Hans Holbein, The Ambassadors

One of the most famous portraits of the Renaissance is without question Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors from 1533. Even today, it is a favored portrait to parody, mimic, or cite in art, TV, film, and social media, and it remains an important source for contemporary artists.

This double portrait depicts two men standing beside a high table covered in objects. On the left is Jean de Dinteville, age 29, a French ambassador sent by the French king, Francis I to the English court of Henry VIII. On the right is Georges de Selve, age 25, the bishop of Lavaur, France. They stand on an elaborate abstract pavement, which has been identified as belonging to the sanctuary in Westminster Abbey—the same space where Anne Boylen, second wife of Henry VIII, had been crowned and more recently, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge were married.

The painting is filled with carefully rendered details, in a clear style that we have come to identify with Renaissance naturalism of the sixteenth century. The anamorphic skull in the foreground continues to delight and surprise viewers, and to inspire artists.

Draped over the top level of the table between the two men is a carpet, usually referred to as a “Holbein Carpet” because of the artist’s fondness for painting this type of textile. This name, though, would not have been used in the sixteenth century. Instead, the carpet would have reminded observers of the place from where it was produced—in this case Turkey—which was controlled, in the sixteenth century, by the Ottomans. Anatolian carpets were popular luxury objects in Europe from the fifteenth century onward. Textiles from Turkey, as well as other parts of the eastern Mediterranean were highly sought after because of their extraordinary craftsmanship and beauty.

Carpets like the one in Holbein’s painting were expensive. They figured prominently in elite European homes, and often cost as much as paintings and sculptures. Unlike today, a carpet of such expense would not be placed on the floor. It would be draped over a table, as shown in The Ambassadors, to be displayed as a beautiful object to observe and delight in.

So why is a carpet in Holbein’s painting? The carpet is a luxury object meant to elevate the two men’s status. It also reminds us of the power and prestige of the Ottoman Empire at the time. The Ottomans were considered a threat to the European powers, even as Europeans desired Ottoman luxuries, such as carpets.

Objects on the shelf

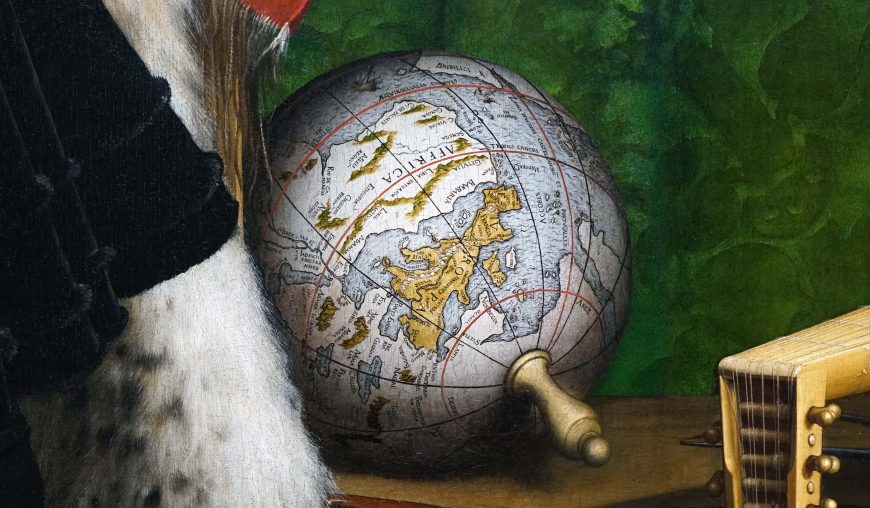

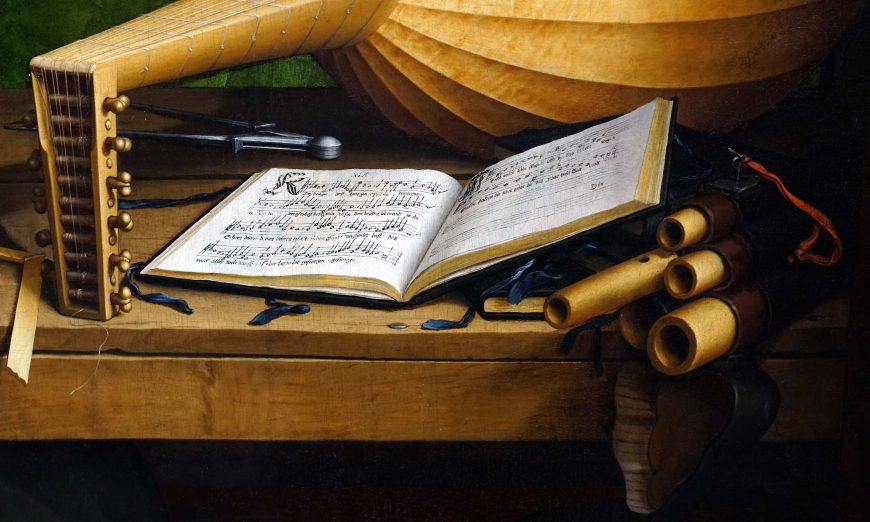

On the shelf below the carpet, there are a number of intriguing objects, including a lute with a broken string, a hymn book, and a globe. The lute’s broken string is thought to reference the discord that resulted from the Protestant Reformation, which the hymn book also calls to mind. Martin Luther, who initiated the Reformation, composed the hymns shown.

The globe, however, does not refer to the upheaval that resulted from the Reformation, but it does call to mind other types of transformations then taking place. Interestingly, one of the legible inscriptions on the globe is “Brisillici R.” for Brazil. The visual clarity and reference to Brazil is important. The French crown made a claim to Brazil after it had sponsored an expedition to the Americas in 1522. Heading the expedition was Giovanni da Verrazano, who returned in 1524, helping France to stake a claim to lands across the Atlantic. Verrazano would return to Brazil in 1527 to collect Brazilwood, a valuable resource. The French crown attempted to establish trading posts in Brazil in order to claim control over this rich foreign land, an action that pit France against its colonial rival Portugal.

Like the globe and the Turkish carpet, the book that rests on the table just in front of the globe also alludes to the importance of trade. Holbein’s precise manner of painting the book allows us to identify it as an arithmetic text, specifically the German astronomer Peter Apian’s A New and Well-grounded Instruction in All Merchants’ Arithmetic (Eyn Newe unnd wolgegruündte underweysun aller Kauffmannss Rechnung). The book discusses profits and losses—an important aspect of mercantilism and trade in this period. The navigational instruments on the upper shelf also point to commercial activities that sponsored travel and exchange, but also imperialist expansion and colonization. Each is an important theme in this complex painting.[1]

- Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, "The carpet and the globe: Holbein’s The Ambassadors reframed," in Smarthistory, October 30, 2020, accessed March 31, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/hans-holbein-the-younger-the-ambassadors/ ↵