Virgin of Guadalupe

Loving mother. Devoted wife. Ideal woman. Queen of Heaven.

Who could ever be this perfect? For Christians, the Virgin Mary carries all these titles, and she is often celebrated in art as a mother, wife, and queen. With Spanish colonization of the Americas, devotion to the Virgin Mary crossed the Atlantic.

The conquistador Hernán Cortés even carried a small statue of the Madonna with him as he searched for gold and encountered the Indigenous peoples of Mexico. After the defeat of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521 and the establishment of the Spanish Viceroyalty of New Spain (Spanish rule in Mexico, Central America, and part of the U.S., 1521–1821), the Virgin Mary became one of the most popular themes for artists. One Marian cult image eventually became more popular than any other however: the Virgin of Guadalupe, also known as La Guadalupana. Her image is found everywhere throughout Mexico today, gracing churches, chapels, homes, restaurants, vehicles, and even bicycles.

Imagery from the Book of Revelation and the Song of Songs

Many people consider the original image of Guadalupe to be an acheiropoieta, or a work not made by human hands, and so divinely created. Some consider the image the product of an Indigenous artist named Marcos Cipac (de Aquino), working in the 1550s. In the original image, still enshrined in the basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City today, Guadalupe averts her gaze and clasps her hands together in piety. She stands on a crescent moon, and is partially supported by a seraph (holy winged-being) below. She wears Mary’s traditional colors, including a brilliant blue cloak over her dress. Embroidered roses decorate her rose-colored dress. Golden stars adorn her cloak and a mandorla of light surrounds her.

The image of Guadalupe relates to Immaculate Conception imagery, which drew aspects of its symbolism from the Book of Revelation and the Song of Songs. For instance, the Book of Revelation describes the Woman of the Apocalypse as “clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.” In the Guadalupe image, twelve golden rays frame her face and head, a direct reference to the crown of stars.

Her miraculous revelation to Juan Diego

The story associated with her miraculous revelation varies depending on the author, but the general story goes something like this: In December 1531, a converted Nahua man named Juan Diego was on his way to mass. As he walked on the hill of Tepeyac(ac), formerly the site of a shrine to the Aztec mother goddess Tonantzin, Guadalupe appeared to him as an apparition, calling him by name in Nahuatl, the language of the Nahua. According to one textual account written in Nahuatl, Juan Diego described her as dark-skinned, with “Garments as brilliant as the sun.” She requested that Juan Diego ask the bishop, Juan de Zumárraga, to construct a shrine in her honor on the hill. After recounting the story, the bishop did not believe Juan Diego and requested proof of this miraculous appearance. After speaking again with Guadalupe on two other occasions, she informed Juan Diego to gather Castilian roses—growing on the hillside out of season—inside his tilma, or native cloak made of maguey fibers, and bring them to the bishop. When Juan Diego opened his tilma before Bishop Zumárraga the roses spilled out and a miraculous imprint of Guadalupe appeared on it. Immediately, Bishop Zumárraga began construction of a shrine on the hill.

Devotion to Guadalupe

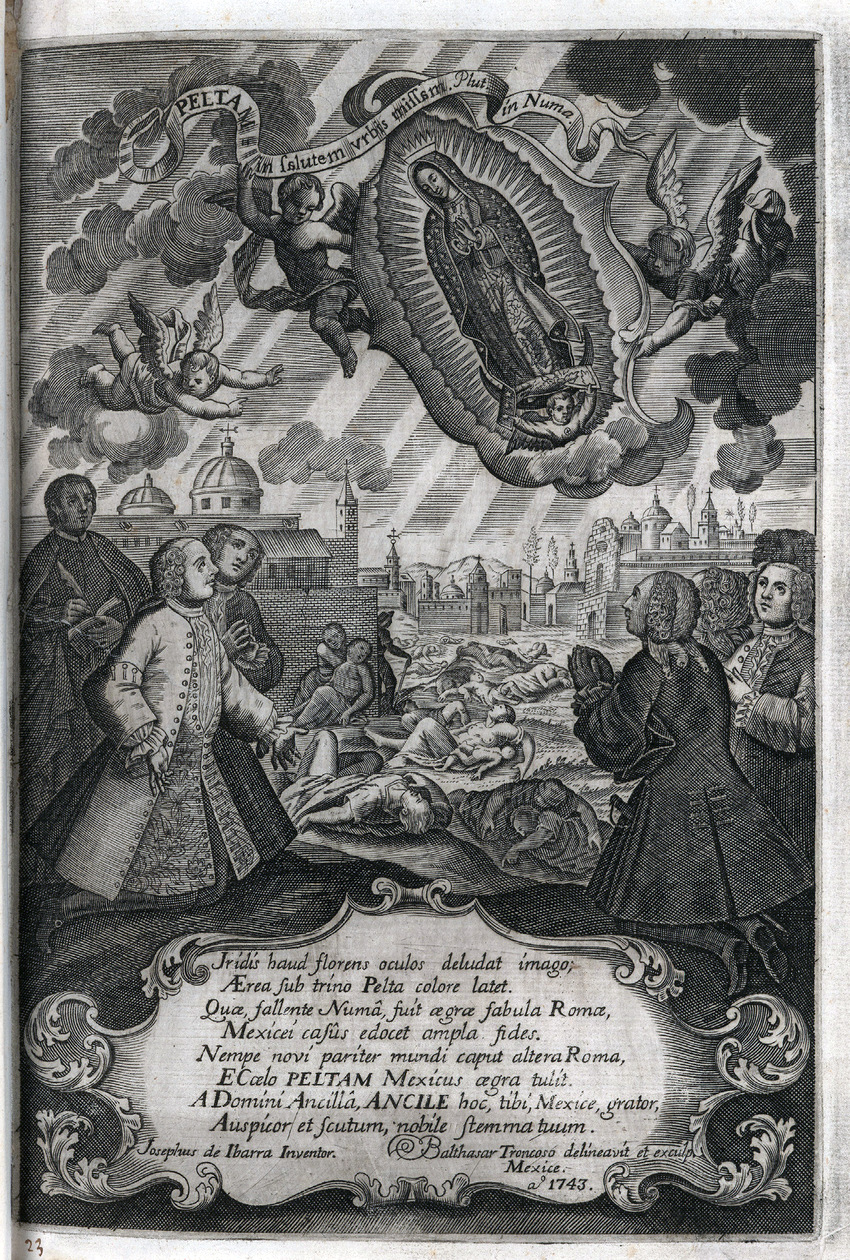

Initially, devotion to Guadalupe was primarily local. Yet veneration of Guadalupe increased, especially because people attributed her with miraculously interceding on their behalf during calamitous events. For instance, she was thought to assist in ending a flood in Mexico City in 1629 and an epidemic that ravaged the population of the capital between 1736–37. After the 1737 epidemic subsided, Mexico City declared her patron of the city. In 1746, Guadalupe was even declared the co-patroness of New Spain along with St. Joseph, and Pope Benedict XIV granted a feast day and mass in her honor for December 12 in the year 1754.

She was so revered that people of different social and ethnic backgrounds paid her reverence. In particular, criollos (or creoles, pure-blooded Spaniards born in the Americas) promoted her devotional cult. They wrote some of the earliest texts recounting her miraculous appearance on Novohispanic soil, a fact they advertised as proof that God blessed the Americas and approved of a new nation. To support this notion, artists often included the motto “Non fecit taliter omni nationi” (Psalm 147:20—He has not dealt thus with any other nation) into their artworks.

True copies

Images depicting Guadalupe proliferated in the seventeenth century as devotion to her increased. Prints, paintings, and enconchados (oil painting and shell-inlay) replicate the original tilma image. Sometimes artists included inscriptions that mention the representation is a true copy of the tilma image.

For example, Manuel de Arellano writes “After the original” (Tocada el original) on his 1691 version of Guadalupe. This statement suggests that artists based their work on the original image and some of the power of the original image transferred to the replication. Besides replicating the tilma image, artists often included the narrative of the miracle in the four corners of the composition, as Arellano’s and Isidro Escamilla’s version from 1824 demonstrate. Frequently flowers frame the mandorla surrounding Guadalupe, a direct reference to the Castilian roses in Juan Diego’s tilma.

To prove further that New Spain was equal to Europe, some of the most famous artists of the eighteenth century, such as Miguel Cabrera and Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, were invited by the clergymen of the Basilica of Guadalupe to inspect the image on April 30, 1751 to authenticate that the image was indeed miraculous. In 1756, Cabrera published the result of this inspection as Maravilla Americana (American Marvel) in which he declared that the tilma image was indeed an acheiropoieta.[1]

- Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, "Virgin of Guadalupe," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/virgin-of-guadalupe/. ↵