An upright shadow-box, hardly a foot tall and a few inches thick, is fronted with a glass pane. In it stands a notepad-holder, featuring a substantially proportioned black woman with a grotesque, smiling face. She is clad in a red dress with floral patterns, a yellow polka-dotted scarf, and a red-and-white bandana tied in a knot above her forehead. The woman carries a broom in her right hand, while her folded left hand, with a rifle leaning on it, rests on her waist. The barrel of a pistol appears in the gap between her body and right arm. The space where the notepad was originally held, which covers the lower half of the woman, shows a painting of a similar woman standing in front of vegetation and a picket fence, carrying a crying white child. The lower half of this painted figure is concealed by an upright black fist. The floor of the box is filled with cotton and cotton pods, while the background shows repeated images of the logo of a smiling woman representing the Aunt Jemima brand of breakfast foods.

Such co-existence of a variety of found objects in one space is called assemblage, a type of sculpture that emerged in modern art in the early twentieth century. One of the pioneers of this sculptural practice in the American art scene was the self-taught, eccentric, rather reclusive New York-based artist Joseph Cornell, who came to prominence through his boxed assemblages. There is no question that the artist of this shadow-box, Betye Saar, drew on Cornell’s idea of miniature installation in a box; in fact, it is possible that she made the piece in the year of Cornell’s passing as a tribute to the senior artist. There is, however, a fundamental difference between their approaches to assemblage as can be seen in the content and context of Saar’s work.

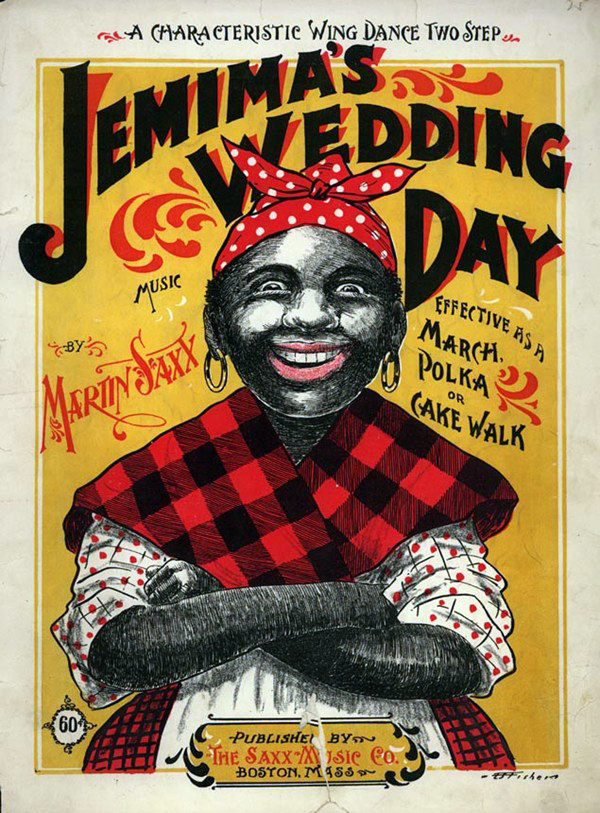

The Mammy caricature in the Jim Crow era

The central item in the scene—the notepad-holder—is a product of the Jim Crow era, a period of violent repression and racial segregation that lasted from approximately the 1890s to the 1960s. The hope and optimism that African Americans felt after the defeat of the Confederacy in the American Civil War (1861–65) and the end of slavery were soon eclipsed by the end of the federal government’s Reconstruction policy in the southern states. Without the might of the federal government to enforce Black civil rights, the formerly rebel states regained the power to maintain a white supremacist system in the south, where Black people would occupy the lowest rung of the socio-economic ladder.

The Jim Crow era that followed Reconstruction was one in which southern Black people faced a brutally oppressive system in all aspects of life. In addition to depriving them of educational and economic opportunities, constitutional rights, and respectable social positions, the southern elite used the terror of lynching and such white supremacist organizations as the Ku Klux Klan to ruthlessly enforce the Jim Crow hierarchy. What is more, determined to keep Black people in the margin of society, white artists steeped in Jim Crow culture widely disseminated grotesque caricatures that portrayed Black people either as half-witted, lazy, and unworthy of human dignity, or as naïve and simple people that fostered nostalgia for the bygone time of slavery.

Inventing various Black stock characters that appeared repeatedly in songs, poems, black-face minstrelsy, and other literary and popular performative genres, white artists created a specific visual culture that presented Blackness as ugly and expendable. Pictorial images of black inferiority in magazines, advertisements, and other outlets were extended to a variety of domestic objects, such as ashtrays, furniture, cookie jars, and here, a notepad holder, intended to amuse white audiences by debasing the Black body. These images became widely popular not just in the south, but all over the country. Not only did such propaganda foster a deep disregard and disdain for Black people in the white mind, but it also succeeded in infusing the Black mind with an equally deep sense of self-loathing and inferiority. Generations of Black Americans saw themselves, at least in part, through the lens of the dominant culture, convinced of their own inferior status in the racial hierarchy and of the bleakness of their own future. The notepad-holder in Saar’s work, featuring the Mammy caricature, is one such example of Jim Crow art.

The Mammy character was one of the popular Jim Crow inventions recalling what was seen as the “good old days” of slavery. A product of the southern white fantasy of the “happy slave,” she is an overweight, congenial, affectionate woman who served the plantation owner’s household. Her smile, claimed to be a sign of southern hospitality, is actually the most visible marker of her docility and her acceptance of the racial hierarchy of Jim Crow.

In the 1920s, Pearl Milling Company drew on the Mammy archetype to create the Aunt Jemima logo (basically a “normalized” version of the Mammy image) for its breakfast foods. The archetype also became a theme-based restaurant called Aunt Jemima Pancake House in Disneyland between 1955 and 1970, where a “live Aunt Jemima” (played by Aylene Lewis) greeted customers. To further understand the roles of the Mammy and Aunt Jemima in this assemblage, let’s take a quick look at the political scenario at the time Saar made her shadow-box, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima.

Civil Rights and Black Power

From the mid-1950s through the 1960s, the Civil Rights movement was a watershed event in American history. The leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the efforts of grassroots organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), led to the achievement of many of the goals long pursued by African Americans activists in the United States, including the end of southern segregation. Equally consequential in that era was a new wave of the feminist movement that exposed gender oppression in a patriarchal society. By the mid-1960s, many activists within the Civil Rights movement grew critical of what they saw as a largely male-dominated effort, that was more interested in compromises with the existing power structure of American society than with the real empowerment of Black Americans.

Questions arose on the feminist front as well. What, for example, would be the position and priority of a woman of color, who was in a double bind, dominated in the contexts of both gender and race? Should she join hands with the largely upper middle-class white leadership of the feminist movement against Black patriarchy, or fight against white racial hegemony under the largely male Civil Rights leadership? As an alternative to the mainstream Civil Rights movement, the Black Panther party was founded in 1966 as the face of the militant Black Power movement that also foregrounded the role of Black women. Many creative activists were attracted to this new movement’s assertive rhetoric of Black empowerment, which addressed both racial and gender marginalization.

The centrality of the raised Black fist—the official gesture of the Black Power movement—in Saar’s assemblage leaves no question about her political allegiance and vision for Black women. Saar’s decision to supplement the Mammy’s broom with guns is a bold attempt to rescue the character from her demeaning, servile role in Jim Crow fantasy; entirely out of place, the presence of guns resolutely challenges the popular understanding of the Mammy figure. Her feet are planted in cotton (a crop closely associated with slave labor in the south). This fictional product of systemic racism threatens revolt from within her stereotypical context; behind the disguise of docility, her smile can now be interpreted as ominously evocative of revenge. Furthermore, if the fist below is seen as the source of the discomfort of the child carried by the painted Mammy, then that reading intensifies the unsettling mood of the scene. Finally, since Aunt Jemima is yet another fiction derived from the Mammy, the artist logically liberates her by turning the latter into a symbol of resistance to her prescribed role; if there were no enslaved Mammy archetype to begin with, there would be no Aunt Jemima destined to serve white desire, in this case for packaged food.

The revolutionary role of Black women

In the light of the complicated intersections of the politics of race and gender in America in the dynamic mid-twentieth century era marked by the civil rights and other movements for social justice, Saar’s powerful iconographic strategy to assert the revolutionary role of Black women was an exceptionally radical gesture. But this work is no less significant as art. Much of the white, male-dominated American art world in the postwar years was involved in a diverse range of creative experiments, yet the dominant tendency was to skirt, if not totally avoid, thorny social and political issues. The prominent routes included formal experiments like Abstract Expressionism, where the artist’s role as a creator superseded any extraneous associations; Pop, which celebrated consumer culture with an ironic slant; and Minimalism and Conceptual art, both of which were known for esoteric intellectual explorations. For many artists of color in that period, on the other hand, going against that grain was of paramount importance, albeit using the contemporary visual and conceptual strategies of all these movements. Thus, while the incongruous surrealistic juxtapositions in Joseph Cornell’s boxes offer ambiguity and mystery, Saar exploits the language of assemblage to make unequivocal statements about race and gender relations in American society.

Faith Ringgold’s story quilt Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima and Jeff Donaldson’s painting Aunt Jemima Fighting the Pillsbury Doughboy are prominent examples of the same subject addressed by two other notable Black artists. Such innovative transgressions by Black American artists are, without question, groundbreaking contributions to the rich diversity of postwar American art.

***Following decades of protests and appeals, the Aunt Jemima logo was at last removed in 2020. Quaker Oats, the current owner of the brand, also announced that the name of the brand would change back to the Pearl Milling Company.