Chuck Close and Duane Hanson

Like the Pop artists, the artists associated with Superrealism sought a form of artistic communication more accessible to the public than the remote, unfamiliar visual language of the Abstract Expressionists, Post-Painterly Abstractionists, and Minimalists. The Superrealists expanded Pop’s iconography in both painting and sculpture by making images in the late 1960s and 1970s involving scrupulous fidelity to optical fact. Because many Superrealists used photographs as sources for their imagery, art historians also refer to this postwar art movement as Photorealism.

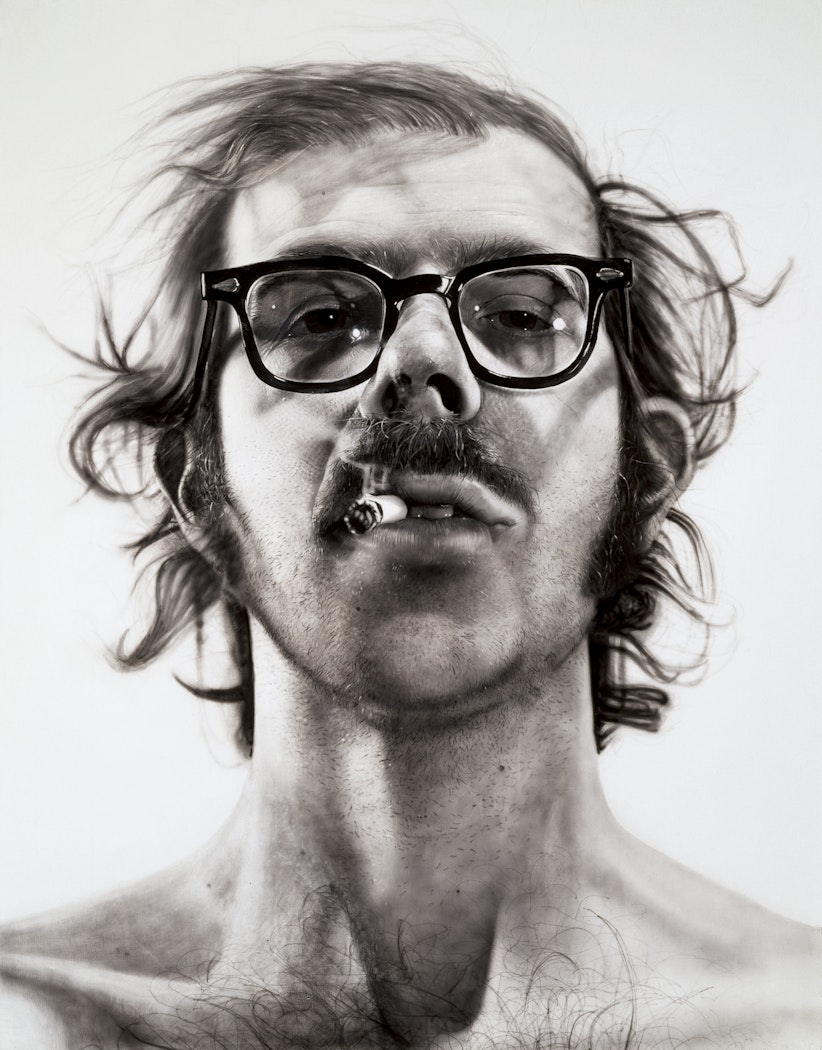

Chuck Close (1940-2021) based his paintings of the late 1960s and early 1970s on photographs, and his main goal was to translate photographic information into painted information. Because he aimed simply to record visual information about his subject’s appearance, Close deliberately avoided creative compositions, flattering lighting effects, and revealing facial expressions. Not interested in providing great insight into the personalities of those portrayed, Close painted anonymous and generic people, mostly friends. Close said of his technique: “To avoid a painterly brush stroke and surface, I use some pretty devious means, such as razor blades, electric drills, and airbrushes. I also work as thinly as possible, and I don’t use white paint as it tends to build up and become chalky and opaque. In fact, in a nine-by-seven-foot picture, I use only a couple of tablespoons of black paint to cover the entire canvas.”

Duane Hanson (1925-1996) spent much of his career in southern Florida. Hanson perfected a casting technique that enabled him to create life-size figurative sculptures that many viewers mistake first for real people. Hanson began by making plaster molds from live models and then filled the molds with polyester resin. After the resin hardened, he removed the outer molds and cleaned, painted with an airbrush, and decorated the sculptures with wigs, clothes, and other accessories. These works (such as Traveler and Museum Guard), depict stereotypical average Americans, striking chords with the public specifically because of their familiarity.

Hanson explained his choice of imagery: “The subject matter that I like best deals with the familiar lower-and middle-class American types of today. To me, the resignation, emptiness and loneliness of their existence captures the true reality of life for these people. . . . I want to achieve a certain tough realism which speaks of the fascinating idiosyncrasies of our time.”[1]

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 851-853. ↵