Franz Marc and the animalization of art

Expression through color and form

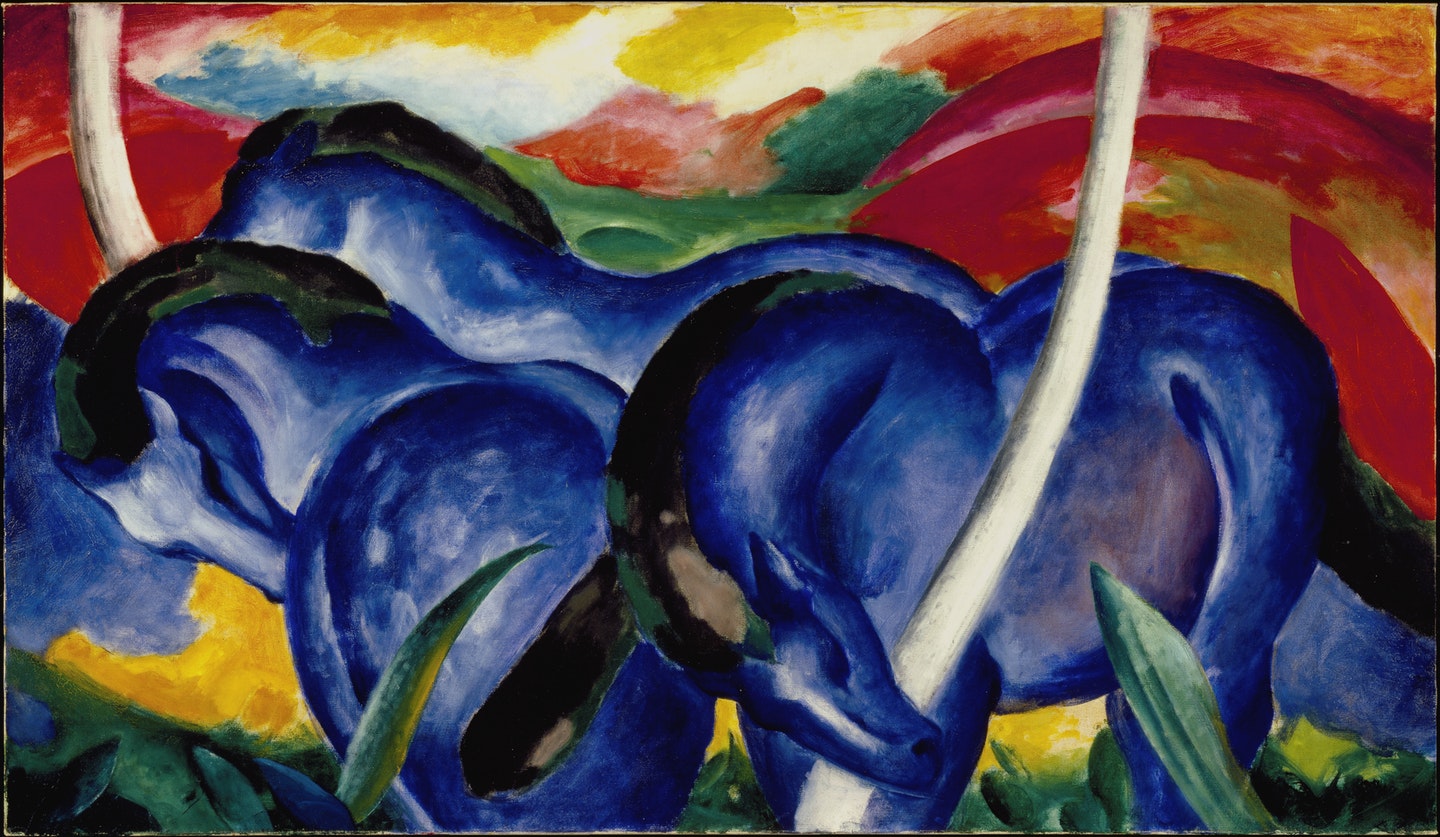

Marc’s animalization of art did not simply entail naturalistic paintings of animals in unspoiled landscapes. Already in The World Cow and Grazing Horses IV, we can see Marc intensifying the color and simplifying the drawing of his subjects, a tactic he takes even further in Large Blue Horses.

In all of these works, Marc uses primary and secondary colors in their most intensely saturated state. Bright red or blue animals graze in vibrant pastures of reds, greens, and yellows underneath rainbow skies. While the proportions, anatomy, and postures of the animals are accurate (he made a living teaching animal anatomy for a time), Marc has increasingly abstracted their forms toward basic, almost geometric shapes that echo into the distant landscape.

Color and energy

Another way to look at Marc’s project is not in terms of objects or the perception of them, but rather in terms of energy and forces. Marc’s description of pantheism as an “organic rhythm,” as “the shivering and coagulating of blood in nature” suggests that the animals and landscape elements themselves are just temporary “coagulations” of matter and energy that are in a constant cycle of birth, life, death, decay, and rebirth. What is permanent and what permeates is the energy coursing through this cycle, expressed in the vibrancy of Marc’s color and the rhythms of his compositions.

Marc’s color theory suggests such a reading:

Blue is the male principle, severe and spiritual. Yellow is the female principle, gentle, cheerful and sensual. Red is matter, brutal and heavy, the color that has to come into conflict with, and succumb to the other two. For instance, if you mix blue — so serious, so spiritual — with red, you intensify the red to the point of unbearable sadness, and the comfort of yellow, the color complementary to violet, becomes indispensable …[1]

The gendering of colors, and especially the association of male with spiritual and female with sensual, is obviously sexist. It is also dubious to assert that colors have such specific and absolute meanings. Red surely signifies something very different in Edvard Munch’s The Scream than it does in Henri Matisse’s Joy of Life.

But we can generalize Marc’s theory to a series of coherent underlying propositions. Colors are not necessarily gendered, but they are generative in the sense that they can be endlessly recombined into new colors or new creations. Viewing colors and color combinations can induce sensations and moods: cheerfulness, heaviness, sadness, and so on. These colors and moods are sometimes harmonious, but sometimes clashing and in conflict.

It is a painter’s job to deploy the emotive and generative qualities of colors in order to produce formal tensions and harmonies that convey various psychological states. This provides an interesting new way to look at his work: one more focused on abstract qualities of design than the subject matter.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Marc was drafted into the German army as a cavalryman. Because of his painting skills, he was put to work for a time camouflaging artillery, and he amused himself by developing patterns inspired by Manet and Kandinsky. Unfortunately, he was later sent to the front, and died in the battle of Verdun on 4 March 1916 — ironically just days before orders came to withdraw him from combat as a notable artist.[2]