Jan Van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait

Emerging capitalism led to prosperity in Europe’s booming urban centers and fueled in turn the growing bourgeois market for art objects, particularly in Bruges, Antwerp, and, later, Amsterdam. The increased wealth of the merchant class contributed to an expanded market for secular art in addition to religious artworks. In the fifteenth century, Flemish patrons eagerly embraced the opportunity to have their likenesses painted. The elite wanted to memorialize themselves in their dynastic lines and to establish their identities, ranks, and stations with images far more concrete than heraldic coats of arms.

-

Jan Van Eyck, Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. Oil on wood, 2’9” x 1’ 10-1/2”. National Gallery, London. - An early example of secular portraiture is Jan van Eyck’s oil painting Giovanni Arnolfini and His Wife. Jan depicted the Lucca financier (who had established himself in Bruges as an agent of the Medici family) in his home. Arnolfini holds the hand of his second wife, whose name is not known. That much is certain, but the purpose and meaning of the double portrait remain the subject of considerable debate. According to the traditional interpretation of the painting, Jan recorded the couple taking their marriage vows. As in the Mérode Altarpiece, almost every object portrayed carries meaning. For example, the little dog symbolizes fidelity. The finial (crowning ornament) of the marriage bed at the right is a tiny statue of Saint Margaret, patron saint of childbirth. (The bride is not yet pregnant, although the fashionable costume she wears makes her appear so.) From the finial hangs a whisk broom, symbolic of domestic care. Indeed, even the placement of the two figures in the room is meaningful. The woman stands near the bed and well into the room, whereas the man stands near the open window, symbolic of the outside world.

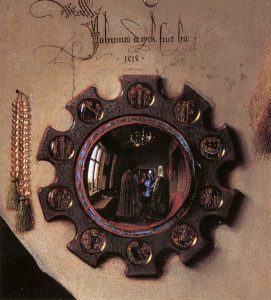

Many art historians, however, dispute this interpretation because, among other things, the room in which Arnolfini and his wife stand is a public reception area, not a bedchamber. One scholar has suggested that Arnolfini is conferring legal privileges on his wife to conduct business in his absence. (This interpretation is strengthened by the fact that the woman wears the headdress of a married woman) In either case, an important aspect of the painting is that the artist functions as a witness to whatever event is taking place. In the background, between the two figures, is a convex mirror, complete with its spatial distortion brilliantly recorded, in which Jan depicted not only the principals, Arnolfini and his wife, but also two persons who look into the room through the door. One of these must be the artist himself, as the elegant inscription above the mirror Johannes de Eyck fuit hic (“Jan van Eyck was here”) announces that he was present. The self-portrait also underscores the painter’s self-consciousness as a professional artist whose role deserves to be recorded and remembered.[1]

- Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, vol. 2, 15th ed., (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2017), 442-443. ↵