Introduction to the Inka

The Inka, like the Aztecs (or Mexica) of Mesoamerica, were relative newcomers to power at the time of European contact. When Francisco Pizarro took the Inka ruler (or Sapa Inka) Atahualpa hostage in 1532, the Inka empire had existed fewer than two centuries. Also like the Aztecs, the Inka had developed a complex culture deeply rooted in the traditions that came before them. Their textiles, ceramics, metal- and woodwork, and architecture all reflect the materials, environment, and cultural traditions of the Andes, as well as the power and ambitions of the Inka empire.

An Empire of Roads—and Cords

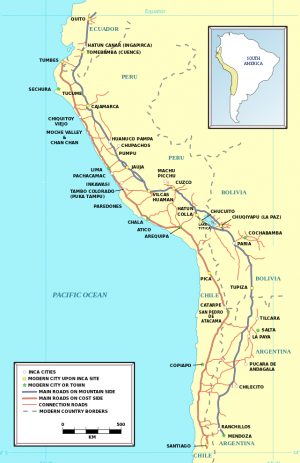

The Inka empire at its greatest extent sprawled from the modern-day city of Quito in Ecuador to Santiago in Chile. The Inka called their empire Tawantinsuyu, usually translated as “Land of the Four Quarters” in their language, Quechua. At the center of the empire was the capital city of Cusco. [Cusco means “navel of the world” in Quechua] The empire was connected by a road system—the Qhapaq Ñan—that was used for official Inka business only. Soldiers, officials, and llama caravans carrying food, ceramics, textiles, and other items used the roads, and so did message runners.

The messages that these runners carried were not written in the way we would expect. They were not made of marks on paper, stone, or clay. They were, instead, encoded into a knotted string implement called a quipu. [pronounced kee-poo] Our knowledge of quipu remains limited. We have been able to determine only some of the ways that the quipu were used. Researchers continue to investigate this unique system of communication. The knots along the various cords recorded numbers, so that a knot with 5 loops could represent the number 5. The position on the cord could then determine what the number meant in a decimal system, so that a 5-loop knot could represent the number 5, or 50, or 500, and so forth.

The cords of quipus are frequently composed of different natural and dyed colors, but the reason or meaning behind those colors so far eludes scholars. The numbers encoded in the quipus helped the Inka keep track of the tax-paying obligations of their subjects, record population numbers, harvest yields, herds of livestock, and other important information. Also recorded on the quipu were stories—histories of the Inka and other social information. However, scholars today still don’t know how that information was encoded into the quipu.

More valuable than gold

Quipus and other Inka fiber objects were made from yarn spun from alpaca fibers. Alpacas and llamas were important to the functioning of the Inka empire, but they had been essential to the lives of Andeans for millennia. Llamas provided meat as well as acting as beasts of burden—an adult male llama can carry up to 100 pounds. Alpacas provided soft, strong wool for textiles and rope-making.

When the Spaniards encountered the Inka, they were confused by the fact that they considered textiles more valuable than gold. Textiles were integral to the structure of the Inka empire. Acllas, or “chosen women,” were kept in seclusion by the Inka to weave fine textiles (called qompi). These textiles mostly took the form of tunics and mantles. Some were distributed as high-status gifts by the Sapa Inka to cement the loyalty of local lords throughout the empire. Others were burned as sacrifices to Inti, the sun god and divine ancestor of the Inka ruling class. This shows us just how highly the Inka regarded textiles: they were fit for a god.[1]

- Dr. Sarahh Scher, "Introduction to the Inka," in Smarthistory, September 15, 2017, accessed April 17, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/inka-intro2/ ↵