Introduction to Land Art and Smithson’s Spiral Jetty

Closely related to both the Conceptualists and Minimalists are those artists who, in the 1960s began to make site-specific art. (Such art defines itself in relation to the particular place for which it was conceived.) Many of these were earthworks, conceived as enormous mounds and excavations made in the remote regions of the American West. One of the primary motivations for making them was to escape the gallery system.

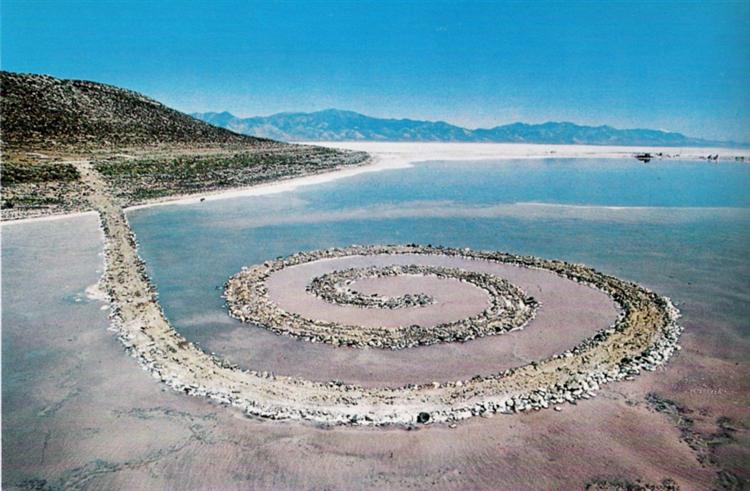

One of the most famous of works designed specifically to escape the gallery system is Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, created in 1970. Using dump trucks to haul rocks and dirt, Smithson created a simple spiral form in the Great Salt Lake. The work is intentionally outside the gallery system, in the landscape – and in a relatively inaccessible and inhospitable portion of the Utah landscape at that. Smithson chose the site, on the shores of the Great Salt Lake about 100 miles north of Salt Lake City and 15 miles south of the Golden Spike National Historic Monument, where the Eastern and Western railroads met in 1869, connecting both sides of the American continent by rail, because, in his mind, it was the very image of entropy, the condition of decreasing organization or deteriorating order. For Smithson, the condition of entropy is not only the hallmark of the modern, but the eventual fate of all things.

Smithson’s work on the jetty coincided with the rise of ecology as a wider public issue. Smithson’s jetty was, as a result widely understood as a work of environmental art. As he was constructing the jetty, Smithson made a film of the event. The typical camera angle is aerial, looking straight down at the surface of the lake from above, so that the spiral seems to lie flat, like a two-dimensional design. The image reinforces the spiral’s status as one of the most widespread of all ornamental and symbolic designs on earth, suggesting too, the motion of the cosmos. The spiral is also found in three main natural forms: expanding like a nebula, contracting like a whirlpool, or ossified as in a snail’s shell. Smithson’s work suggests the ways in which these contradictory forces are simultaneously at work in the universe.[1]

- Henry Sayre, The Humanities: Culture, Continuity and Change, vol. 2, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2015), 1293-1294. ↵