Social and Behavioral Science

144 Sleep Quality & Early Life War Exposure: Insomnia Among Vietnamese Older Adults in the Vietnam Health and Aging Study

Sierra Young; Kim Korinek (Sociology); and Yvette Young

Faculty Mentor: Kim Korinek (Sociology, University of Utah)

ABSTRACT

We aim to explore the associations between insomnia, early-life war-related stressors, recent life events, and other health and environmental factors in a sample of 2,447 older Vietnamese adults derived from the 2018 Vietnam Health and Aging Study (VHAS). Insomnia is one of the main symptoms of a variety of adverse health outcomes and sleep disorders but there is a knowledge gap in Low- to Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) like Vietnam. We find that most respondents report moderate to severe insomnia. In ordered logistic regression analyses we find that respondents who served in the military, and who experienced high levels of wartime violence stressors and wartime malevolent conditions, experience more severe insomnia in late adulthood. These associations are mediated by the experience of recent severe PTSD and physical pain. This research makes valuable steps toward understanding war’s enduring scars and global efforts to understand, prevent, and treat sleep problems.

INTRODUCTION

“In peace and war, the lack of sleep works like termites in a house: below the surface, gnawing quietly and unseen to produce gradual weakening which can lead to sudden and unexpected collapse.” —Major General Aubrey Newman (Follow Me, 1981, p. 279)

I. Importance of Healthy Sleep

Sleep is not only comforting and restorative, but essential for our survival. Healthy sleep is characterized by sufficient duration, good quality, appropriate timing and regularity, and the absence of sleep disturbances and disorders (Watson et al., 2015). Since the 1970s, sleep deprivation and disorders have been recognized as a public health concern, but the extent of that concern has emerged mainly in the last two decades (Shepard et al., 2005).

Researchers have associated shorter sleep durations with increased mortality rates, proinflammatory responses, stress responsivity, somatic pain, emotional distress, mood disorders, cognitive deficits, and a reduced quality of life (Kripke et al., 1979; Gildner et al., 2014; Medic et al., 2017). Sleep disorders have also been linked to the development of neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, and dementia (Bombois et al., 2010). Important gender distinctions have also been made. Men tend to report higher sleep quality, while women report longer sleep durations (Gildner et al., 2014). Outside of biological and physiological factors, sleep is also “socially driven, dictated by the environment, and subject to interpersonal and societal factors,” (Grandner, 2017, p. 1).

II. Sleep, Military Service & Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Data from middle-aged and elderly populations of U.S. veterans indicate that one predictor of sleep problems is exposure to war and combat. In the aftermath of war, veterans experience persistent insomnia and nightmares (Gehrman et al., 2016). This is especially the case when moderated by mental health disorders like PTSD (Armenta et al., 2018). Existing research on U.S. military service members indicates that there is a strong positive association between war exposure and enduring sleep problems. In some studies, up to 90% of Vietnam War veterans experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – 92% of which report experiencing significant insomnia (Gehrman et al., 2016). While the question remains whether one has a stronger influence on the other, sleep problems relating to PTSD are shown to become independent over time, evolving into a range of other comorbidities (ibid.). Military studies have generally observed that the risk of PTSD is highest in younger age groups; however, when examining persistence, the severity of PTSD has shown to increase with age (Armenta et al., 2018).

III. Lack of Sleep Research in Low- to Middle- Income Countries

As epidemiological shifts occur worldwide, adequate sleep is becoming more elusive for more people, especially those in lower- to middle-income countries (LMICs). Despite this trend, sleep research has been dominated by and concentrated within high-income populations in temperate climates like the United States and Canada. Most of this research attempts to identify sleep disorders and their correlates, and very few studies attempt to identify associations between early-life war exposure and later-life sleep problems, especially in the developing world (Endshaw, 2012). Inversely, data pertaining to sleep disorders, their relationship to health outcomes, and their potential causes are severely lacking in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially in rural, tropical regions (Simonelli et al., 2018). The populations in these regions are aging faster than their infrastructures can keep up, which means poor sleep quality and its correlates could present challenges at the policy, planning, and scientific levels (Simonelli et al., 2018). There are both theoretical and practical gains to be realized by extending research on sleep and sleep disorder to post-conflict and LMICs. Furthermore, as rapid population aging elevates burdens to elder care and healthcare institutions in many LMICs, and Asian LMICs in particular, understanding the roots of insomnia, and undertaking prevention and treatments to address disordered sleeping, can go a long way in supporting older adult health and wellbeing.

What we do know about sleep in LMICs indicates that sleep disorders are prevalent in older populations, especially among older women, and are linked to the same variety of health consequences from studies in high-income countries. In an in-depth, cross-sectional study of 40,000 older adults from eight African and Asian countries, Vietnam stood out as a nation with a high prevalence of sleep problems (Stranges et al., 2012). Overall, 37.6% of women and 28.5% of men reported severe or extreme problems falling asleep, which was second only to Bangladesh (ibid.) These differences could not be entirely explained by poverty, as certain poorer countries such as Tanzania reported a significantly lower prevalence of sleep problems than Vietnam (ibid.). There is currently no research addressing the causality or temporality of sleep disorders in Vietnam or virtually any developing country other than China.

VIETNAM CONTEXT & BACKGROUND

Studying the Vietnamese older adult population provides ample opportunity for examining the link between early-life war exposure and later-life sleep quality. Vietnam has a long and complex history with war and conflict, but it has achieved a level of stability in the last half-century that allows us to study more direct associations between the American-Vietnam War (1955-1975) and the war cohort’s health outcomes.

I. Before, During, and After the American-Vietnam War

The American-Vietnam War (hereafter “the War”) has been described by General Võ Nguyên Giáp as “the most atrocious conflict in human history,” (Appy, 2003). When the United States resolved to use force in Vietnam, the North Vietnamese government viewed it as one in a long line of wars fought for Vietnamese independence (Laderman & Martini, 2013). They had already been engaged in centuries of conflict – against the Chinese, Japanese, and most recently, France (ibid.). As the War developed, the United States justified its actions by situating the conflict within the context of the Cold War (ibid.). They were simply there to support the Democratic uprising in the South, led by Ngô Đình Diệm and the successors that took his place after his execution (ibid.). They were not expecting that the guerilla fighters of the North would defeat the United States Armed Forces after twenty years of conflict.

The War was a bloody one, and it led to the death of millions and the destruction of the vital infrastructure and landscape in Vietnam (Hirschman, Preston, S., & Loi, 1993). Through relentless bombing campaigns, the United States Air Force destroyed thousands of acres of land in Vietnam and adjacent countries (Miguel & Roland, 2011). This led to the displacement and evacuation of millions of people across the country. Their use of toxic chemicals like Agent Orange caused widespread environmental damage and health problems for not only those who were sprayed, but their posterity too (Leeming, 2015). In an effort to fight back, practically the entire population of Vietnam was involved in one way or another. Men joined military organizations, by choice or compulsion; the North Vietnamese government’s propaganda campaign motivated thousands of women and children to join the Youth Shock Brigades; and others still participated in informal military service organizations or helped the war effort as civilians (Guillemot, 2009 & Nguyen, 2017).

Although the North Vietnamese defeated the United States, causing them to retreat from the conflict on April 30, 1975, the War left Vietnam in a state of ruin. The staggering losses experienced by the Vietnamese people had a profound impact on their society, economy, ecology, politics, family structure, and the individual. The concept of post-traumatic stress disorder was not part of the Vietnamese vernacular at the time, but the traumas of war lingered in the soul and psyche of many untreated veterans of the war (Kwon, 2012). Now, almost fifty years since the end of the war, its assaults on the individual have rarely been studied and its true impact unknown.

II. The Vietnam Health and Aging Study as a Resource

The Vietnam Health and Aging Study (VHAS) is a key resource for understanding potential associations between war and insomnia severity. It utilizes a life-course conceptual framework and longitudinal design structured to examine relationships between early-life war exposures and later-life health outcomes through a variety of associations. The data in this study has been collected in two waves, the first of which occurred in 2018, the second of which, completed in the summer of 2022, collected follow-up information on participants four years later (Korinek et al., 2019). VHAS thus allows for longitudinal analyses and investigation of late life changes in health and wellbeing. The VHAS has previously identified positive correlations between adolescent war exposure and late-life frailty, cardiovascular diseases, and enduring mental health disorders (Zimmer et al., 2021a; Korinek et al., 2020; Kovnick et al., 2021). Further research is being done to assess the relationships between war and sarcopenia, neurodegenerative diseases, and a range of other health outcomes. Overall, the findings have generally supported a life course theory of health that points to long-term effects of war on health and aging (Zimmer et al., 2021b). Further research within Vietnam and among its older adult population makes possible a deeper understanding of the relationship between war and sleep, and the mediating factors underlying these associations, such as PTSD, socioeconomic conditions, recent stress events, and proximate health conditions.

HYPOTHESES

Based upon past research and life course approaches to health, namely the cumulative disadvantage theory (e.g., Ferraro et al. 2009), we formulate the following hypotheses:

1) Older adults who served in the military during their young adulthood are more likely to experience severe insomnia in late adulthood as compared to nonveterans.

2) Insomnia severity will be greater among those older adults who encountered relatively numerous and severe exposures to wartime combat and death, and malevolent environmental conditions of war.

3) Due to their influence upon more proximate risks for insomnia, namely PTSD, pain and recent life event stressors, we hypothesize that the hypothesized associations between military service and war-time stressors will be largely attenuated when these current health and stress conditions are incorporated into our models.

By analyzing a population with highly heterogeneous exposures to diverse war-related stressors, we gain unique insights into the role of life course stress as a risk factor for disordered sleep in late adulthood.

RESEARCH METHODS

I. Study Design and Participants

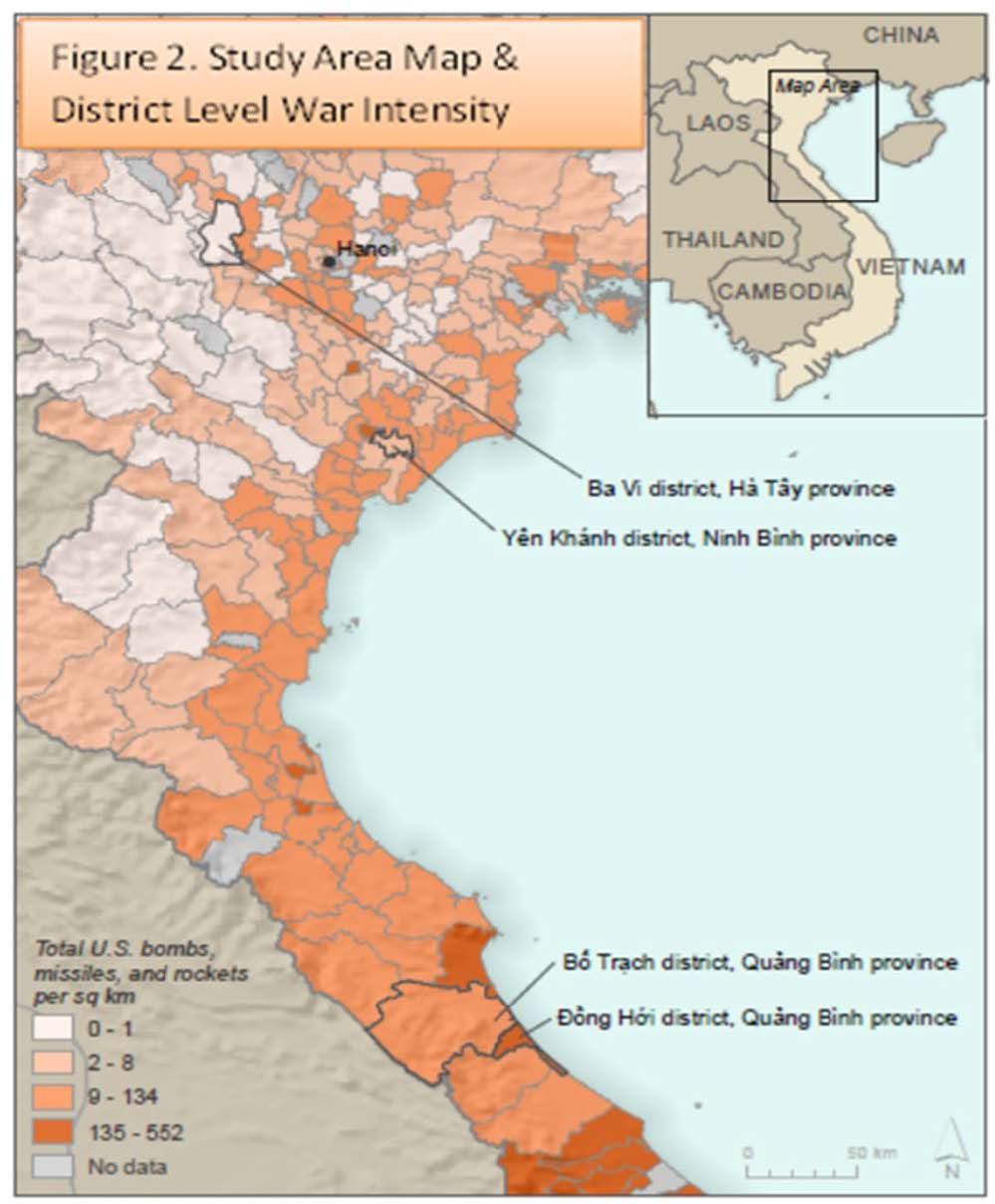

To estimate the correlates of insomnia severity among Vietnamese older adults we analyse data from the 2018 Vietnam Health and Aging Study (VHAS). The VHAS conducted face-to-face survey interviews and biomarker data collection from May to August 2018 with 2,447 Vietnamese adults aged 60 and older (median year of birth, 1950). VHAS study participants reside in four districts of northern and central Vietnam purposively selected to capture geographic diversity in war exposure as indicated by the intensity of bombings across the Democratic Republic of Vietnam during the 1960s and 1970s (see Figure 1; Miguel & Roland, 2011).Within these four districts, 12 communes were randomly selected for data collection, and stratified random sampling methods, with strata delineating gender and military participation, were implemented to select 204 individuals from each of 12 communes (Korinek et al., 2019). Due to the passage of time between the war’s end and VHAS data collection, the sample is selective of those who survived the war, remained in Vietnam, and did not die from other causes prior to 2018. All study participants provided written informed consent to participate, and VHAS received IRB approvals from the University of Utah and Hanoi Medical University. A more detailed description of the VHAS study design and sampling procedures are elaborated elsewhere (ibid.).

II. Variable Measurement

With an in-depth omnibus survey instrument implemented by Vietnamese interviewers in the homes of respondents (see https://vhas.utah.edu/_resources/documents/vhas-questionnaire- english.pdf), the VHAS provides detailed data on respondents’ life history experiences and exposures during wartime, their family background and migration history, as well as a breadth of information on current health conditions and health behavior, income and assets, household composition and family relationships, and social connections and support. The VHAS is unique in its combination of early life war exposure and late life health data for leveraging analyses of armed conflict’s lasting consequences for health and aging.

i. Dependent Variable

We assess our dependent variable, insomnia severity, using an ordered categorical variable. The variable is based upon participants’ self-reported experience of insomnia in the past month, characterized as none, moderate, or severe.

ii. Independent Variables

We construct four sets of independent variables in order to examine the extent and pathways through which early life experiences of war impact upon insomnia in late life. These variables capture early life stressors linked to one’s social positioning in the war, as well as more proximate stress and health conditions known to exacerbate sleep problems. Our first measure of wartime stress exposure is based upon respondents’ military service, in particular whether they served in the formal military (e.g., the People’s Army of Vietnam), an informal military organization (e.g., a paramilitary/militia unit such as the Youth Shock Brigades), or did not complete any military service. We round out our assessment of wartime stressors with two standardized indices assessing respondents’ exposure to a series of war-related combat and violence exposures (e.g., their own injury in wartime, having seen dead Vietnamese or foreign soldiers), and their experience of a series of malevolent environmental conditions during war (e.g., having to flee due to bombing, severe wartime shortages of food or water, the persistent fear of death, and exposure to toxic chemicals like Agent Orange). Details on the methods and component items utilized to construct the standardized war exposure indices are reported elsewhere (Young et al. 2021).

Next, in light of past research highlighting associations among trauma, PTSD, and insomnia, we employ a categorical variable capturing recent PTSD symptom severity reported by VHAS respondents. The VHAS includes nine questions drawn from the 20-item PTSD Checklist (PCL-5), covering each of the four diagnostic clusters for PTSD—reexperiencing, avoidance, dysphoria, and hyperarousal (Price et al. 2016). These items query whether, in the last month, the respondent had experienced (1) repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of a stressful wartime experience; (2) strong physical reactions when something reminds them of the experience; (3) avoidance of memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the experience; (4) strong negative beliefs about themselves, other people, or the world; (5) loss of interest in activities they used to enjoy; (6) irritable behavior, angry outbursts, or aggression; (7) feeling jumpy or easily startled; (8) difficulty concentrating; (9) or trouble falling or staying asleep. Items were scored from 0 to 3, capturing whether respondents had experienced a symptom and whether it bothered them not at all, a little bit, moderately, or a lot. We removed the final item, trouble falling/staying asleep, from the calculation of PTSD symptom severity due to the close association (r=0.364) with our dependent variable. We generate PTSD symptom levels – None, A few symptoms, Subclinical, or provisional PTSD — based upon percentage cut-points specified by the VA for the 20-item (48 point) PCL and modified for use with our 8-item (24 point) index. Our cut-point threshold for provisional PTSD (>=10) also considers the underreporting of mental health conditions in Vietnamese culture (for more on this see: Kovnick, et al. 2021; Nguyen 2015; van der Ham et al. 2011; Vuong et al. 2011).

We also incorporate into the models a set of recent stressful life events that we hypothesize will exacerbate insomnia. These indices, which we have standardized on a 0-3 point scale, comprise family-related stressors, recent personal event stressors, and financial stressors. Some of the stressors included in the indices are based on questions about martial disruptions, recent deaths in the family, illnesses experienced by family members, accidents that caused physical or psychological harm, major residential moves, and great financial difficulties.

As indicators of health conditions which pertain to insomnia severity we include a categorical variable indicating whether the respondent indicates having experienced bodily pain, and the degree of pain (whether slight, moderate or severe). Physical exercise is also assessed categorically, and is coded as having participated in no physical exercise in the past year, infrequent physical exercise (monthly-less than weekly), or frequent physical activity (daily or almost daily). As an additional marker of health, we have assessed respondents’ level of frailty, assessed categorically as “not frail,” “very mildly frail,” “mildly frail,” and “moderately/severely frail.”

iii. Control Variables

Finally, our models incorporate a series of socioeconomic and demographic control variables, namely respondent’s age, sex, district of residence, current marital status, current working status, and educational attainment.

III. Analytical approach

In addition to univariate and bivariate statistics, we estimate nested survey-adjusted generalized ordered logit models in order to examine the associations between variables. We utilize the generalized ordered logit estimation (gologit2) due to a violation of the proportional odds assumption observed for the full model when utilizing ordered logit (ologit) estimation. Through a process of listwise deletion we arrive at an analytical sample size of 2,327. We use Stata 16.1 for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

I. Sample Descriptive Statistics

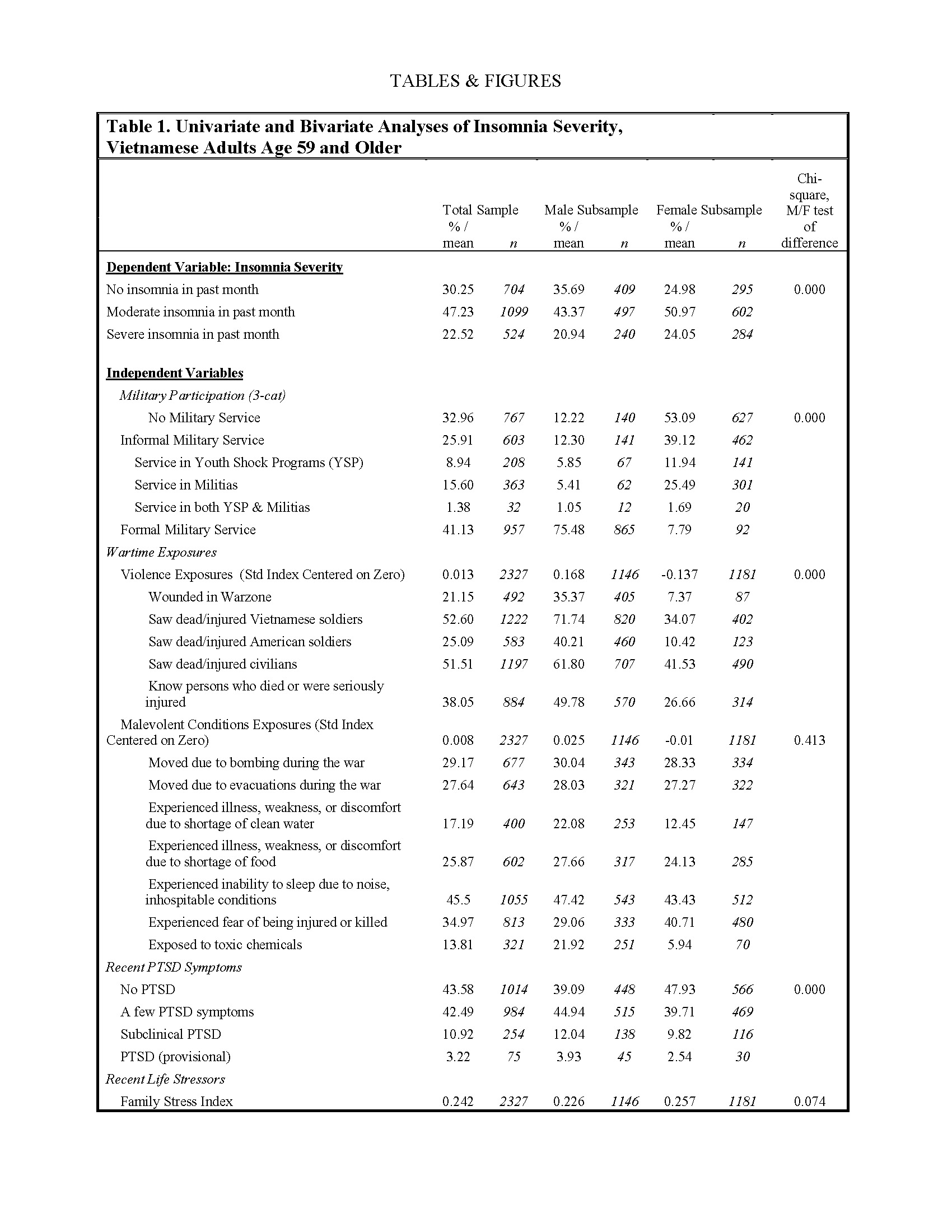

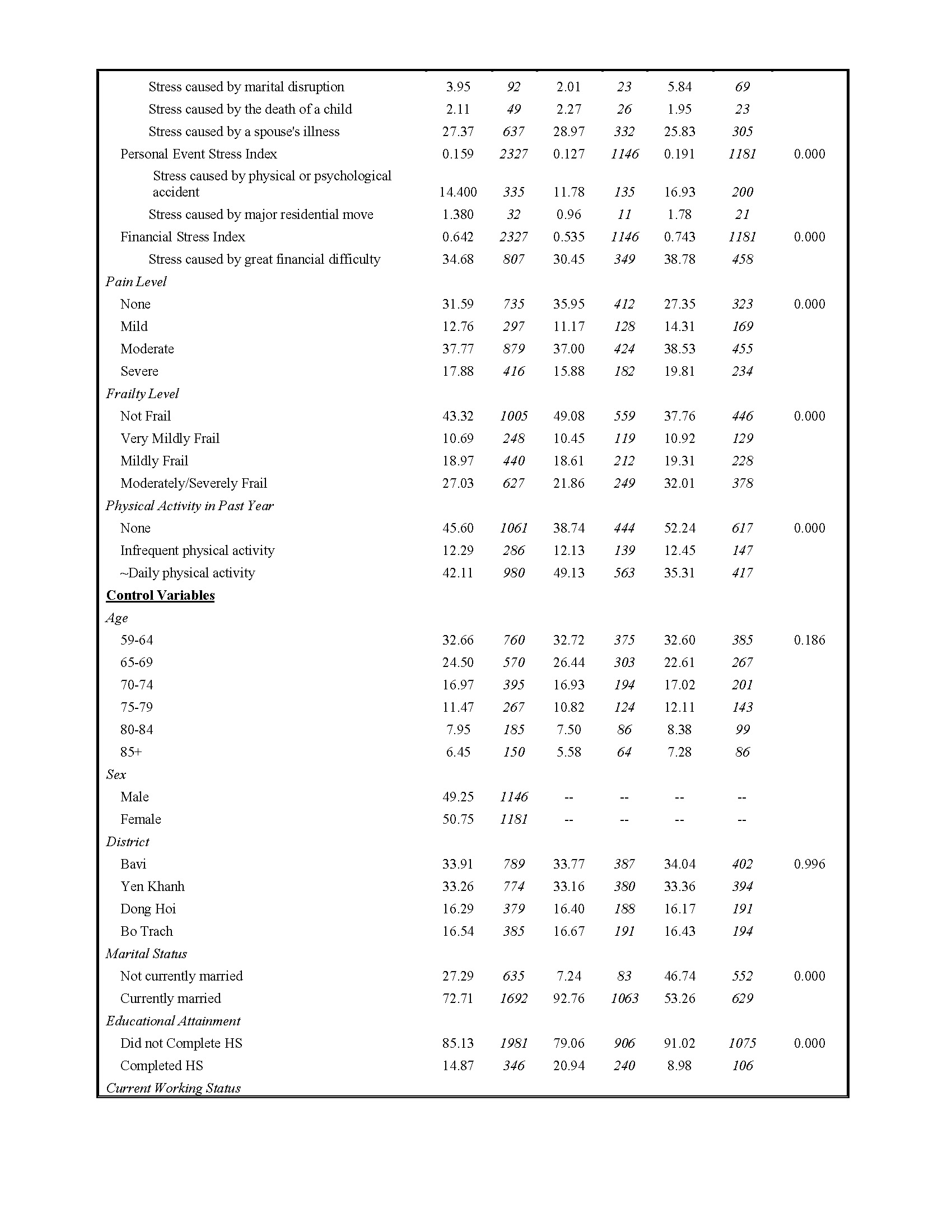

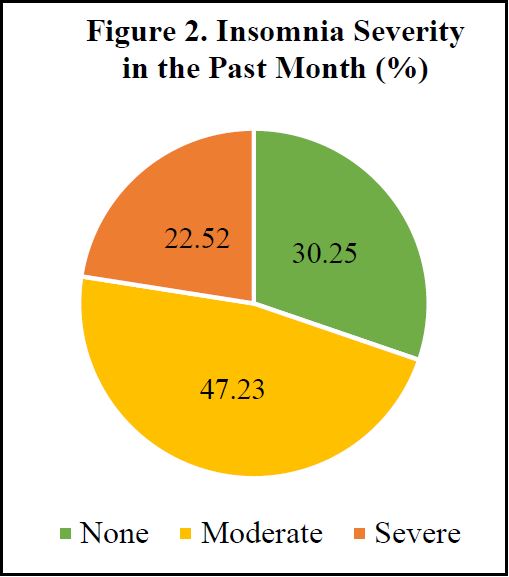

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for our full analytical sample, as well as for subsamples of men and women. Descriptive data are unweighted and are presented as percentages or mean values, as appropriate. Our descriptive results demonstrate that insomnia, including severe insomnia, is relatively common within the VHAS sample.

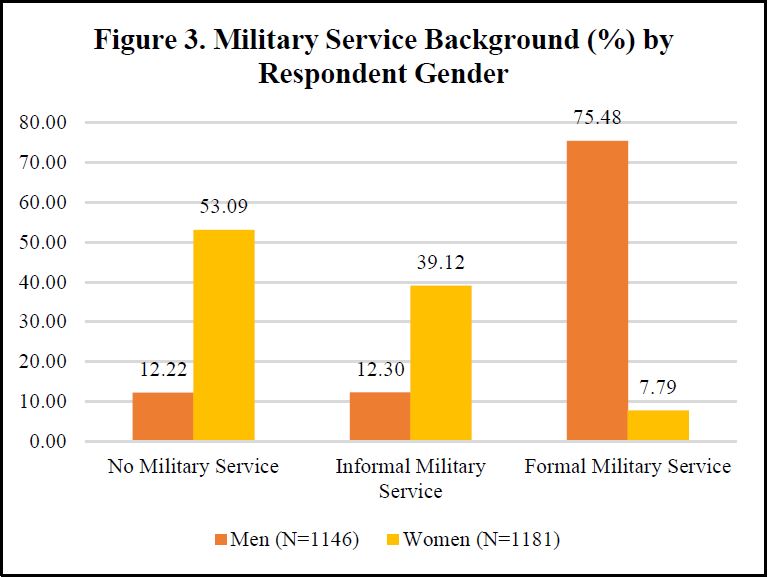

Moreover, women exhibit a greater prevalence of both moderate and severe insomnia compared to men. With respect to our independent variables, high levels of lifetime military service, with approximately two-thirds of the sample indicating either formal or informal service, are in part reflective of military mobilization in the DRV during respondents’ youth, but more so a reflection of VHAS subdomain sampling in military service and gender categories. That said, over three-quarters of men in the VHAS sample served in the formal military. A significant minority of women in the sample also served in formal military roles (7.79%), while nearly 40% served in informal military roles, largely as volunteers in the Youth Shock Brigades.

Wartime violence exposures are assessed by standardized indices, centered around zero, thus challenging univariate description. We do observe that men’s mean violence exposure index is significantly greater than that of women, while the gender difference in malevolent conditions exposure is statistically insignificant. Likely a reflection of their different military service roles and distinctive degrees of violent stress exposures in wartime, men and women diverge in their levels of recent PTSD symptoms. Specifically, women are more likely than men to indicate experiencing no recent PTSD symptoms, while men exhibit higher symptom severity consistent with subclinical PTSD and PTSD (provisional).

Life event stressors are also standardized indices which suggest that financial stress is the most prevalent stressor in the VHAS sample, followed by family stressors and personal event stressors. Women report slightly greater levels of family stress than men, and levels of personal event and financial stress that are significantly greater than men. With respect to late life health conditions, we see that significant shares of the VHAS sample suffer from bodily pain, including severe pain (17.88%), with reported degrees of pain greater among women than men. Physical exercise frequency exhibits a bimodal pattern, with a sizable share (45.6%) indicating having done no/almost no physical activity in the past year, and a nearly parallel share (42.11%) indicate having done physical exercise daily/almost daily. Men in the VHAS sample are significantly more likely than women to report daily/almost daily physical activity. We have also observed that about half (50%) of our sample experiences some level of frailty, and roughly 27% experience moderate to severe frailty. This quality is overrepresented in women, and 32% of the women in this sample experience moderate to severe frailty.

Rounding out our descriptive statistics, we see that nearly three-quarters of the analytical sample is currently married, but women are far less likely to be currently married. Less than 15% completed high school education, and a significantly smaller share of women (8.98%) have this education credential. Many in the sample remain economically active, despite their older ages. Specifically, nearly one half of the sample reports they are currently working for pay/profit.

II. Bivariate Analyses

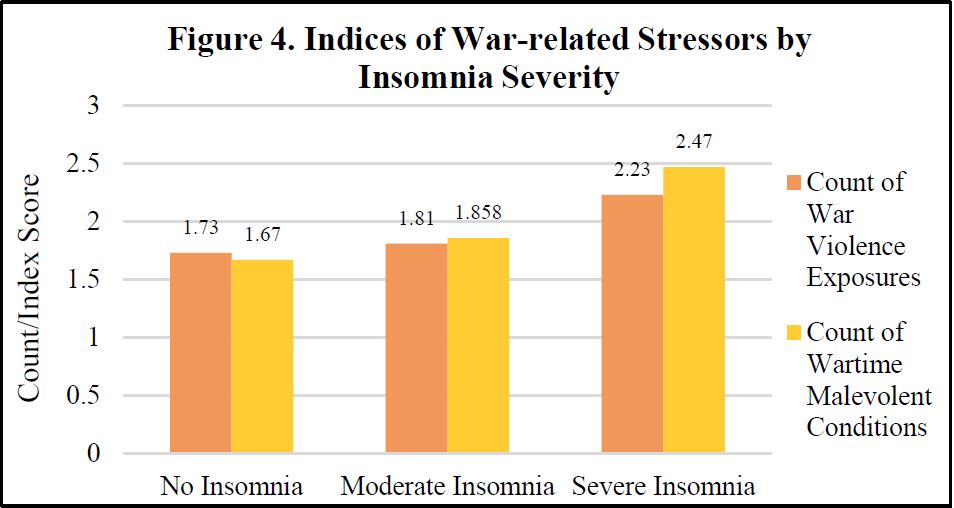

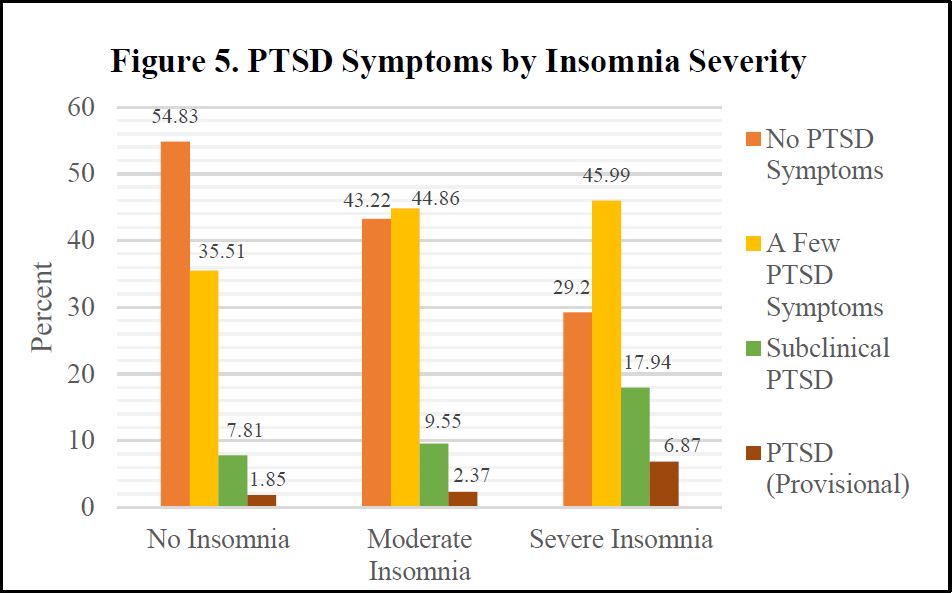

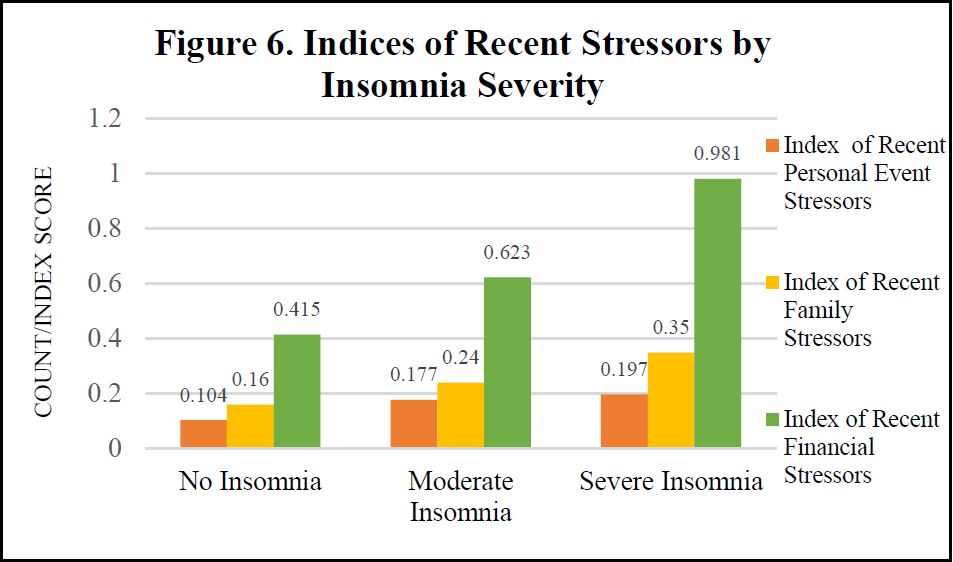

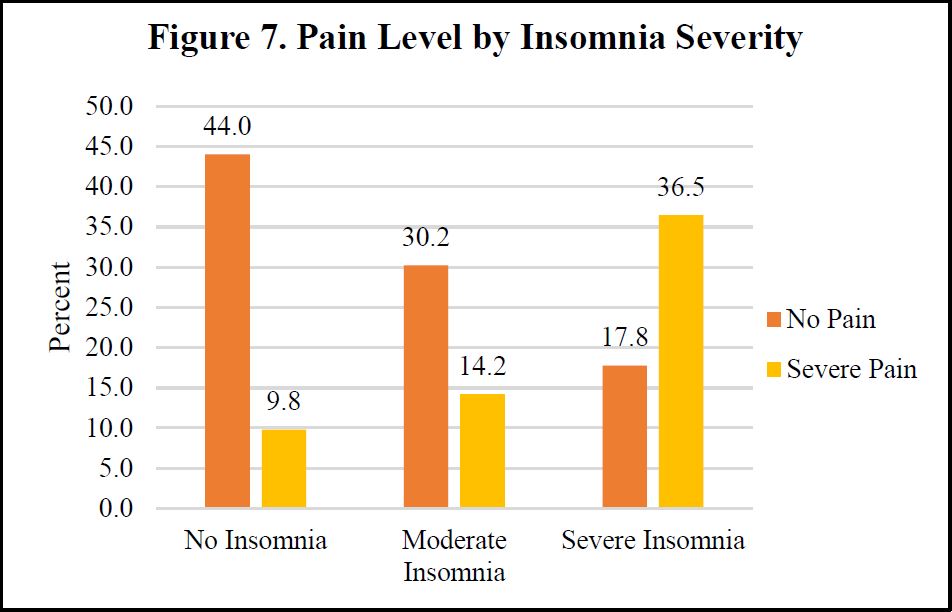

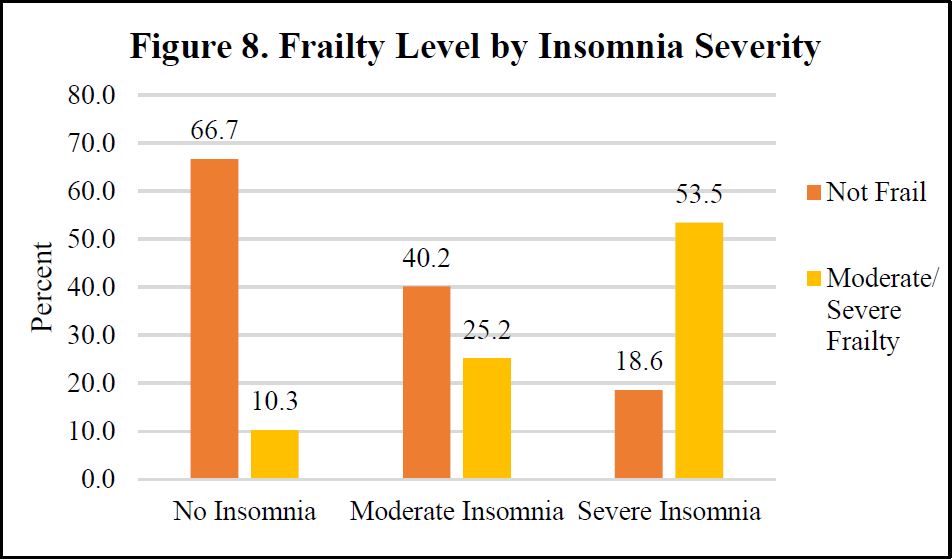

We display select bivariate analyses in Figures 4-8, depicting bivariate associations between insomnia and war stress exposures, PTSD Symptom severity, recent life event stressors, pain and frailty level, respectively. Across each of these independent variables, consistent with hypothesized associations, we observe a positive association with insomnia severity. Those with more severe stress exposure during war, worse PTSD, more frequent and severe recent life stressors, worse pain and more frailty exhibit more severe insomnia.

III. MultivariateModelResults

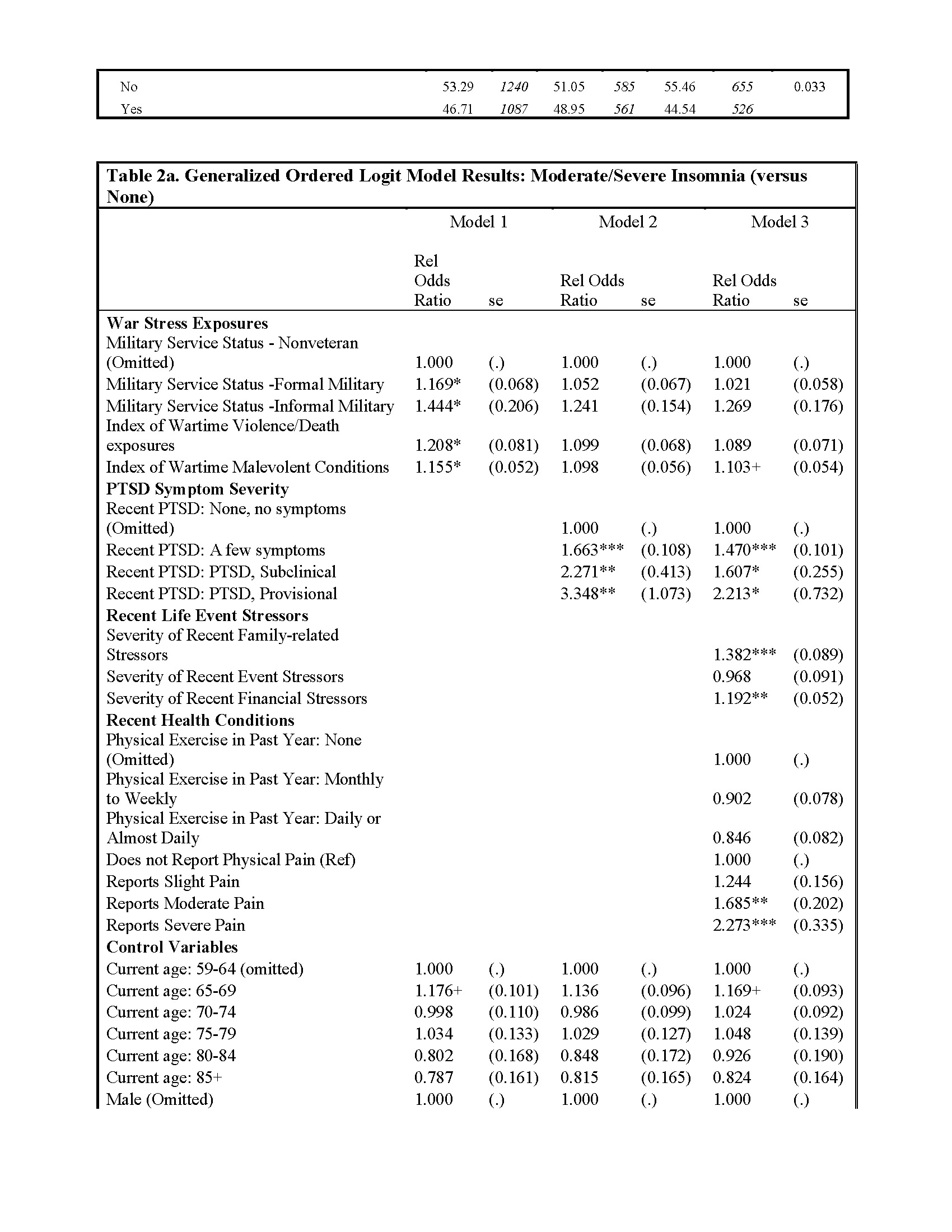

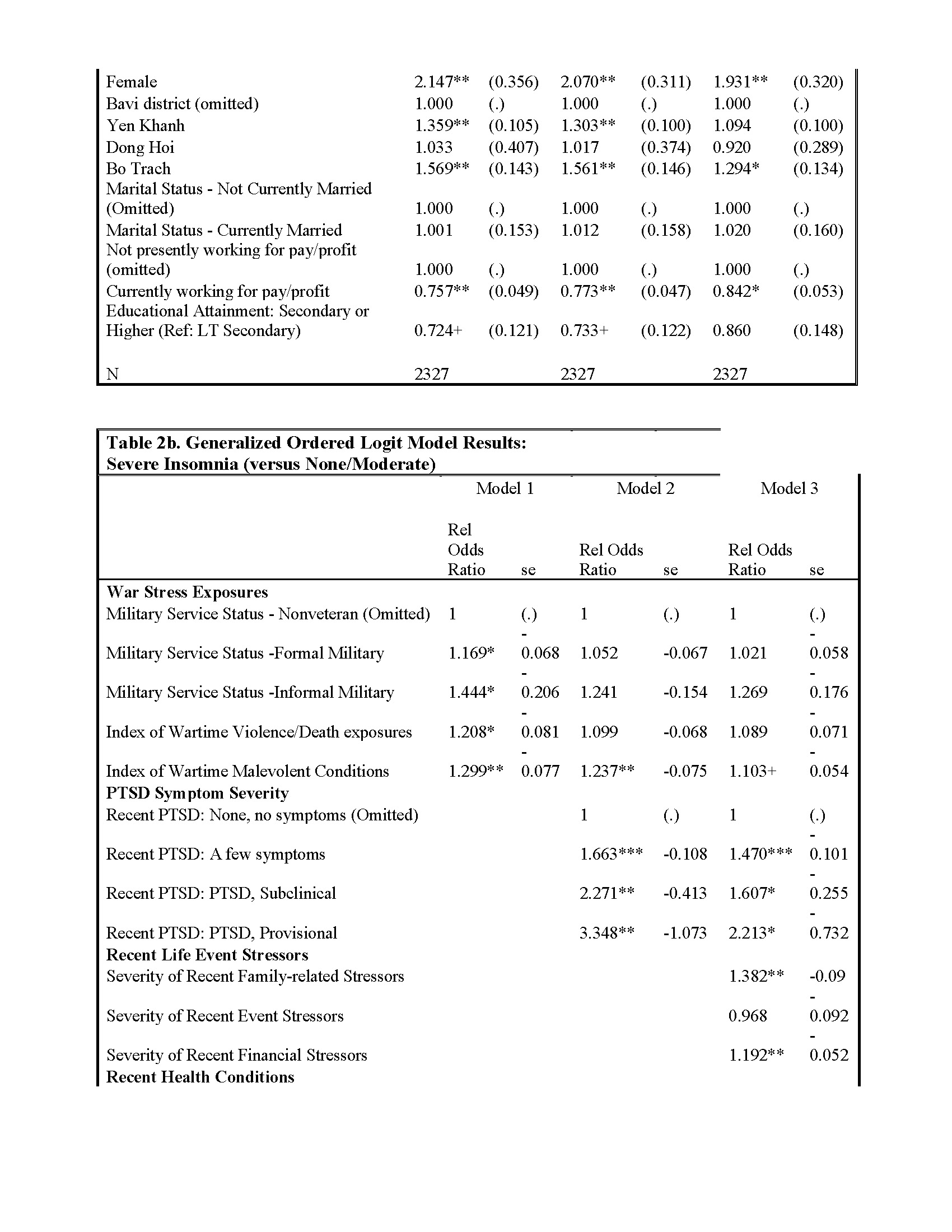

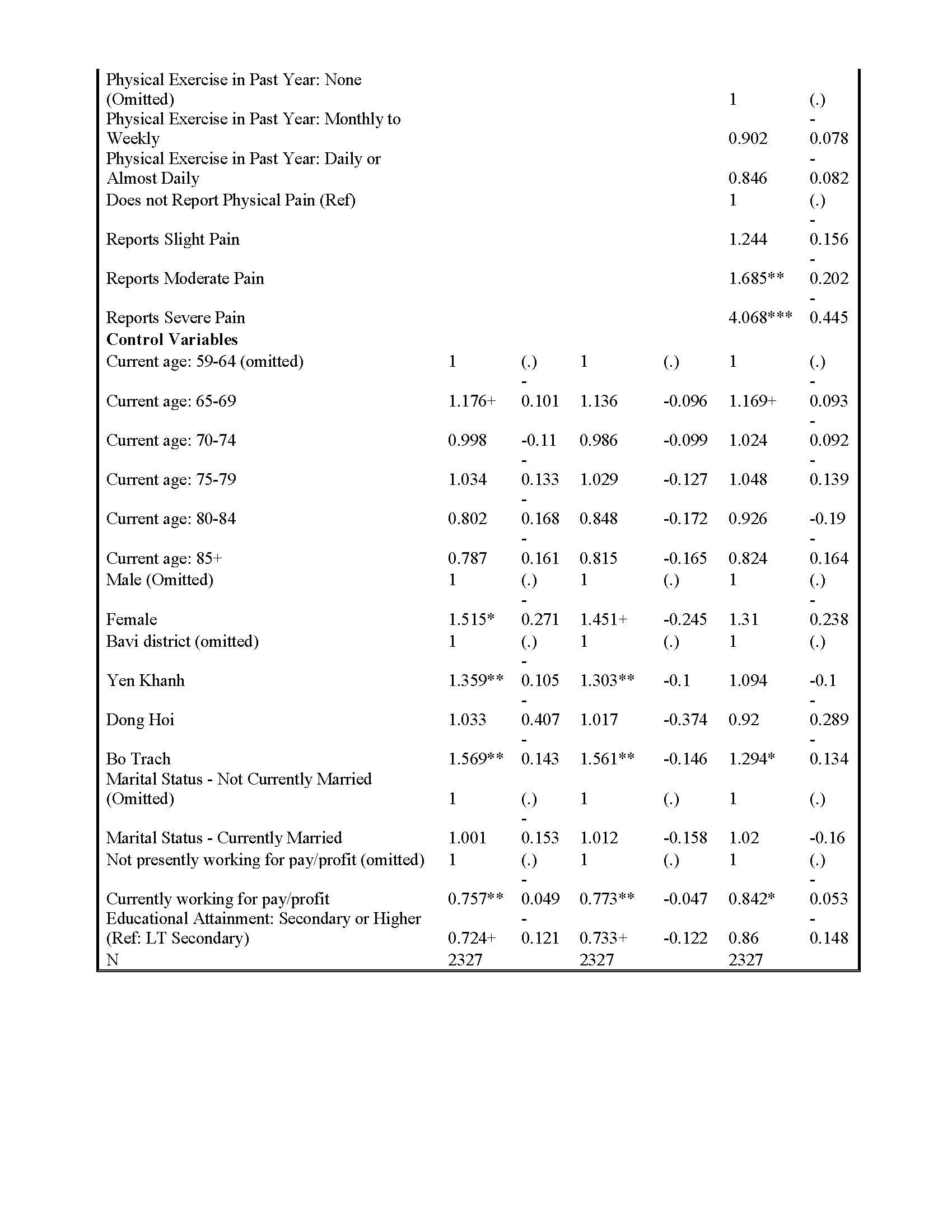

We report the results of three sets of generalized ordered logit regression results and standard errors in Tables 2a and 2b. Table 2a includes relative odds ratios (exponentiated logit coefficients) for moderate and severe insomnia combined, with no insomnia as the reference category. Table 2b provides relative odds ratios (exponentiated logit coefficients) for severe insomnia, with reference to moderate and no insomnia combined. In both tables, Model 1 includes military service and a series of covariates. Model 2 incorporates our two war-related stressor indices. Model 3 adds recent life event stressors and health conditions pertinent to insomnia, in particular PTSD and reported regular suffering from physical pain. Because the direction and magnitude of results are largely consistent across Tables 2a and 2b, we concentrate our discussion upon the results, as they relate to our study hypotheses, contained in Table 2a.

The multivariate results in Table 2a are largely consistent with our hypotheses concerning war-related stressors in early life and late life insomnia severity. First, consistent with our first two hypotheses, the generalized ordered logit regression results indicate that war stress exposures, including both military service and indices of violence and malevolent conditions in wartime, each heighten the risk of insomnia among Vietnamese older adults in the analytical sample. However, consistent with our third hypothesis, these war stress exposures are largely attenuated when we incorporate recent PTSD symptom severity into the models.

Older adults’ recent experiences of life event stressors, especially family-related stressors (e.g., divorce, the death of a child) and financial stressors, result in heightened risk of insomnia relative to those with fewer/less severe stressful life events. And our hypothesized associations between recent health conditions and insomnia are partially supported in Model 3. Specifically, older adults reporting moderate and severe bodily pain are significantly more likely to experience insomnia than their pain-free counterparts. We observe no significant association between recent physical activity frequency and insomnia.

In sum, war exposures experienced decades prior, in early adulthood, are relevant to the experience of insomnia among Vietnamese older adults who experienced wide-ranging and diverse wartime stressors in their youth. However, the attenuation of war stress exposure coefficients to statistical insignificance in the second and final model suggests mediating pathways between war stress exposure and insomnia via more proximate health conditions and stressors. Moreover, those who continue to suffer from symptoms of PTSD linked to the hardships and stressors of war are at particular risk for insomnia.

DISCUSSION

The enduring toll of war can be observed far past its immediate casualties, in the morbidities and causes of death among those most negatively impacted by wartime violence. The physical and mental health of those who have been exposed to war can persist for decades. Sleep disorder is a critical domain within which the lasting traumas of war may be apparent, and where war’s stressors may deliver ongoing assaults to late life physical health and cognitive functioning. This study extends and supplements this research by finding significant correlations between military service, wartime exposures and later-life insomnia. Through this examination, we are able to foster a greater understanding of the temporality of war and its long-term impact on the sleep quality of the Vietnamese war era cohort.

Our results are suggestive of processes extending from early life stressors in wartime to poorer sleep, as assessed by recent insomnia. Importantly, the experience of proximate physical and mental health conditions appear as key mediators between early life stress in war and late life insomnia. These mediating pathways are suggestive of treatments, such as pain relief, strength training, and mental health counseling, that may alleviate the long-term scars of war and thereby aid in improving sleep quality in those who suffered the greatest levels of stress during wartime. Advocates of such treatments point to various methods that target pain, recent PTSD, and sleep disturbances collectively, including narrative exposure therapy, eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing, self-managing skills development, and low-dose NSAIDs (Lies, Jones & Ho, 2019). By taking a comprehensive approach to addressing the long-term impact of war on sleep quality, we can help to alleviate its enduring legacy and support individuals in their pursuit of health and wellbeing.

Despite the many strengths of our study, several limitations warrant mention. The VHAS is limited in its sampling and attrition rates, and generalizing our results may contribute to biased conclusions about the current health status of our participants. One example of this limitation is that our study could only include surviving older Vietnamese adults, preventing us from studying the impact of war exposure among those killed during the war or who have died since the war ended. This selective mortality within this war era cohort may dampen the associations between war exposures and later-life health. Furthermore, our main dependent variable relied on one question assessed in participants by self-report questionnaire. Although this variable was adapted from validated self-report measures, it was not verified by biometric calculations or actigraphy and the question itself may be interpreted differently based on the participants’ understanding of insomnia. To remedy this limitation, further studies could include a broader range of questions addressing sleep quality and insomnia, along with a detailed clinical assessment of sleep quality to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

This study is only the beginning of a larger, cross-sectional examination of sleep quality among Vietnamese older adults. The VHAS recently finished collecting its second wave of data in 2022, and its self-report questionnaires were revised to include additional recent sleep measures. Some examples of questions asked of the participants in Wave 2 include:

i. “Have you experienced insomnia in the last month?”

ii. “In the past month, how many hours and minutes did you approximately sleep on a weeknight?”

iii. “In the past month, did you sleep badly?”

The VHAS longitudinal approach, which repeats assessments of physical and mental health status at two time points (2018 and 2022), permits analyses of changes in health linked to disordered sleep. Further studies should compare prevalence and predictors of insomnia in other post-conflict populations to obtain a more complete understanding of the legacies of war on health and aging.

In conclusion, analyses of Vietnam’s cohort of older adult war survivors yields new evidence on the myriad ways that war may increase later-life insomnia risk, and more broadly, the global burden of disease. Vietnam is not alone among LMICs undergoing struggles of economic development while also providing healthcare services to a generation of older adults whose lives were deeply affected by war. The current study takes an important step toward addressing the linkages between specific, individual-level war exposures and later-life insomnia, allowing clearer identification of groups who may benefit from treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

DISCLOSURE STATEMENTThe content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research is not industry supported and the authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Appy, C. (2003). Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides. Penguin Group.

Armenta, R. F., et al. (2018). Factors associated with persistent posttraumatic stress disorder among U.S. military service members and veterans. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1590-5

Bombois, S., et al. (2010). Sleep disorders in aging and dementia. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 14(3), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-010-0052-7

Endeshaw, Y. (2012). Aging, Subjective Sleep Quality, and Health Status: The Global Picture.

Sleep, 35(8), 1035–1036. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1984

Ferraro, K. F., Shippee, T. P., & Schafer, M. H. (2009). Cumulative inequality theory for research on aging and the life course.Gehrman, P., et al. (20160. PTSD and Sleep. PTSD Research Quarterly, 27(4), ISSN: 1050-1835. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V27N4.pdf .

Gehrman, P., et al. (20160. PTSD and Sleep. PTSD Research Quarterly, 27(4), ISSN: 1050- 1835. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V27N4.pdf .

Gildner, T. E., et al. Associations between Sleep Duration, Sleep Quality, and Cognitive Test Performance among Older Adults from Six Middle Income Countries: Results from the Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 10(06), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3782.

Grandner, M. A. (2017). Sleep, Health, and Society. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 12(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2016.10.012.

Guillemot, F. (2009). Death and Suffering at First Hand: Youth Shock Brigades during the Vietnam War (1950–1975). Journal of Vietnamese Studies, 4(3), 17–60. https://doi.org/10.1525/vs.2009.4.3.17.

Hirschman, C., Preston, S., & Loi, V. M. (1995). Vietnamese casualties during the American war: A new estimate. Population and Development Review, 21(4), 783–813.

Korinek, K., et al. (2019). Design and measurement in a study of war exposure, health, and aging: protocol for the Vietnam health and aging study. BMC Public Health 19, 1351.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7680-6

Korinek, K., et al. (2020). Is war hard on the heart? Gender, wartime stress and late life cardiovascular conditions in a population of Vietnamese older adults. Social Science & Medicine, 265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113380.

Kovnick, M. O., et al. (2021). The Impact of Early Life War Exposure on Mental Health among Older Adults in Northern and Central Vietnam. Journal of health and social behavior, 62(4), 526–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465211039239.

Kripke, D. F., Simons, R. N., Garfinkel, L., & Hammond, E. C. (1979). Short and long sleep

and sleeping pills. Is increased mortality associated? Archives of General Psychiatry, 36(1), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780010109014

Kwon, H. (2012). Rethinking traumas of war. South East Asia Research, 20(2), 227–237. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23752539

Laderman, S., & Martini, E. A. (Eds.). (2013). Four Decades On: Vietnam, the United States, and the Legacies of the Second Indochina War. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11qdz12

Leeming, M. (2015). Review of Agent Orange: History, Science, and the Politics of Uncertainty, by E. Martini. Environment and History, 21(1), 165–167. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43299723

Lies, J., Jones, L., & Ho, R. (2019). The management of post-traumatic stress disorder and associated pain and sleep disturbance in refugees. BJPsych Advances, 25(3), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2019.7

Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S134864

Miguel, E., & Roland, G. (2011). The long-run impact of bombing Vietnam. Journal of Development Economics, 96(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.07.004.

Nguyen, H. T. (2017, January 17). Opinion | As the Earth Shook, They Stood Firm. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/17/opinion/as-the-earth-shook-they-stood- firm.html

Shepard, J. W., et al. (2005). History of the Development of Sleep Medicine in the United States. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 1(1), 61–82.

Simonelli, G., et al. (2018). Sleep health epidemiology in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of poor sleep quality and sleep duration. Sleep Health, 4(3), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.03.001

Stranges, S., et al. (2012). Sleep Problems: An Emerging Global Epidemic? Findings From the In Depth WHO-SAGE Study Among More Than 40,000 Older Adults From 8 Countries Across Africa and Asia. Sleep, 35(8), 1173-1181. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.2012.

Watson, N., et al. (2015). Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: Methodology and Discussion. Sleep, 38(8), 1161-1183. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4886.

Zimmer, Z., et al. (2021a). War across the life course: examining the impact of exposure to conflict on a comprehensive inventory of health measures in an aging Vietnamese population, International Journal of Epidemiology, 50,(3), 866–879. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa247.

Zimmer, Z., et al. (2021b). Early-Life War Exposure and Later-Life Frailty Among Older Adults in Vietnam: Does War Hasten Aging?, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, gbab190, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbab190.