Caspar David Friedrich, Monk by the Sea and Abby in an Oak Forest

Human destiny is treated with a chilling bleakness and unsettling silence in the sublime landscapes of the German artist Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840). While Turner focuses on the insignificance of all life and endeavors in the face of the all-powerful cosmos, Friedrich’s concern is the passage from the physical way station of earth to the spiritual being of eternity. His landscapes are virtually pantheistic, an especially German phenomenon, and he invests his detailed, realistic scenes with metaphysical properties that give them an aura of divine presence.

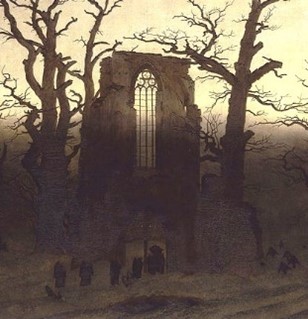

Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea was paired with Abbey in an Oak Forest. The former, which would be hung on the left and read first, pits the small vertical figure of a standing monk against the vastness of an overwhelming explosive sky in a landscape so barren and abstract that the beach, sea, and sky are virtually reduced to vague horizontal bands. Traditionally, art historians interpret the funeral depicted in Abbey as that of this monk, in part because the coffin-bearing Capuchins wear the same habit as that of the Monk by the Sea. If the first picture depicts life contemplating death, this second is an image of death, as suggested by a frozen snow-covered cemetery, a lugubrious funeral procession, distraught barren oak trees, the skeletal remains of a Gothic abbey, and a somber winter sky at twilight. The abbey and oaks, obviously equated, form a gate that the burial cortege will pass under. Religious hope is stated in the crucifixion mounted on the portal. The oval at the peak of the tracery window is echoed by the sliver of a new moon in the sky, a symbol of resurrection. We sense a rite of passage, a direct connection, between abbey and the sky. Just as the moon goes through a cycle as it is reborn, twilight yields to night followed by sunrise and day, and winter gives way to spring, summer and fall; so also, it is suggested, death will be followed by an afterlife or rebirth.[1]

- Penelope J.E. Davies, et. al. Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2007), 834. ↵