Orientalism

Snake charmers, carpet vendors, and veiled women may conjure up ideas of the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia, but they are also partially indebted to Orientalist fantasies. To understand these images, we have to understand the concept of Orientalism, beginning with the word “Orient” itself. In its original medieval usage, the “Orient” referred to the “East,” but whose “East” did this Orient represent? East of where?

We understand now that this designation reflects a Western European view of the “East,” and not necessarily the views of the inhabitants of these areas. We also realize today that the label of the “Orient” hardly captures the wide swath of territory to which it originally referred: the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. These are at once distinct, contrasting, and yet interconnected regions. Scholars often link visual examples of Orientalism alongside the Romantic literature and music of the early nineteenth century, a period of rising imperialism and tourism when Western artists traveled widely to the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia.

We now understand that the world has been interconnected for much longer than we initially acknowledged and we can see elements of Orientalist representation much earlier—for example, in religious objects of the Crusades, or Gentile Bellini’s painting of the Ottoman sultan (ruler) Mehmed II, or in the arabesques (flowing s-shaped ornamental forms) of early modern textiles.

The politics of Orientalism

In his groundbreaking 1978 text Orientalism, the late cultural critic and theorist Edward Saïd argued that a dominant European political ideology created the notion of the Orient in order to subjugate and control it. Saïd explained that the concept embodied distinctions between “East” (the Orient) and “West” (the Occident) precisely so the “West” could control and authorize views of the “East.” For Saïd, this nexus of power and knowledge enabled the “West” to generalize and misrepresent North Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Though his text has itself received considerable criticism, the book nevertheless remains a pioneering intervention. Saïd continues to influence many disciplines of cultural study, including the history of art.

Orientalism: fact or fiction?

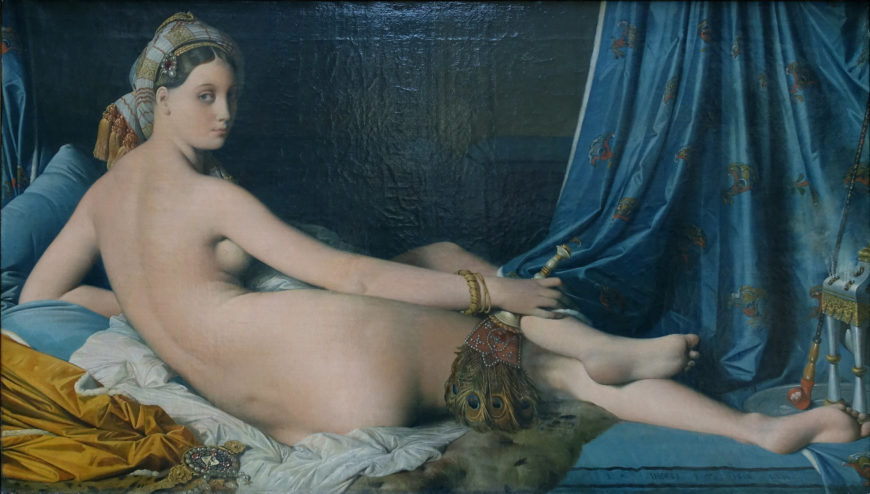

Orientalist paintings and other forms of material culture operate on two registers. First, they depict an “exotic” and therefore racialized, feminized, and often sexualized culture from a distant land. Second, they simultaneously claim to be a document, an authentic glimpse of a location and its inhabitants, as we see with Gérôme’s detailed and naturalistic style. In The Snake Charmer and His Audience, Gérôme constructs this layer of exotic “truth” by including illegible, faux-Arabic tilework in the background. Nochlin pointed out that many of Gérôme’s paintings worked to convince their audiences by carefully mimicking a “preexisting Oriental reality.”[1] In the visual discourses of Orientalism, we must systematically question any claim to objectivity or authenticity.[2]