Giambologna, Abduction of a Sabine Woman

One of the most recognized works by one of the least well-known artists

Giambologna’s Abduction of a Sabine Woman is one of the most recognized works of sixteenth-century Italian art by one of the least well-known artists of the period. And while Giambologna may not be a household name like Michelangelo, his influence on late sixteenth- and early seventeenth- century European art was extensive and long lasting. The Abduction of a Sabine Woman is located in a spot few tourists miss—the Loggia dei Lanzi, just outside of the Palazzo Vecchio, in Florence.

Giambologna and Mannerism

Giambologna’s works exemplified the characteristics of the Mannerist period, a time in which artists exploited the idea of beauty for beauty’s sake in works that showcased their artistic talent with figures composed of sinuous lines, graceful curves, exaggerated poses, and a hyper-elegance and preciousness that delighted viewers.

The subject

The subject is a dramatic one from ancient Roman history. According to the accounts of both Livy and Plutarch, after the city of Rome was founded in 750 B.C.E., the male population of the city was in need of women to ensure both the success of the city and the propagation of Roman lineage. After failed negotiations with the neighboring town of Sabine for their women, the Roman men devised a scheme to abduct the Sabine women (which they did during a summer festival).

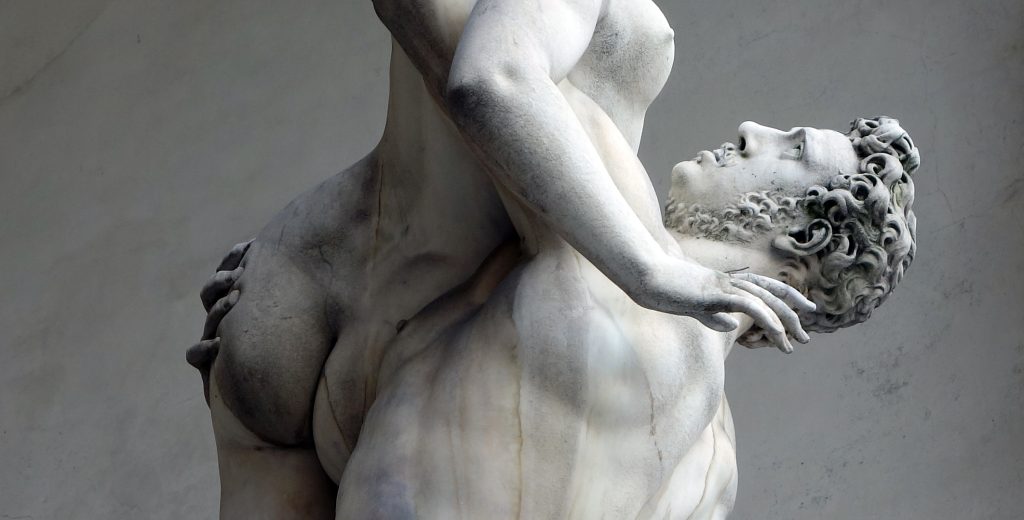

What we see in Giambologna’s sculpture is the moment when a Roman successfully captures a Sabine woman as he marches over a Sabine male who crouches down in defeat. (As a note, the sculpture is also referred to as the Rape of a Sabine Woman, which can lead to confusion over the subject. In Latin, the word rapito means “abduction” (and in Italian, the verb rapire means “to abduct,” thus the title Abduction of a Sabine Woman is technically more correct than the Rape of a Sabine Woman, which has explicit connotations of sexual violence. And indeed, in Livy’s account of the episode, he claims there was not sexual violence, rather a variety of enticements by the Roman for how the women would be treated as their wives.)[2])

Giambologna built his figures up from the bottom, beginning with the cowering Sabine male (above), whose body twists and contorts in reaction to what is happening above him. The man’s straining muscles are evident as he raising his left hand up in despair as the triumphant Roman literally straddles his body, as he strides forward, carrying the Sabine woman away. If you look closely where he grabs her left hip, his fingers actually press into her flesh (below), thus amplifying the effect of these figures being more than marble statues. The woman herself, arms outstretched, twists back and over the Roman’s shoulder as she is hoisted into the air. These figures convey movement, aggression, fear, and struggle, as they move upward in a flame-like or twisting pattern known as figura serpentinata (serpentine figure), popular with Mannerist artists of the period. And to enhance the sense of frenetic energy, Giambologna did not provide a single or primary viewpoint for the work so the viewer must engage with the sculpture in 360 degrees in order to see the entirety of the drama unfold.

- Dr. Shannon Pritchard, "Giambologna, Abduction of a Sabine Woman," in Smarthistory, September 8, 2016, accessed March 9, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/giambologna-abduction-of-a-sabine-woman/. ↵

- Titus Livius, The History of Rome (Ab Urbe Condia Libri, c. 27-25 B.C.E.), Book 1, chapters 9-10. ↵