The Virgin Mary with the Christ Child seated on a throne

By the late 1200s, large paintings featuring the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child seated on a throne were a common sight in Italian churches. Larger-than-life panels with this theme, a kind of image that came to be known as a Maestà (meaning “majesty”), were adaptations of traditional Byzantine icons for use in devotion in Western Europe. Such paintings may have adorned altars, but they could also have been placed on a beam or wall in the center of a church.

Displayed in this way, large Marian images (images of the Virgin Mary) would have been seen by the crowds gathered to hear Mass. Monumental Maestà panels could also be commissioned by lay confraternities—organizations of laypeople who performed acts of piety and service, and gathered to sing hymns of praise to the Virgin. Wherever they might be placed within a church, these imposing, gilded paintings were objects of intense devotion.

Santa Trinita Madonna

At an unknown date, probably around 1280, the Florentine artist Cimabue painted a celebrated Maestà for the church of Santa Trinita in Florence. Now housed in the city’s Uffizi Gallery, this massive painting—over twelve feet tall and seven feet wide (12’8’’ x 7’4’’)—features Mary gazing out at the viewer. She gestures toward the child with her right hand, while Christ raises his hand in a priestly pose of blessing, an adaptation of the ancient Byzantine icon type (known as the “Hodegetria”) in which the Virgin Mary points to Christ as the way to heaven. The Byzantine icons that inspired Cimabue and other artists of his day also often included angels posed on either side of the throne, usually shown in much smaller scale than Mary to emphasize her importance.

In the Santa Trinita Madonna and other Maestà panels he painted, however, Cimabue makes the angels much larger, and stacks them around the throne so that they seem to be occupying the same space as Mary and Christ. The angels also become interlocutors between the viewer and the holy figures; six of the angels look out toward us directly, while the two in the center gaze at Christ, modeling the pious focus a viewer would imitate.

Set against a gleaming gold leaf background, Mary and Christ sit on a monumental throne fashioned of intricately carved wood and studded with gems. This throne has often been celebrated by art historians as an example of how Cimabue experimented with perspectival effects. The curved steps of the throne lead the eye back into the fictional space Cimabue creates, making it seem as though the figures occupy real space. The large throne also allows Cimabue to place the Virgin and the eight angels that surround her at the top of the composition, foreshortening the front parts of the throne and bringing them closer to the viewer, creating the illusion of depth on the painting’s flat surface.

The four figures below

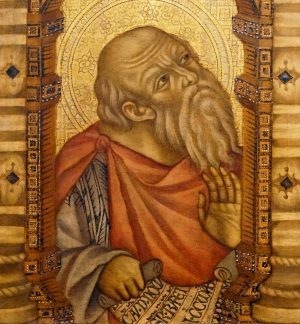

But Cimabue’s most striking and novel element is the inclusion of four bust-length, haloed figures beneath Mary and Christ, enclosed within the arches of the throne’s base. This arrangement foreshadows a trend seen in later altarpieces called a predella—a lateral band of smaller images placed below a larger image. Placed in the foreground, these figures seem to be closer to the viewer than Mary and Christ, further enhancing the sense of three-dimensionality within the painting.

In the Santa Trinita Madonna, the men at the base of Mary’s throne are the heroes and prophets Jeremiah, Abraham, David and Isaiah, identified by the scrolls they hold displaying biblical texts associated with each of them (from Jeremiah 31:22; Genesis 22:18; Psalms 131:11; Isaiah 7:14). These figures from the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament) are included because they each—according to Christian theology—foretold or made possible the coming of Christ (Jeremiah and Isaiah prophesized the coming of the Messiah via a virgin, and Abraham and David were believed to be direct ancestors of the Virgin and Christ). Isaiah and Jeremiah look upwards towards Mary, and each holds an open palm towards the viewer. David gestures similarly, looking towards Abraham, who holds his scroll with both hands and gazes outward from the picture plane. The inclusion of these four men below Mary’s throne glorifies the prophetic heritage and priestly genealogy of Mary and her son.[1]

- Dr. Holly Flora, "Cimabue, Virgin and Child Enthroned, and Prophets (Santa Trinità Maestà)," in Smarthistory, November 4, 2020, accessed February 14, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/cimabue-maesta/ ↵