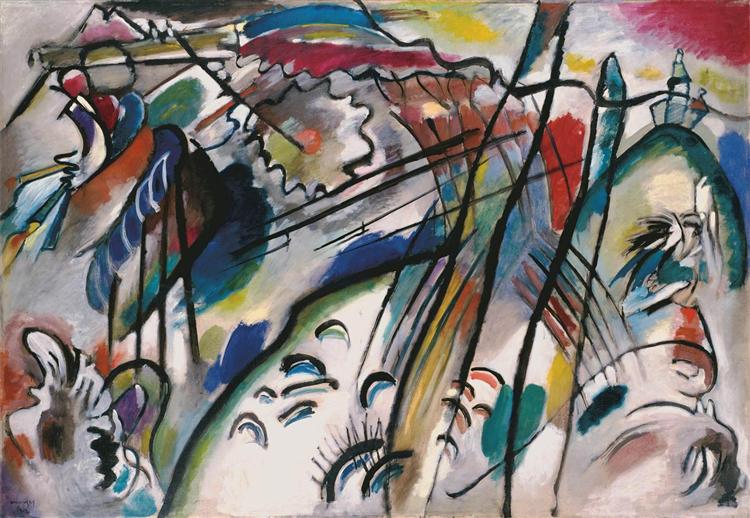

Vasily Kandinsky, Improvisation 28

Vasily Kandinsky was one of the first artists to investigate the theoretical possibility of purely abstract painting. He gave his works musical titles, such as “Composition” and “Improvisation,” and aspired to make paintings that responded to his inner state rather than an external stimulus and which would be entirely autonomous, making no reference to the visible world.

In 1912, he painted a series of works, including Improvisation 28, that he claimed was the first truly abstract art. In these, Kandinsky’s colors leap and dance, with different colors expressing different emotions. For Kandinsky, painting was a utopian spiritual force. He believed that art’s traditional focus on accurate rendering of the physical world was a basically materialist quest. At should not depend so much on mere physical reality. He hoped that his paintings would lead humanity toward deeper awareness of spirituality and the inner world. Rather than searching for correspondence between the painting and the world where none is intended, the artist asks us to look at the paintings as if we were hearing a symphony, responding instinctively and spontaneously to this or that passage, and then to the total experience.[1]

Color vibrations

In his treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky gives special attention to color’s ability to communicate, not just sensually, but also spiritually:

Generally speaking, color is a power which directly influences the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the [viewer’s] soul.

Vasily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, trans. M. T. H. Sadler (New York 1977), p. 25.

The analogy to music here is telling. Kandinsky believed that music was a more advanced form of art than painting precisely because it was more “abstract.” Music moves us emotionally and spiritually through pure form (sound vibration), without directly representing any real-world content. He believed visual artists could do the same through color vibrations, and make painting a truly spiritual art form.

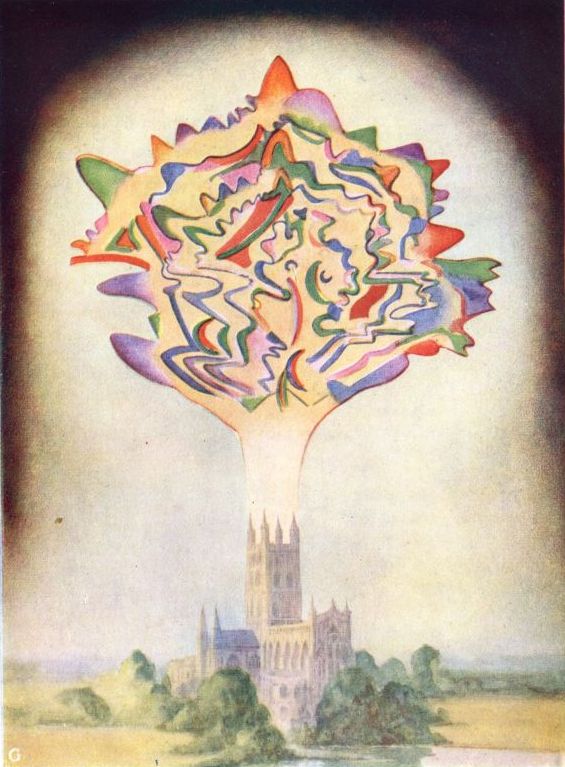

The notion that spiritual states can be conveyed through color patterns would have been familiar to many people in the early-twentieth century. Theosophists believed that certain privileged seers were able to perceive color auras that show a person’s emotional and spiritual condition. The illustration above represents the “astral body” surrounding an “ordinary lower middle-class man,” for example.

Synesthesia

For Kandinsky, the close connections and even transferability among color, music, and spirituality were probably enhanced because he experienced a phenomenon known as synesthesia. This is a condition where sensory “wires” in the brain are in effect crossed, so that a person may experience a color as a sound, or taste as a texture. The English language recognizes this phenomenon in phrases such as “loud color” or “sharp cheese.” In another Theosophical treatise on spiritual auras, there is a striking illustration of synesthesia in the form of an abstract cloud of color emerging from a church tower, illustrating the color equivalent of what is being sung within, “a ringing chorus by [the composer Charles] Gounod.”[2]