Action Painting – Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning

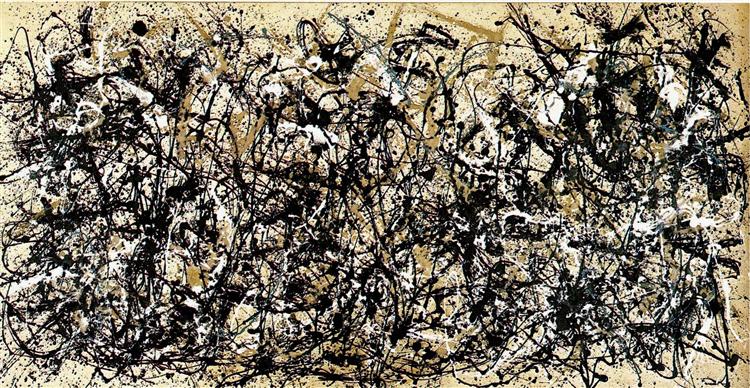

Through the 1930s, Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) was a marginal figure in the art world who worked odd jobs, including being a custodian at what is today called the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. His big break came in 1943 when Peggy Guggenheim exhibited his work at her gallery, Art of This Century, and gave him a stipend to paint. In his final show with Guggenheim in 1947, he unveiled his first gesture or action paintings, the latter term coined in the 1950s by art critic Harold Rosenberg and represented here by Autumn Rhythm: Number 30 of 1950, an 8 x 17-foot wall of house paint that was applied by dripping, hurling, and splattering when the unstretched canvas was on the floor.

Pollock had worked on it from all four sides, and he claimed that its source was his unconscious. Despite the apparent looseness of his style, Pollock exerted great control of his medium by changing the viscosity of the paint, the size of the brush or stick he used to apply the paint, and the speed, size, and direction of his own movements, and he rejected many paintings when the paint did not fall as anticipated. The energy of the painting is overwhelming, and from its position on a wall the work looms above us like a frozen wave about to crash. There is no focus upon which the eye can rest. Because of these even stresses throughout the image, Pollock’s compositions are often described as allover paintings.

Pollock’s style was too personal to spawn significant followers. The gesture painter who launched an entire generation of painters was William de Kooning (1904-1997), a Dutch immigrant, who quietly struggled at his art for decades in New York’s Greenwich Village. He finally obtained a one-person show in 1948, at the Egan Gallery when he was 44. De Kooning shocked the art world with his second exhibition held at the Sidney Janis Gallery in 1953. He did the unthinkable for an Abstract Expressionist: He made representational paintings, depicting women, as seen in Woman I.

De Kooning reportedly painted and completely repainted Woman I hundreds of times on the same canvas, and he made numerous other paintings of women in the summer of 1952. The process of making the picture was almost as important as the final product, as though it were a ritualistic catharsis of sorts. The final figure in Woman I is by far the most violent and threatening of the series. De Kooning was surprised that viewers did not see the humor in his threatening, wide-eyed, snarling figure, which was based as much on contemporary advertisements of models smoking Camel cigarettes as on primitive fertility goddesses, such as the Paleolithic Woman of Willendorf, both of which the artist cited as sources.[1]

- Penelope J.E. Davies, et. al. Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2007), 1039-1041. ↵