Limbourg Brothers, Très Riches Heures

Known collectively as the Limbourg brothers, Paul, Jean and Herman de Limbourg were all highly skilled miniature painters active at the end of the 14th century and the beginning of 15th century. Together, they created some of the most beautiful illuminated books of the Late Gothic period.

The Belles Heures is a Book of Hours— a very popular book to possess during the late medieval period. A Book of Hours is essentially a prayer book (with prayers and readings for set times throughout a day), and it typically featured the “Hours of the Virgin” (a set of psalms with lessons and prayers), a calendar, a standard series of readings from the Gospels, the Office for the Dead, the Penitential Psalms, and hymns (or some variation thereof). They were miniature works of art made for private use, and generally contained a number of intricate illuminations painstakingly created on vellum (calfskin). A book of hours was for personal, devotional use—it was not an official liturgical volume. Typically, these books of hours were quite petite.

The Très Riches Heures

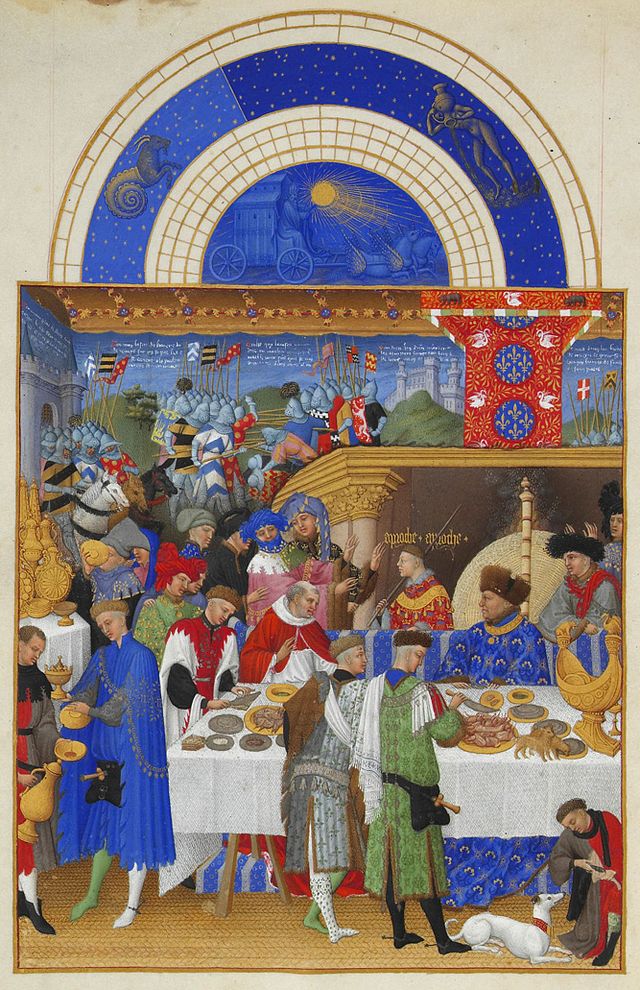

In the Très Riches Heures, there are a number of full-page images—including calendar pages. The calendar pages often show agricultural scenes where happy peasants till the fields and harvest. In the background are castles and landscapes that were specific holdings of the Duke of Berry. Likewise we also see the inside the palace. For example, in January (in full at the top of the page, and detail above) we see an image of the Duke himself, sitting at the head of the table while all around presents are exchanged. Likely, the Limbourgs themselves would have been part of this ritual exchange—the man in the mid-ground with the gray floppy cap may be a self-portrait of Paul. The table, resplendent in damask and laden with expensive goods, represents the wealth and taste of the Duke. A variety of heraldic motifs relating to the Duke can also be found, such as the gold fleur-de-lys (in the blue circles above the Duke for example). In the background we see tapestries with a scene of knights emerging from a castle ready to go into battle.

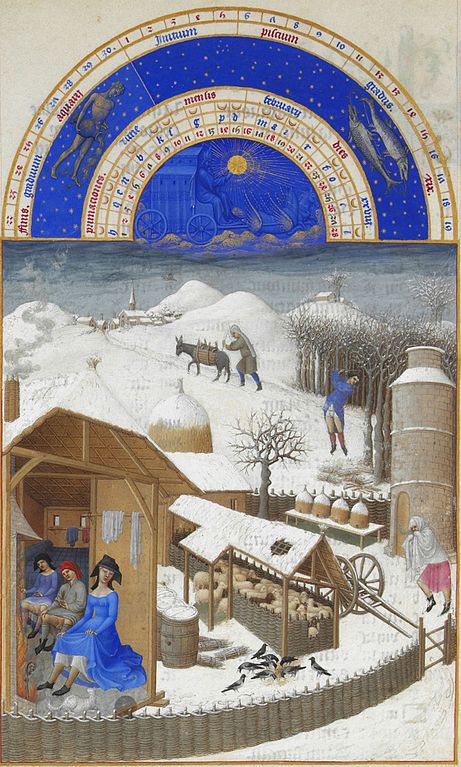

Meanwhile, the February page takes us outside into the frigid winter air. Wan light falls across a snow covered landscape where in the background we see a town blanketed in snow, along with a peasant and a donkey gamely taking the road towards it. In the middle ground we see another peasant diligently chopping wood, while another hurries towards shelter. In the foreground we see the farm as well peasants warming themselves in a small wooden house. he tunics of both the men are pulled so high, assumedly in an effort to warm their chilled legs, that their nether regions are exposed—something that might strike modern viewers as incongruous to a religious book. At least the lady of the house decorously only warms her ankles! However, nudity in medieval manuscripts, while not prolific, was also not unusual. In fact, there are several other examples that can be found in the Très Riches Heures.

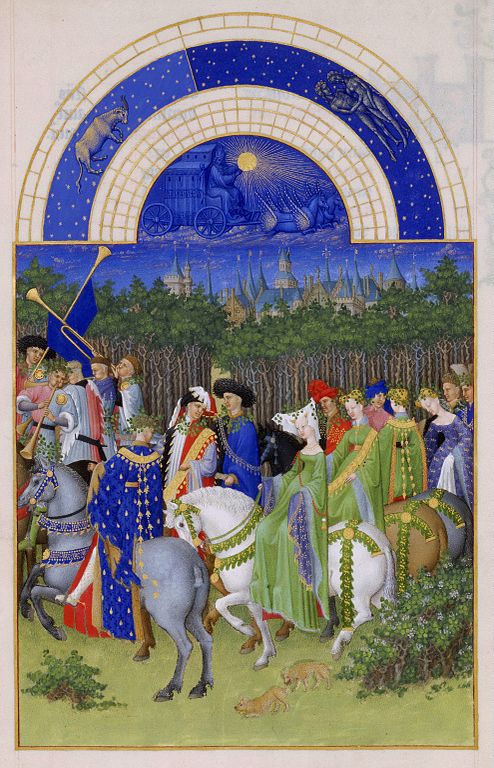

Something else that might strike the modern viewer as curious is the incorporation of the zodiac into this book of hours. For every calendar page, the corresponding astrological sign is shown at the top of the page in a lunette or tympanum. This is in part because the stars were integrally tied to the agricultural calendar. Also, medieval medical practioners believed that people’s health issues were related to what constellation they were born under. Even the church calendar used the Zodiac to calculate feast days. For the month of May (below), we see the astrological signs of the bull and the twins, accompanying the chariot of the sun.

The International Gothic style

The International Gothic style emphasized decorative patterns. This is obvious on the clothing worn by the figures, but even natural forms—like trees—create decorative patterns. Gold leaf, always popular in manuscripts, was also used in abundance. Figures are elegant and elongated. These images are also highly detailed and show an abundant interest in accurately portraying plants and animals. Though the Très Riches Heures, is incomplete, it remains a shining example of the International Gothic style.[1]

- Christine M. Bolli, "Limbourg brothers, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry," in Smarthistory, March 6, 2016, accessed February 21, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/limbourg-brothers-tres-riches-heures-du-duc-de-berry/. ↵