A beginner’s guide to Realism

The nineteenth century was an age of revolutions–economic, social, and political–and these, like contemporary ideas about human rights, can be traced to the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. Resulting conflicts between different classes of society were often implicit in works of art, usually depicted from the viewpoint of those rebelling against political oppression.

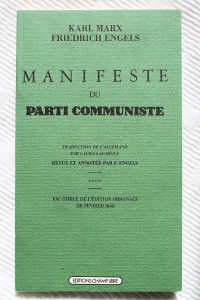

A major force in polarizing social classes was the industrial revolution, which began in England, transforming the economies, first of western Europe and then other parts of the world. Factories were established mainly in urban areas, and people moved to cities in search of work. New social class divisions arose between factory owners and workers. Demands for individual freedom and citizens’ rights were accompanied in many European countries by social and political movements for workers’ rights. In 1848, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published the most influential of all political tracts on behalf of workers: the Communist Manifesto.

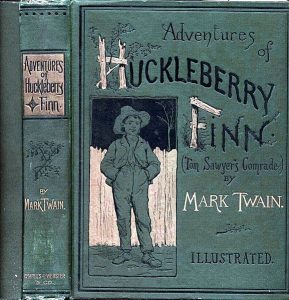

Novelists such as Charles Dickens and Mark Twain described the broad panorama of society as well as the psychological motivations of their characters. In science, the observation of nature led to new theories about the human species and its origin. The proliferation of newspapers reflected the expanding communications technology, and inventions such as the telegraph and telephone increased the speed with which messages and news could be delivered.

In the visual arts, the style that corresponded best to the new social awareness is Realism. The term was coined in 1840, although the style appeared well before that date. The primary concerns of the Realist movement in art were direct observation of society and nature, as well as political and social satire..[1]

The father of Realism in the visual arts was Gustave Courbet. In the fall of 1849, returned from Paris to Ornans, and there in his family’s attic painted the 22-foot wide Burial at Ornans, which was accepted at the Salon of 1850-51. The picture was an affront to many viewers. It presented common provincial folk, portrayed in a course, heavy form, without a shred of elegance or idealization. The bleak overcast landscape is equally authentic, based on studies made at the Ornans cemetery. Despite bold brushwork and a chiaroscuro vaguely reminiscent of his favorite artists Rembrandt and Velazquez, the picture has no Baroque drama and no compositional structure designed to emphasize one figure over another—the dog is as important as the priest or mayor. The picture seems so matter-of-fact it is difficult to know what it is about. We see pallbearers and coffin on the left, then a priest and assistants, followed by small-town patricians, and to the right, women. An open grave is in the foreground center. Clearly, the picture is a document of social ritual that accurately observes the distinctions of gender, profession, and class in Ornans. At every turn, Courbet challenged academic values. He replaced the hallowed Greek and Roman tradition with bold images of the contemporary world and daringly troweled paint into the canvas, undermining the refinement of academic paint handling technique.[2]

- Dr. Beth Gersh-Nesic, "A beginner’s guide to Realism," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed March 16, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/a-beginners-guide-to-realism/ ↵

- Penelope J.E. Davies, et. at. Janson's History of Art: The Western Tradition, 7th edition (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2007), 863. ↵