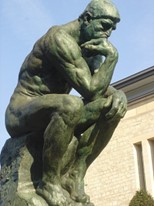

Auguste Rodin, Gates of Hell

The Symbolist desire to penetrate and portray the innermost essence of being had a parallel in the sculpture of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), the most influential sculptor of the late nineteenth century, who single-handedly laid the foundation for twentieth-century sculpture. He was rejected at the École des Beaux-Arts, forcing him to attend the Petit École, which specialized in the decorative arts. His big break came in 1880, when he won a prestigious commission to design the bronze doors for a new decorative arts museum. Although the project eventually fell through, Rodin continued to work on it right up to his death.

Called The Gates of Hell, the 17-foot high doors were inspired by Dante’s Inferno from the Divine Comedy, and at one point the thinker sitting in the tympanum contemplating the ghoulish scene below was to be Dante. Ultimately, the doors became a metaphor for the futility of life, the inability to satisfactorily fulfill our deepest uncontrollable passions, which is the fate of the sinners in Dante’s second circle of hell, the circle that preoccupied Rodin the most. It is the world after the Fall, of eternal suffering, and Adam and Eve are included among the tortured souls below. Despite Rodin’s devotion to the project, the Gates were never cast during his lifetime.

Rodin made independent sculptures from details of the Gates, including The Thinker and The Three Shades, the group mounted at the very peak of the Gates, which shows the same figure merely turned in three positions. While his figures are based on familiar models – The Thinker, for example, recalls the work of Michelangelo, his favorite artist – they have an unfamiliar organic quality. Rodin preferred to mold, not carve, working mostly in plaster or terra cotta, which artisans would then cast in bronze. We see where Rodin’s hand has worked the malleable paster with his fingers, for his surfaces ripple and undulate. For the sake of expression, Rodin does not hesitate to distort his figures, shattering Classical notions of the idealized form and beauty. We can see this distortion in The Thinker. Here, massive hands and feet project a ponderous weight that underscores the thinker’s psychological load, while his elongated arm is draped limply over his knee, suggesting inertia and indecision.[1]

- Penelope J.E. Davies, et. al. Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2007), 927-928. ↵