Introduction to Flanders

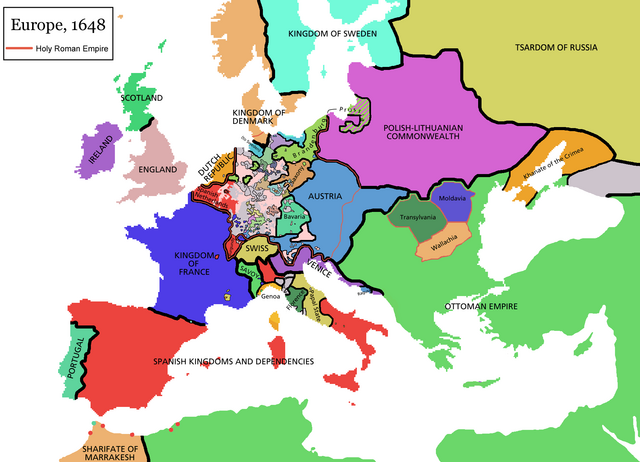

During the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, numerous geopolitical shifts occurred in Europe as the fortunes of individual countries rose and fell. Pronounced political and religious friction resulted in widespread unrest and welfare. Indeed, between 1562 and 1721, all of Europe was at peace for a mere four years. The major conflict of this period was the Thirty Years’ War (1616-1648), which ensnared Spain France, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Poland, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Roman Empire. Although outbreak of the war had its roots in the conflict between militant Catholics and militant Protestants, the driving force quickly shifted to secular, dynastic, and nationalistic concerns. Among the major political entities vying for expanded power and authority in Europe were the Bourbon dynasty of France and the Habsburg dynasties of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. The war, which concluded with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, was largely responsible for the political restructuring of Europe. As a result, the United Provinces of the Netherlands (the Dutch Republic), Sweden, and France expanded their authority. Spanish and Danish power diminished. In addition to reconfiguring territorial boundaries, the Treaty of Westphalia in essence granted freedom of religious choice throughout Europe. This treaty thus marked the abandonment of the idea of a united Christian Europe, and accepted the practical realities of secular political systems. The building of today’s nation-states was emphatically under way.

In the sixteenth century, the Netherlands had come under the crown of Habsburg Spain when Emperor Charles V retired, leaving the Spanish kingdoms, their Italian and American possessions, and the Netherlandish provinces to his only legitimate son, Philip II (r. 1556-1598). (Charles bestowed his imperial title and German lands on his brother.) Philip’s repressive measures against the Protestants led the northern provinces to break from Spain and establish the Dutch Republic. The southern provinces remained under Spanish control and retained Catholicism as their official religion. The political distinction between modern Holland and Belgium more or less reflects this original separation, which in the seventeenth century signaled not only religious but also artistic differences.[1]

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 611. ↵