Humanism in Renaissance Italy

Much of the artistic output of the Renaissance was the product of a fruitful dialogue between artists and humanists. Wealthy patrons sponsored the careers of humanists and favored artistic works influenced by ideas derived from Greco-Roman antiquity. Artists who were inspired by humanists’ revived interest in antiquity also used ancient Greek and Roman models to inform their works. Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello traveled to Rome to learn the principles of harmony, symmetry, and perspective by viewing its ancient ruins and statuary firsthand, and artists began depicting classical poses and mythological allegories in their paintings.[1] Much of Italian renaissance art—even overtly religious works—was grounded in humanistic principles.

What was humanism?

Humanism was the educational and intellectual program of the Renaissance. Grounded in Latin and Greek literature, it developed first in Italy in the middle of the fourteenth century and then spread to the rest of Europe by the late fifteenth century. This program, called the studia humanitatis, or the humanities, was thought to teach citizens the morals necessary to lead an active, virtuous life, which its proponents contrasted with the contemplative life of ascetic monks and scholars. As a product of the Italian city-state republics, humanism was a system born in the city and made for the citizen. Although scholars in earlier centuries had embraced classical learning, humanists rediscovered many lost texts, read them with a critical and secular eye, and, through them, forged a new mentality that shaped Italian and European society from from approximately the mid-14th to the mid-17th centuries.

Who were the humanists?

Humanists were the first western scholars to argue for a nobility of spirit, based on merit and skill, rather than a nobility of blood, based on lineage and ancestry. Most humanists found work as professors, librarians, and secretaries for princes and state chanceries. The prime goal of most humanists was to find a patron willing to support their intellectual activities.

The humanist agenda

Humanists sought to rediscover lost and forgotten texts, purge them of mistakes made bymonastic scribes through a rigorous philological analysis, and circulate them in handwritten copies (later, with the advent of the printing press, humanists began to publish printed versions of these texts). In the mid-fifteenth century, after the introduction of Greek texts into Italy due to Ottoman attacks on the Byzantine Empire, humanists translated these texts into Latin, making them more accessible to those who could not read Greek. They often made copious annotations in these manuscripts to help the reader understand them. Moreover, they often published their own works which consciously emulated the style and substance of the ancient authors.

At their core, humanists were educators. Humanists wanted a curriculum that would not make theologians but make citizens useful to governments and society. The values of the ancient Romans and Greeks would perfect citizens and help them realize their potential as individuals endowed with free will to know the good and to act on it.

Although having diverse views on philosophical matters, humanists were united by a secular view of humanity’s place in the world. They gave orations on and debated the idea of the dignity of man. This concept gained momentum with the revival of Neoplatonism after Marsilio Ficino’s translation of the entire corpus of Plato’s extant works in 1469 and his harmonizing of Christian theology with Platonic ideas.

Ficino’s pupil, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, took this idea further in his Oration on the Dignity of Man, written in 1486. Pico argued that in the chain of being humans occupied a privileged space due their capacity to learn and grow as individuals. They were the median between God and animal and plant life; and they could become “terrestrial gods” due to this thirst for knowledge or stagnate from ignorance. Human dignity lay in this free will—humans could choose where they stood in the chain of being and played a role in shaping themselves and the world.

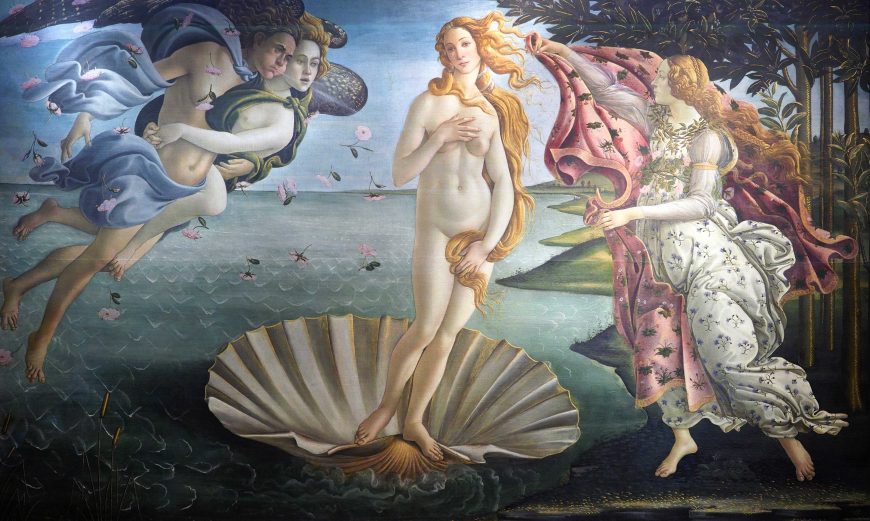

Moreover, humanists not only praised human dignity but also the human body. Rather than being something to hide and be ashamed of, humanists and artists of the renaissance began to depict for the first time since antiquity favorable images of the nude human body, and on a large scale not seen since antiquity. For instance, Venus was portrayed in her classical pose, the Venus pudica—naked but modestly covering her nudity with her arms and long hair rather than as a fully clothed aristocratic woman, as medieval artists had portrayed the goddess. The motif of the Venus pudica is best represented by Botticelli’s Birth of Venus commissioned by the Medici family in the early 1480s. Even biblical figures could be portrayed in their human nakedness. Nothing like this was possible before 1400 since medieval moralists had nothing but contempt for the human body, seeing it as a receptacle of sin and generally depicted it negatively.[2]

- Vasari tells us that Brunelleschi went to Rome to measure the ancient ruins. Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 116–17. ↵

- Dr. John M. Hunt, "Humanism in renaissance Italy," in Smarthistory, August 1, 2021, accessed February 21, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/humanism-renaissance-italy. ↵