James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889

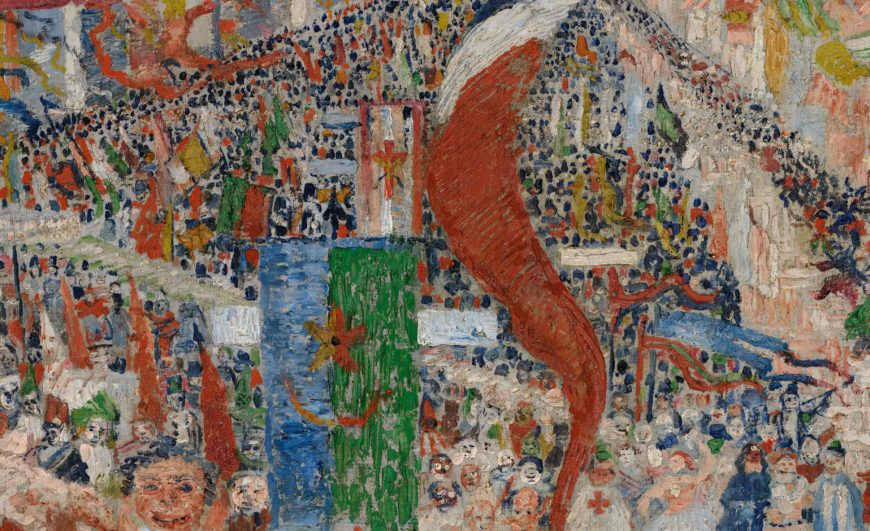

James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 is one of the largest and most ambitious modern paintings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Over eight feet high and fourteen feet wide, it depicts a huge parade flooding down a wide street toward the viewer. The deep central space framed by reviewing stands and balconies suggests the stage of a proscenium theater. The lurid colors used to paint people, signs, and banners clash, and dozens of grotesque theatrical faces in the crowd, many wearing masks, compete for our attention. In the foreground the raucous mob threatens to spill out of the canvas and sweep us up into the chaos.

The painting’s style and technique are as aggressive as its subject. The paint is applied in crude heavy strokes and slabs to create a rough, heavily-textured surface. Bright red dominates, and it is accompanied by its complement, green, as well as the other primaries blue and yellow. There is no shading, and the overall effect is flat and poster-like. The colors are brighter and lighter in the background, which sparkles with patterns of dots representing the distant crowds and rays of light that criss-cross the waving banners.

Humanity mocked

The painting’s title refers to the tradition of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, here transposed to contemporary Belgium. The painting is also reminiscent of the carnival parades of Mardi Gras, the Christian festival that precedes Lent. The small gold-haloed figure of Christ rides a donkey in the center of the painting’s upper portion behind the marching band. He is surrounded by a small group of masked figures whose long noses point up at him, and he raises his arm in a gesture of blessing. Most of the crowd, however, pays no attention to Christ.

Christ’s Entry into Brussels is far from being a conventional religious image of Christ as the savior of humanity. The painting mocks humanity, as well as human beliefs and institutions, both civic and religious. The grotesque parade is led by a bishop dressed in red with a gold miter who is marching out of the painting in the middle of the foreground.

The sea of masks and faces behind him includes priests, government officials, soldiers, a military band preceded by a heavily-decorated leader, and caricatures of many types of ordinary citizens. A masked man dressed in the blue coat and white sash of the city’s mayor watches the parade from a reviewing stand on the right, accompanied by a group of elaborately-costumed masked figures. Ensor himself appears in profile as the yellow-clad figure in the tall conical red hat on the left.

Political critique or personal expression?

A red banner inscribed with the slogan “Vive la sociale” or “Long live the social [revolution]” stretches across the top of the painting and refers to contemporary politics and social reformers. Ensor’s sources for the painting included newspaper photos of an enormous socialist demonstration held in Brussels in 1886. The image of Christ had direct political significance as well; socialist politicians and writers in nineteenth-century France and Belgium frequently portrayed Christ as an exemplary social reformer who worked to improve the condition of the impoverished masses. Ensor is known to have been supportive of liberal social reforms and highly critical of powerful conservative institutions in Belgium, but Christ’s Entry into Brussels does not clearly support any particular political position. On the contrary, it seems to be a wholesale condemnation of both humanity and human ideologies.

Masks

The masks that are so prominent in Christ’s Entry into Brussels became a central subject for Ensor in the 1880s. His family owned a curiosity shop that sold papier-mâché Carnival masks in the seaside town of Ostend, making masks both personal and highly symbolic objects in Ensor’s work. In Christ’s Entry into Brussels even apparently unmasked figures have mask-like, caricatured faces suggesting that everyone wears some sort of mask. Ensor’s masked figures represent humanity as superficial, hypocritical, and grotesque. Masks also confer anonymity and allow people to act outside social laws without fear of being recognized and punished.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels the theme of personal irresponsibility and freedom is enhanced by the association to a Carnival parade. During Carnival, society’s rules are dropped, and the usual social order is turned upside down; rich and poor switch roles, the beggar becomes king or queen for the day. Carnival is often described as serving as a sort of relief valve for the ordinary pressures of society, as well as a moment when underlying truths are exposed. In Christ’s Entry into Brussels the masks can be understood as revealing rather than hiding the true nature of humanity and human society.[1]

- Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, "James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889," in Smarthistory, June 28, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/ensor-christs-entry/. ↵