Introduction to Dada, Hugo Ball and “Karawane”

When the Great War broke out in August 1914, most European leaders thought it would be over by Christmas. Both sides reassured their populations that the efficiency of their armies and bravery of their soldiers would ensure a speedy resolution and that the political status quo would resume. These hopes proved illusory. World War I was the most brutal and costly in human history to date. On the Western Front in 1916 alone, Germany lost 850,000 soldiers, France 700,000, and Great Britain 400,000. The conflict settled into a vicious stalemate on all fronts as each side deployed new killing technologies such as improved machine guns, flame throwers, fighter aircraft, and poison gas. On the home front, governments exerted control over industry and labor to manage the war effort, and ordinary people were forced to endure food rationing, propaganda attacks, and shameless war profiteering.

Horror at the enormity of the carnage and loss arose on many fronts. One of the first artistic movements to address the slaughter and the moral questions it posed was Dada. If Modern art until that time questioned the traditions of art, Dada went further to question the concept of art itself. Witnessing how thoughtlessly life was discarded in the trenches, Dada mocked the senselessness of rational thought and even the foundations of modern society. It embraced a “mocking iconoclasm,” even in its name, which has no real or fixed meaning. Dada is baby talk in German; in French it means “hobbyhorse,” in Romanian and Russian, “yes, yes.” Dada artists annihilated the conventional understanding of art as something precious, replacing it with a strange and irrational art about ideas and actions rather than about objects.

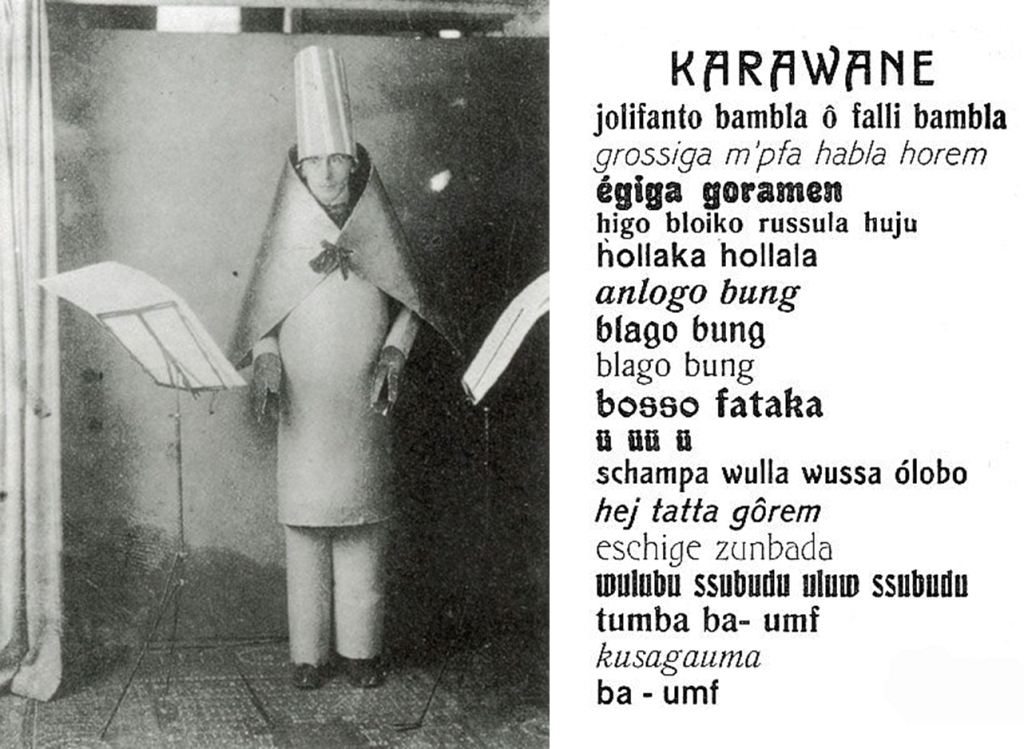

Dada’s opening moment was probably the first performance of poet Hugo Ball’s poem “Karawane” at the Cabaret Voltaire.

Hugo Ball (1886-1927) and his companion Emmy Hennings (d. 1949), a nightclub singer, moved from Germany to neutral Switzerland when World War I broke out and opened the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich on February 5, 1916. Their cabaret was based loosely on the bohemian artists’ cafés of prewar Berlin and Munich. Ball recited his sound poem “Karawane” while wearing a strange costume, with his legs and body encased in blue cardboard tubes and a white-and-blue “witch doctor’s hat,” as he called it, on his head. He also wore a huge, gold-painted cardboard cape that flapped when he moved his arms and lobster-like cardboard hands or claws. He solemnly recited his poem, the text of which comprised a list of nonsensical sounds. Ball’s poetry renounced “the language devastated and made impossible by journalism,” and mocked traditional poetry and the rationality of adulthood by creating a new, randomly based and wholly incomprehensible private language that seemed to mimic baby talk.[1]

- Marilyn Stokstad, Art History, vol. 2, 4th ed, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall: 2011), 1036-1037. ↵