Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece

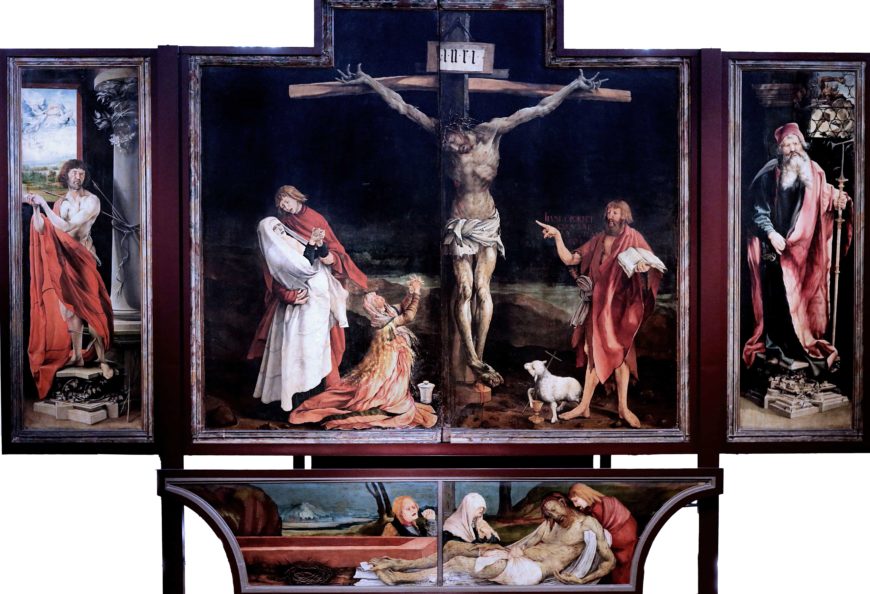

If one were to compile a list of the most fantastically weird artistic productions of Renaissance Christianity, top honors might well go to Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Constructed and painted between 1512 and 1516, the enormous moveable altarpiece, essentially a box of statues covered by folding wings, was created to serve as the central object of devotion in an Isenheim hospital built by the Brothers of St. Anthony. St. Anthony was a patron saint of those suffering from skin diseases.

At the Isenheim hospital, the Antonine monks devoted themselves to the care of sick and dying peasants, many of them suffering from the effects of ergotism, a disease caused by consuming rye grain infected with fungus. Ergotism, popularly known as St. Anthony’s fire, caused hallucinations and skin infection, and attacked the central nervous system, eventually leading to death.

Exterior – panels closed

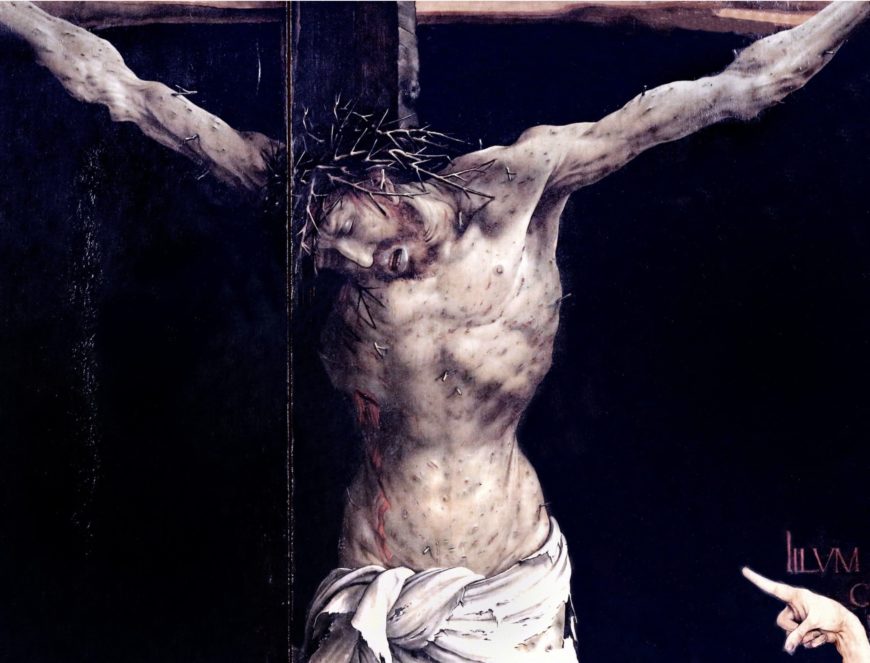

Grünewald’s painted panels come from a different world; visions of hell on earth, in which the physical and psychological torments that afflicted Christ and a host of saints are rendered as visions wrought in dissonant psychedelic color, and played out by distorted figures—men, women, angels and demons—lit by streaking strident light and placed in eerie other-worldly landscapes. The painted panels fold out to reveal three distinct ensembles. In its common, closed position the central panels close to depict a horrific, night-time Crucifixion.

The macabre and distorted Christ is splayed on the cross, his hands writhing in agony, his body marked with livid spots of pox. The Virgin swoons into the waiting arms of the young St. John the Evangelist while John the Baptist, on the other side (not commonly depicted at the Crucifixion), gestures towards the suffering body at the center and holds a scroll which reads “he must increase, but I must decrease.” The emphatic physical suffering was intended to be thaumaturgic (miracle performing), a point of identification for the denizens of the hospital. The flanking panels depict St. Sebastian, long known as a plague saint because of his body pocked by arrows, and St. Anthony Abbot.

First Opening

The second position emphasizes this promise of resurrection. Its panels depict the Annunciation, the Virgin and Child with a host of musical angels, and the Resurrection. The progression from left to right is a highlight reel of Christ’s life. All three scenes are, however, highly idiosyncratic and personal visions of Biblical exegesis; the musical angels, in their Gothic bandstand, are lit by an eerie orange-yellow light while the adjacent Madonna of Humility sits in a twilight landscape lit by flickering, fiery atmospheric clouds.

The Resurrection panel is the strangest of these inner visions. Christ is wreathed in orange, red and yellow body halos and rises like a streaking fireball, hovering over the sepulcher and the bodies of the sleeping soldiers, a combination of Transfiguration, Resurrection and Ascension.

In the predella panel is a Lamentation, the sprawling and horrifyingly punctured dead body of Christ is presented as an invitation to contemplate mortality and resurrection.

Second opening – sculpted altar

Sculpted wooden altars were popular in Germany at the time. At the heart of the altarpiece, Nicolas of Hagenau’s central carved and gilded ensemble consists of rather staid, solid and unimaginative representations of three saints important to the Antonine order; a bearded and enthroned St. Anthony flanked by standing figures of St. Jerome and St. Augustine. Below, in the carved predella, usually covered by a painted panel, a carved Christ stands at the center of seated apostles, six to each side, grouped in separate groups of three. Hagenau’s interior ensemble is therefore symmetrical, rational, mathematical and replete with numerical perfections—one, three, four and twelve.

Hybrid demons

Grünewald saves his most esoteric visions for the fully open position of the altar, in the two inner panels that flank the central sculptures. On the left, St. Anthony visits St. Paul (the first hermit of the desert) in the blasted-out wilderness— the two are about to be fed by the raven in the tree above, and Anthony will later be called upon to bury St. Paul. The meeting cured St. Anthony of the misperception that he was the first desert hermit, and was therefore a lesson in humility.

In the final panel, Grünewald lets his imagination run riot in the depiction of St. Anthony’s temptations in the desert; sublime hybrid demons, like Daliesque dreams, torment Anthony’s waking and sleeping hours, bringing to life the saint’s torment and mirroring the physical and psychic suffering of the hospital patients.[1]

- Dr. Sally Hickson, "Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed March 31, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/grunewald-isenheim-altarpiece/ ↵