dynasty had already produced large amounts of porcelain, but the city’s position as the main ceramic supplier for both domestic and foreign markets was solidified during the Ming. Judging from its broad distribution, Ming “blue-and-white” porcelain (white body decorated with cobalt-blue painting under the glaze) was the dominant ceramic ware around the globe. [1]

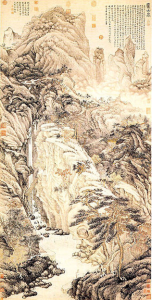

As under the Yuan emperors, Ming literati practiced their art largely independently of court patronage. One of the leading figures was Shen Zhou (1427–1509). Lofty Mount Lu, perhaps Shen’s finest hanging scroll, was a birthday gift to one of his teachers. It bears a long poem that the artist composed in the teacher’s honor. Shen had never seen Mount Lu, but he stated that he chose the subject because he wished the lofty mountain peaks to express the grandeur of his teacher’s virtue and character. The literati master suggested the immense scale of Mount Lu by placing a tiny figure at the bottom center of the painting, sketched in lightly and partly obscured by a rocky outcropping. Characteristic of literati painting in general, the scroll is in the end a very personal conversation—in pictures and words—between the artist and the teacher it honors.

Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 1, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2010), 1064.

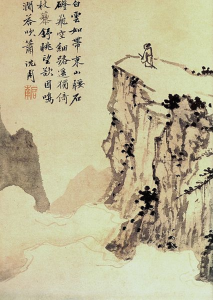

In Poet on a Mountaintop, the poet has climbed the mountain and dominates the landscape. Even the clouds are beneath him. Before his gaze, a poem hangs in the air, as though he were projecting his thoughts.

The poem, composed by Shen Zhou himself, and written in his distinctive hand, reads:

White clouds like a scarf enfold the mountain’s waist,

Stone steps hang in space – a long, narrow, path,

Alone, leaning on my cane, I gaze intently at the scene,

And feel like answering the murmuring brook with the music of my flute.

(Translation by Jonathan Chaves, The Chinese Painter as Poet, New York, 2000, 46.)

Shen Zhou composed the poem and wrote the inscription at the time that he painted the album. The style of calligraphy, like the style of the painting, is informal, relaxed, and straightforward – qualities that were believed to reflect the artist’s character and personality.

The painting visualizes Ming philosophy which held that the mind, not the physical world, was the basis for reality. With its tight synthesis of poetry, calligraphy, and painting, and with its harmony of mind and landscape, Poet on a Mountaintop represents the essence of Ming literati painting.[2]

The Forbidden City

The Forbidden City is a large precinct of red walls and yellow glazed roof tiles located in the heart of China’s capital, Beijing. As its name suggests, the precinct is a micro-city in its own right. Measuring 961 meters in length and 753 meters in width, the Forbidden City is composed of more than 90 palace compounds including 98 buildings and surrounded by a moat as wide as 52 meters.

The Forbidden City was the political and ritual center of China for over 500 years. After its completion in 1420, the Forbidden City was home to 24 emperors, their families and servants during the Ming (1368–1644) and the Qing (1644–1911) dynasties. The last occupant (who was also the last emperor of imperial China), Puyi (1906–67), was expelled in 1925 when the precinct was transformed into the Palace Museum. Although it is no longer an imperial precinct, it remains one of the most important cultural heritage sites and the most visited museum in the People’s Republic of China, with an average of eighty thousand visitors every day.

Construction and layout

Since the Forbidden City is a ceremonial, ritual and living space, the architects who designed its layout followed the ideal cosmic order in Confucian ideology that had held Chinese social structure together for centuries. This layout ensured that all activities within this micro-city were conducted in the manner appropriate to the participants’ social and familial roles. All activities, such as imperial court ceremonies or life-cycle rituals, would take place in sophisticated palaces depending on the events’ characteristics. Similarly, the court determined the occupants of the Forbidden City strictly according to their positions in the imperial family.

Public and private life

Public and domestic spheres are clearly divided in the Forbidden City. The southern half, or the outer court, contains spectacular palace compounds of supra-human scale. This outer court belonged to the realm of state affairs, and only men had access to its spaces. It included the emperor’s formal reception halls, places for religious rituals and state ceremonies, and also the Meridian Gate (Wumen) located at the south end of the central axis that served as the main entrance.

Upon passing the Meridian Gate, one immediately enters an immense courtyard paved with white marble stones in front of the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihedian). Since the Ming dynasty, officials gathered in front of the Meridian Gate before 3 a.m., waiting for the emperor’s reception to start at 5 a.m.

While the outer court is reserved for men, the inner court is the domestic space, dedicated to the imperial family. The inner court includes the palaces in the northern part of the Forbidden City. Here, three of the most important palaces align with the city’s central axis: the emperor’s residence known as the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqinggong) is located to the south while the empress’s residence, the Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunninggong), is to the north. The Hall of Celestial and Terrestrial Union (Jiaotaidian), a smaller square building for imperial weddings and familial ceremonies, is sandwiched in between.

Although the Palace of Heavenly Purity was a grand palace building symbolizing the emperor’s supreme status, it was too large for conducting private activities comfortably. Therefore, after the early 18th century Qing emperor, Yongzheng, moved his residence to the smaller Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxindian) to the west of the main axis, the Palace of Heavenly Purity became a space for ceremonial use and all subsequent emperors resided in the Hall of Mental Cultivation.

The eastern and western sides of the inner court were reserved for the retired emperor and empress dowager. In addition to these palace compounds for the older generation, there are also structures for the imperial family’s religious activities in the east and west sides of the inner court, such as Buddhist and Daoist temples built during the Ming dynasty.[3]

Shen Zhou

- National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, "Ming dynasty (1368–1644), an introduction," in Smarthistory, April 23, 2021, accessed March 21, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/ming-dynasty-intro/. ↵

- Marilyn Stokstad, Art History, vol. 2, 4th ed, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall: 2011), 803. ↵

- Dr. Ying-chen Peng, "The Forbidden City," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed March 21, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/the-forbidden-city ↵