David Smith, Tony Smith, and Donald Judd

From ancient times, sculptors have frequently created statues for display in the open air. But rarely have sculptors taken into consideration the effects of sunlight in the conception of their works. American sculptor David Smith was an exception.

Smith learned to weld in an automobile plant in 1926 and later applied to his art the technical expertise in handling metals that he gained there. In addition, working on industrial-scale projects helped him visualize the possibilities for large-scale metal sculpture. Nonetheless, his works – for example, Cubi VI – differ from machine-age parts in important ways. Smith usually added gestural elements reminiscent of Abstract Expressionism by burnishing the metal with steel wool, producing swirling, random-looking patterns that draw attention to the two-dimensionality of the sculptural surface. This treatment, which captures the light hitting the artwork activates the surface and imparts a texture to his pieces, a key element of all of his sculptures, which he designed for display outdoors. Indeed, the Cubi lose much of their character in the sterile lighting of a museum.[1]

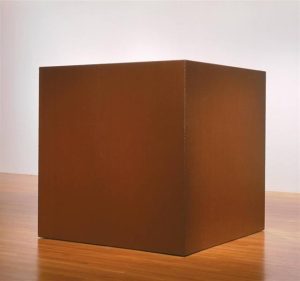

One of the leading Minimalist sculptors was New Jersey native Tony Smith (1912-1980), who created simple volumetric sculptures such as Die. Minimalist artworks generally lack identifiable subjects, colors, surface textures, and narrative elements, and are perhaps best described simply as three-dimensional objects. By rejecting illusionism and reducing sculpture to basic geometric forms, Smith and other Minimalists emphatically emphasized their art’s “objecthood” and concrete tangibility.[2]

Untitled by Donald Judd (1928-1994) is a set of rectangular “boxes” derived from the solid geometric shapes of David Smith’s Cubi series. Judd’s boxes, however, do not stand on a pedestal. Instead, they hang from the wall (and in some cases are placed directly on the floor), thereby involving the immediate environment in the viewer’s experience of them. They are made of galvanized iron and painted with green lacquer, reflecting the Minimalist preference for industrial materials. Judd has arranged the boxes vertically, with each one placed exactly above another at regular intervals, to create unvarying repetition. The shadows cast on the wall, which vary according to the interior lighting, participate in the design. They break the monotony of the repeated modules by forming trapezoids between each box, and between the lowest box and the floor. The shadows also emphasize the vertical character of the boxes’ alignment by linking them visually and creating the impression of a modern, non-structural pilaster.[3]

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 842. ↵

- red S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 842. ↵

- Laurie Schneider Adams, Art Across Time, vol. 2, 4th ed., (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011), 926-927. ↵