The role of the workshop in late medieval and early modern northern Europe

The kitchen metaphor

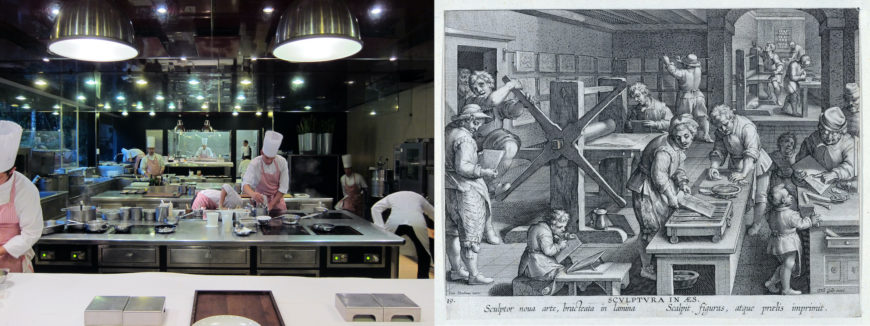

We may think of an individually named artist as the lone maker of a work of art, but workshop assistants played a vital part in artistic production in fifteenth-century northern Europe. The artistic workshop operated a lot like today’s fine dining restaurant kitchen. The executive chef oversees the kitchen and hierarchically organizes the space depending on task and skill level. Even though the executive chef designed the restaurant’s theme and the menu, his/her hand played little part in actually cooking each dish during service.

Cooperative learning and collaboration

Late-medieval and early modern northern European workshops operated on the principles of cooperative learning and collaboration. Like the workshop in Italian Renaissance art, late-medieval and early modern northern European workshops also operated on the principles of cooperative learning and collaboration.

Both large and small workshops functioned hierarchically with centralized management and divided labor based on technical expertise and training experience. The head of the workshop was called a master. In Antwerp around the year 1500, it could take 11 years to become a master. Masters were also allowed to sell their works of art at the guild’s booth by the Antwerp Cathedral.

The typical workshop master employed assistants as apprentices or journeymen. An apprentice is like a master-in-training. To return to the kitchen metaphor, a stage or internship is the cornerstone of chef training: young chefs study under executive chefs to gain practical experience in the kitchen before advancing to the next career stage. In the workshop, an apprentice assisted the master closely to learn the trade. In contrast, journeymen were itinerant artists. They required less hands-on training than assistants, and could travel far from their home city in search for temporary work and were often brought in for specific commissions. Not every master had assistants, but on average, the more costly a commission, the more likely the master had extra sets of hands.

Knowledge of how these assistants were trained remains highly speculative, yet it is clear that training depended on the ability to emulate and repeat the master’s work. In the fifteenth century, workshop masters required a cohesive style: collaborators and assistants had to imitate the master.

Training was often done within families, where young artisans had easy access to learning and tools of the trade. In particular, goldsmithing and metalworking—gouging fine lines into a metal—served as a gateway to early printmaking. For instance, the highly skilled early engraver, Martin Schongauer clearly translated his familial training in goldsmithing to the metal plate. Albrecht Dürer began his training as a draftsman in his father’s goldsmith workshop as well. Dürer’s mother, Barbara, and wife, Agnes, are recorded selling his prints at local fairs and abroad.

Guilds and the rise of the ‘artist’

Masters in later medieval urban centers belonged to guilds. Cities like Bruges and Antwerp, which boasted robust market economies, maintained several guilds according to occupation or a specific trade, such as painting, carpentry, or goldsmithing. Guilds served a variety of practical functions: they offered education and training, regulation, conflict management, as well as professional solidarity.

The Guild of St. Luke was the most common name of painters guilds, although in many cities the Guild of St. Luke also encompassed sculptors and other arts. The name derives from St. Luke the Evangelist, the patron saint of artists, who according to legend, painted an icon of the Virgin.

Guilds became one of the foundational aspects of art-making in the late-medieval city. As a leading artistic center in northern Europe, Bruges was home to some of the most well-known painters in the fifteenth century, including Jan van Eyck, Petrus Christus, and Hans Memling, among others. In Bruges, the painters’ guild applied to all ‘painting’ independent of the type of surface one painted on—wood, cloth, walls, houses, glass, etc. Painters were required to enroll in the guild, in which local citizenship was a prerequisite (citizenship served as a protect against outside competition).[1]

- Dr. Laura Tillery, "The role of the workshop in late medieval and early modern northern Europe," in Smarthistory, August 15, 2021, accessed February 16, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/workshop-northern-europe/ ↵