Masaccio, The Tribute Money and Expulsion in the Brancacci Chapel

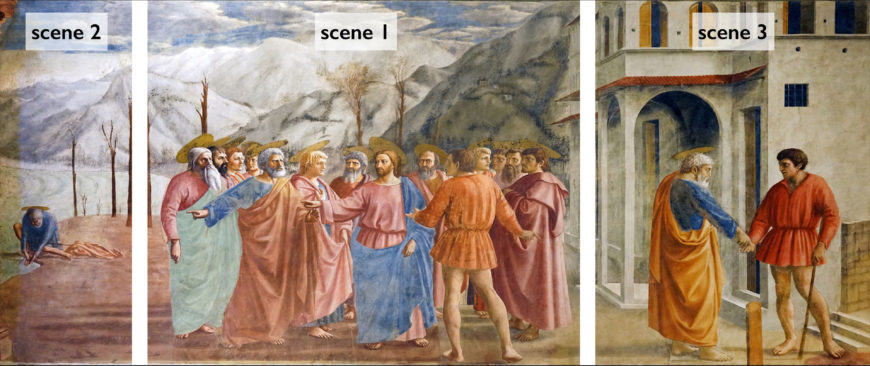

The Tribute Money is one of many frescoes painted by Masaccio (and another artist named Masolino (with later additions by Filippino Lippi) in the Brancacci chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence—when you walk into the chapel, the fresco is on your upper left. All of the frescoes in the chapel tell the story of the life of St. Peter. The story of the Tribute Money is told in three separate scenes within the same fresco. This way of telling an entire story in one painting is called a continuous narrative.

A story unfolds and a miracle is performed

In the Tribute Money, a Roman tax collector (the figure in the foreground in a short orange tunic and no halo) demands tax money from Christ and the twelve apostles who don’t have the money to pay.

Christ (in the center, wearing a pinkish robe gathered in at the waist, with a blue toga-like wrap) points to the left, and says to Peter “so that we may not offend them, go to the lake and throw out your line. Take the first fish you catch; open its mouth and you will find a four-drachma coin. Take it and give it to them for my tax and yours” (Matthew 17:27). Christ performed a miracle—and the apostles have the money to pay the tax collector.

In the center of the fresco (scene 1), we see the tax collector demanding the money, and Christ instructing Peter. On the far left (scene 2), we see Peter kneeling down and retrieving the money from the mouth of a fish, and on the far right (scene 3), St. Peter pays the tax collector. In the fresco, the tax collector appears twice, and St. Peter appears three times (you can find them easily if you look for their clothing).

We are so used to one moment appearing in one frame (think of a comic book, for example) that the unfolding of the story within one image (and out of order!) seems very strange to us. But with this technique (a continuous narrative)—which was also used by the ancient Romans—Masaccio is able to make an entire drama unfold on the wall of the Brancacci chapel.

In the central, first scene, the tax collector points down with his right hand, and holds his left palm open, impatiently insisting on the money from Christ and the apostles. He stands with his back to us, which helps to create an illusion of three dimensional space in the image (a goal which was clearly important to Masaccio as he also employed both linear and atmospheric perspective to create an illusion of space). Like Donatello’s St. Mark from Orsanmichele in Florence, he stands naturally, in contrapposto, with his weight on his left leg, and his right knee bent. The apostles (Christ’s followers) look worried and anxiously watch to see what will happen. St. Peter (wearing a large deep orange colored toga draped over a blue shirt) is confused, as he seems to be questioning Christ and pointing over to the river, but he also looks like he is willing to believe Christ.

The gestures and expressions help to tell the story. Peter seems confused and points to the lake—mirroring Christ’s gesture; the tax collector looks upset, and has his hand out insistently asking for the money—he stands in contrapposto with his back turned to us (contrapposto is a standing position, where the figure’s weight is shifted to one leg). Only Christ is completely calm because he is performing a miracle.

Look down at the feet—how the light travels through the figures, and is stopped when it encounters the figures. The figures cast shadows—Masaccio is perhaps the first artist since classical antiquity to paint cast shadows. What this does is make the fresco so much more real—it is as if the figures are truly standing out in a landscape, with the light coming from one direction, and the sun in the sky, hitting all the figures from the same side and casting shadows on the ground. For the first time since antiquity, there is almost a sense of weather.[1]

- Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, "Masaccio, The Tribute Money and Expulsion in the Brancacci Chapel," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed February 27, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/masaccio-the-tribute-money-in-the-brancacci-chapel/ ↵