Leonardo’s Last Supper

Leonardo left Florence in 1481 or 1482 for Milan, where he stayed for 20 years. In his letter of application to Duke Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo offered his services, primarily emphasizing his civil and military engineering skills, which included devising bridges, mortars, catapults, and other machines. Only at the end did he casually mention his ability to create sculptures and paintings. The Last Supper was commissioned by Duke Ludovico Sforza for the refectory (room used for communal meals) in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. Leonardo experimented by mixing oil and tempera and applied much of the paint a secco (to dried plaster rather than buon fresco, or wet plaster like Giotto did in the Arena Chapel). Consequently, the wall did not absorb the pigment and the fresco began flaking off soon after completion. A twentieth-century restoration effort (completed in 1999) removed additions of earlier restorers to uncover Leonardo’s original work. Less than half of the surface seen today is original to Leonardo.

Subject

The subject of the Last Supper is Christ’s final meal with his apostles before Judas identifies Christ to the authorities who arrest him. The Last Supper (a Passover Seder) is remembered for two events:

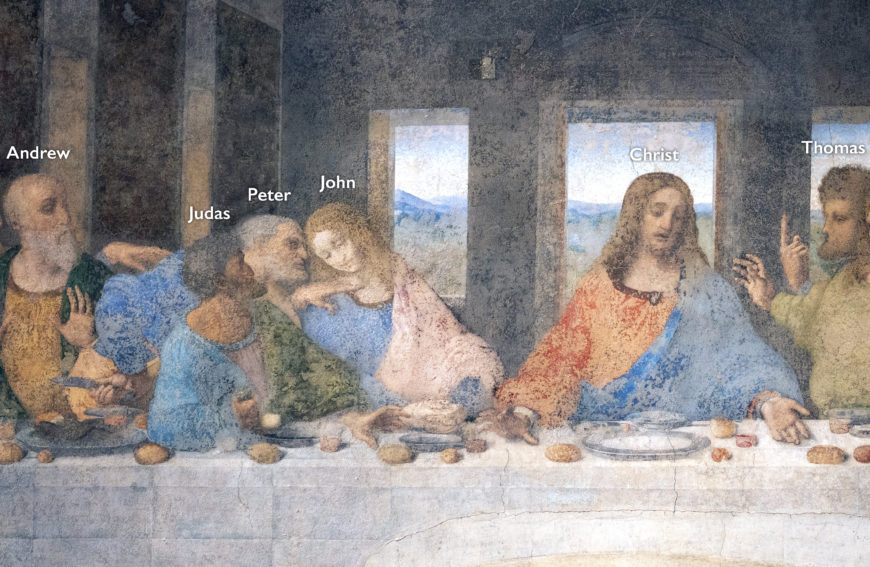

Christ says to his apostles, “One of you will betray me,” and the apostles react, each according to his own personality. Referring to the Gospels, Leonardo depicts Philip asking, “Lord, is it I?” Christ replies, “He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish, the same shall betray me” (Matthew 26). We see Christ and Judas simultaneously reaching toward a plate that lies between them, even as Judas defensively backs away.

Leonardo also simultaneously depicts Christ blessing the bread and saying to the apostles, “Take, eat; this is my body” and blessing the wine and saying “Drink from it all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26). These words are the founding moment of the sacrament of the Eucharist (the miraculous transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ).

Apostles identified

Leonardo’s Last Supper is dense with symbolic references. Attributes identify each apostle. For example, Judas Iscariot is recognized both as he reaches toward a plate beside Christ (Matthew 26) and because he clutches a purse containing his reward for identifying Christ to the authorities the following day. Peter, who sits beside Judas, holds a knife in his right hand, foreshadowing that Peter will sever the ear of a soldier as he attempts to protect Christ from arrest.

Suggestions of the heavenly

The balanced composition is anchored by an equilateral triangle formed by Christ’s body. He sits below an arching pediment that, if completed, traces a circle.

Leonardo rendered a verdant landscape beyond the windows. Often interpreted as paradise, it has been suggested that this heavenly sanctuary can only be reached through Christ.

The twelve apostles are arranged as four groups of three and there are also three windows. The number three is often a reference to the Holy Trinity in Catholic art. In contrast, the number four is important in the classical tradition (e.g. Plato’s four virtues).

Leonardo simplified the architecture, eliminating unnecessary and distracting details so that the architecture can instead amplify the spirituality. The window and arching pediment even suggest a halo. By crowding all of the figures together, Leonardo uses the table as a barrier to separate the spiritual realm from the viewer’s earthly world.[1]

Bartholomew, James Minor, and Andrew (detail), Leonardo da Vinci, Last Supper, oil, tempera, fresco, 1495–98 (Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

- Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, "Leonardo, Last Supper," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed March 2, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/leonardo-last-supper/ ↵