Raphael, School of Athens

In 1508, the young Raphael left Florence to arrive in Rome as Michelangelo was beginning work on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. He quickly secured a commission from Pope Julius II to paint the pope’s private rooms in the Vatican Palace. The first of these rooms was the so-called Stanza della Segnatura (Room of the Signatures), where subsequent popes signed official documents, but which Julius used as a library. On each of the four walls, Raphael was to paint one of the four major areas of humanist learning: Law and Justice, Poetry, Theology, and Philosophy.

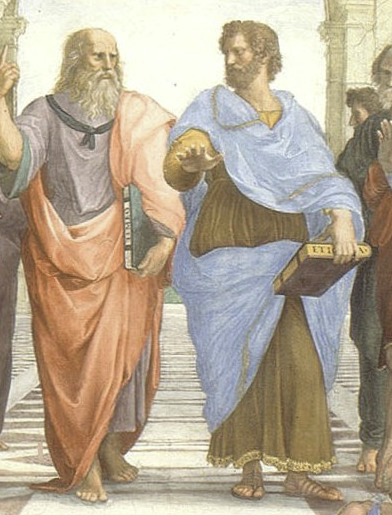

The School of Athens, also known as Philosophy, is generally acknowledged as the most important of Raphael’s four paintings for the Stanza della Segnatura. Its classicism is clearly indicated in several ways: by its illusionistic architectural setting, based on ancient Roman baths; by its emphatic one-point perspective, which directs viewer attention to the two central figures, Plato and Aristotle, fathers of philosophy; and by its subject matter, the philosophical foundation of the Renaissance humanistic enterprise. All of the figures here – the Platonists on the left, the Aristotelians on the right, though not all have been identified – were regarded by Renaissance humanists as embodying the ideal of continual pursuit of learning and truth. The clarity, balance, and symmetry that distinguish the Raphael composition became a touchstone for painters in centuries to come.

Let’s take a closer look at who is represented in this fresco.

Plato (c. 428-348 BCE) (left) resembles a self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci. He points upward to the realm of ideas. He carries the Timaeus, the dialogue on the origin of the universe, in which he argued that the circle is the image of cosmic perfection. Aristotle (384-322 BCE) (right) carries his Nichomachean Ethics and gestures outward toward the earthly world of the viewer, emphasizing his belief in empiricism – that we can only understand the universe through the careful study and examination of the natural world.

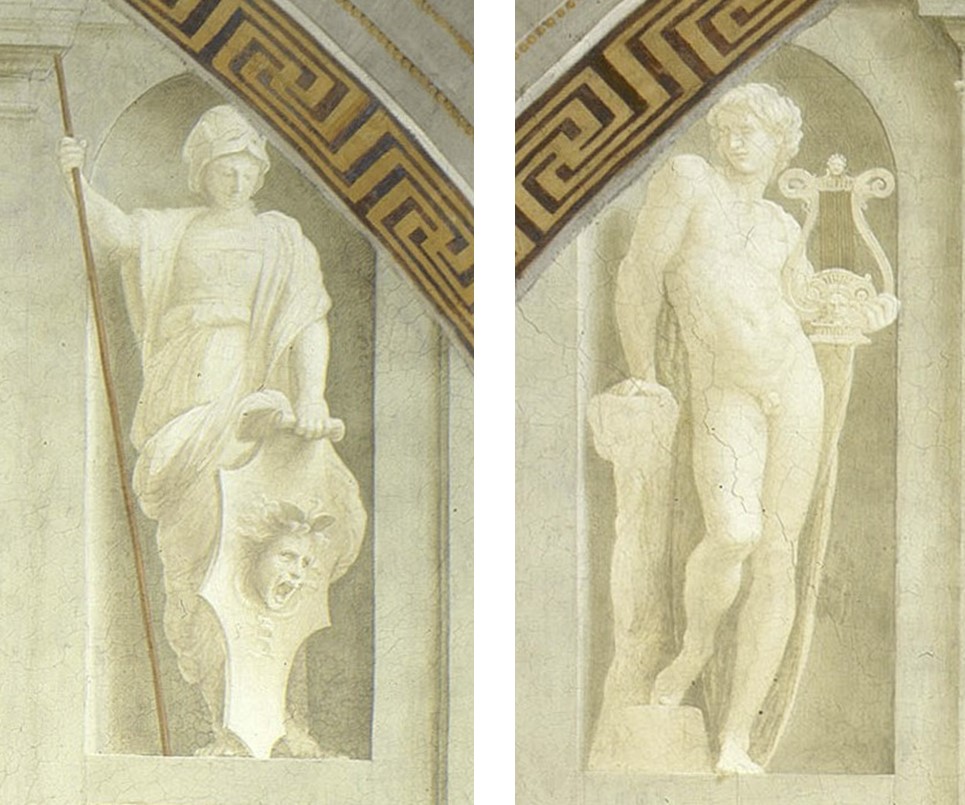

Apollo, holding a lyre, is god of reason, patron of music, and symbol of philosophical enlightenment. Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, is the traditional patron of those devoted to the pursuit of truth and artistic beauty.

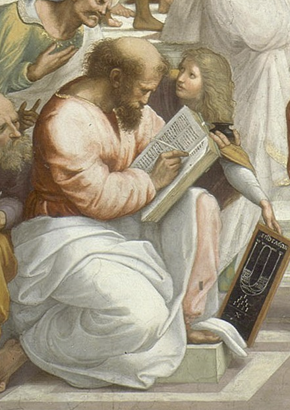

Pythagoras (c. 570-490 BCE) the Greek mathematician, illustrates the theory of proportions to interested students – among them, wearing a turban, the Arabic scholar Averroës (1126-98).

Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) debates with Socrates (c. 469-399 BCE), who makes his points by enumerating them on his fingers.

Euclid (third century BCE), whose Elements remained the standard geometry text down to modern times, is actually a portrait of Donato Bramante. Ptolemy, the second-century astronomer and philosopher, holds a terrestrial globe, while Zoroaster (c 628-551 BCE) faces him holding a celestial globe. Both turn toward a young man who looks directly out at us This is a self-portrait of Raphael.

Heraclitus (c. 535-475 BCE) the brooding Greek philosopher who despaired at human folly, wears stonecutter’s boots and is actually a portrait of Michelangelo.[1]

- Henry Sayre, The Humanities: Culture, Continuity and Change, vol. 2, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2015), 510-513. ↵