College of Education

13 What Should the Main Roles of Public Elementary Education Be in the United States? An Exploratory Study Based on Survey Responses of Teachers During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Tessa Cahoon

Faculty Mentor: Mary Burbank (Education, Culture & Society)

Introduction

Education is an important value in American society. Public schools are expected to fill many spoken and unspoken roles in our society. These roles range from teaching academics and preparing students for the workforce to teaching English, providing food for low-income students, keeping students safe, and meeting the individual needs of all students, including those with disabilities (Spring 2018).

During the 2020-21 school year, COVID-19 put a significant strain on the public education system. Teachers were forced to take on more responsibilities, all within a context of limited resources and extra challenges (both personal and public). They also had to adapt quickly to new conditions and expectations as well as re-evaluate their teaching priorities (Arnett, 2021). Thus, this was an opportune time to revisit what we expect from our schools and to assess how realistic our expectations are, particularly since education continually faces new challenges and changing needs and demographics.

Methods

An online survey was sent out to seven elementary schools in City View District (a pseudonym). Data were gathered in accordance with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. Teachers were asked about how effective they were at meeting a list of seven expectations based on the 2013 Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (InTASC) and the Utah Effective Teaching Standards (UETS). Additionally, teachers were asked how COVID-19 affected their ability to meet these expectations and how their school and community prioritized these expectations. The survey’s open-ended questions were analyzed quantitatively by grouping responses into themes and categories, and the survey’s close-ended questions were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

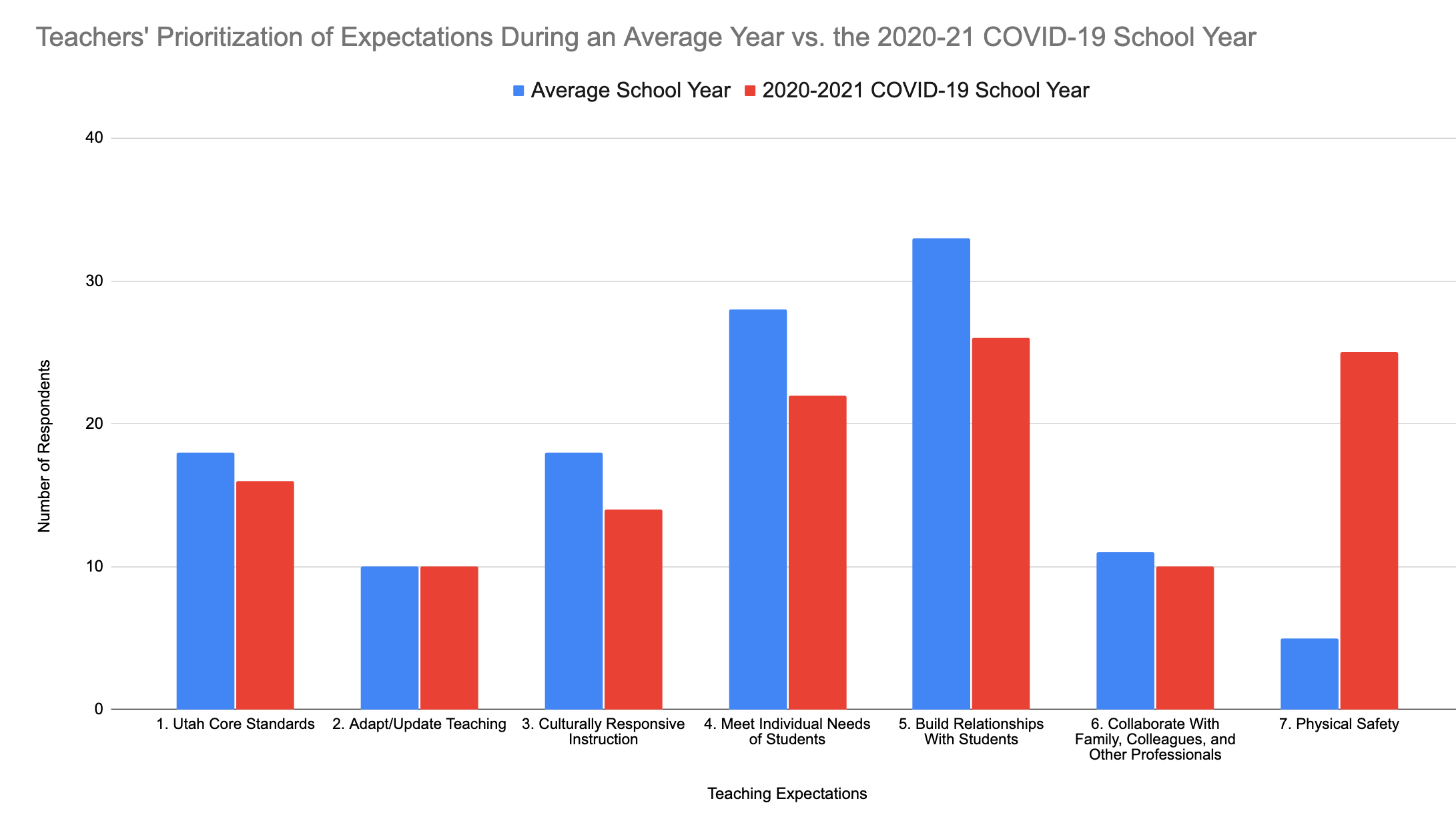

- During an average school year, teachers’ top four priorities were building relationships with students, meeting the individual needs of all students, teaching the Utah Core Standards and providing culturally responsive instruction. Teacher priorities remained consistent during the 2020-21 COVID-19 year, with the unsurprising exception that physical safety tied with building relationships with students for the top priority.

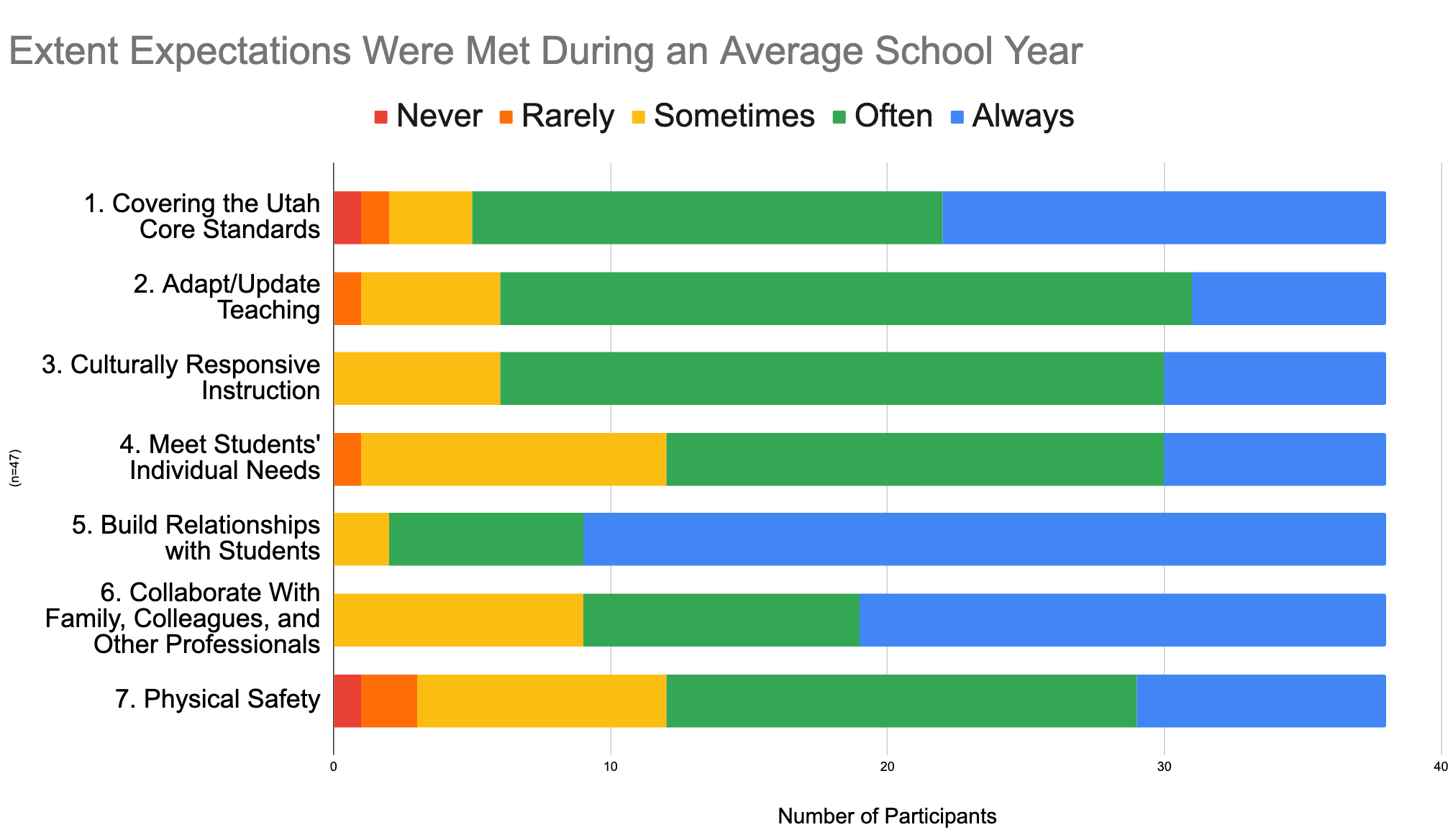

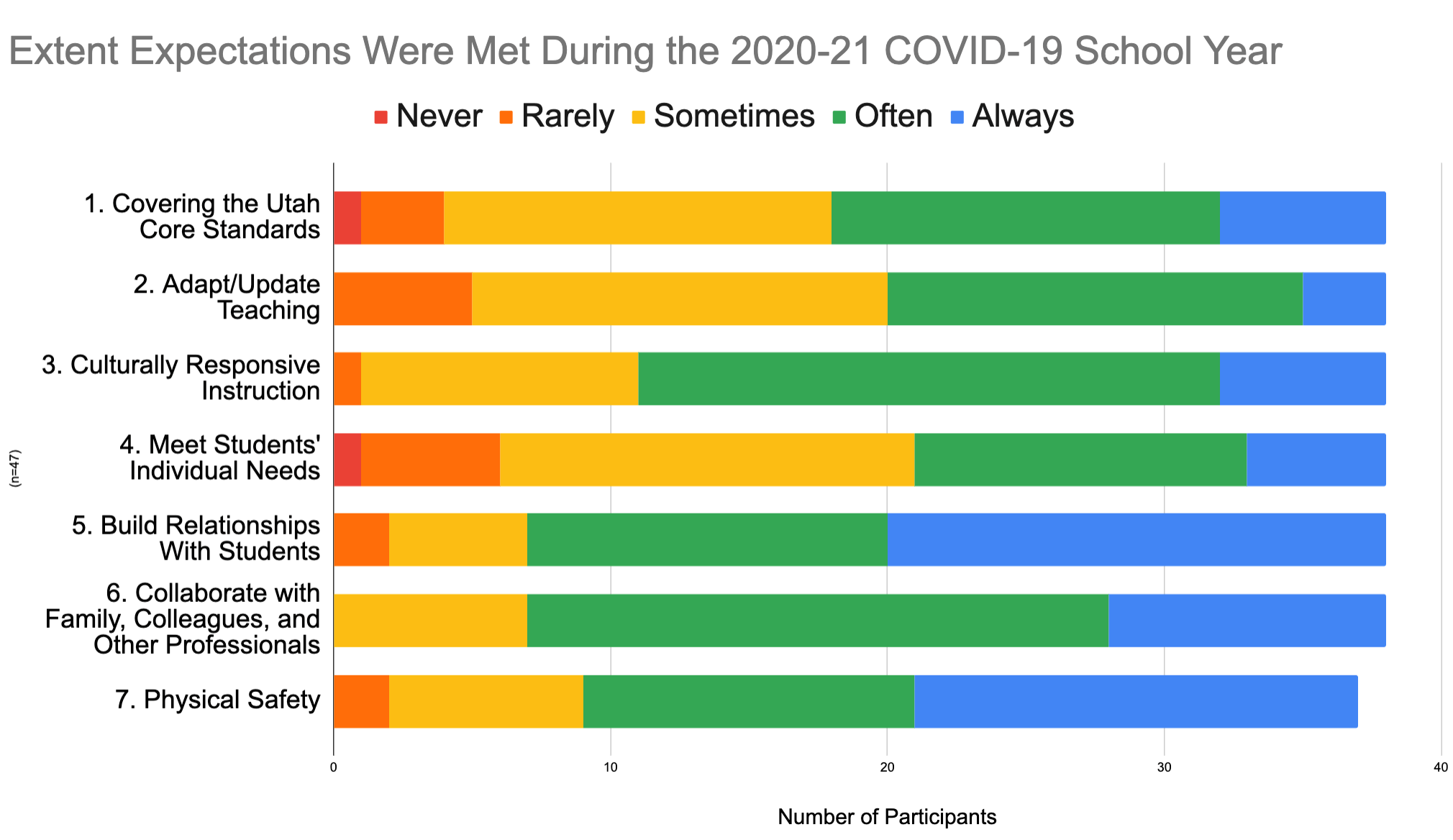

- Teachers’ ability to meet expectations matched their top four priorities, with one big exception: meeting the individual needs of all students. Only 68% of teachers felt they could meet this expectation during an average year; during the 2020-21 school year, this dropped to 45%.

- The COVID-19 pandemic made it more challenging for teachers to meet the majority of the expectations; however, the most marked declines were meeting the Utah Core Standards and adapting/updating teaching instruction.

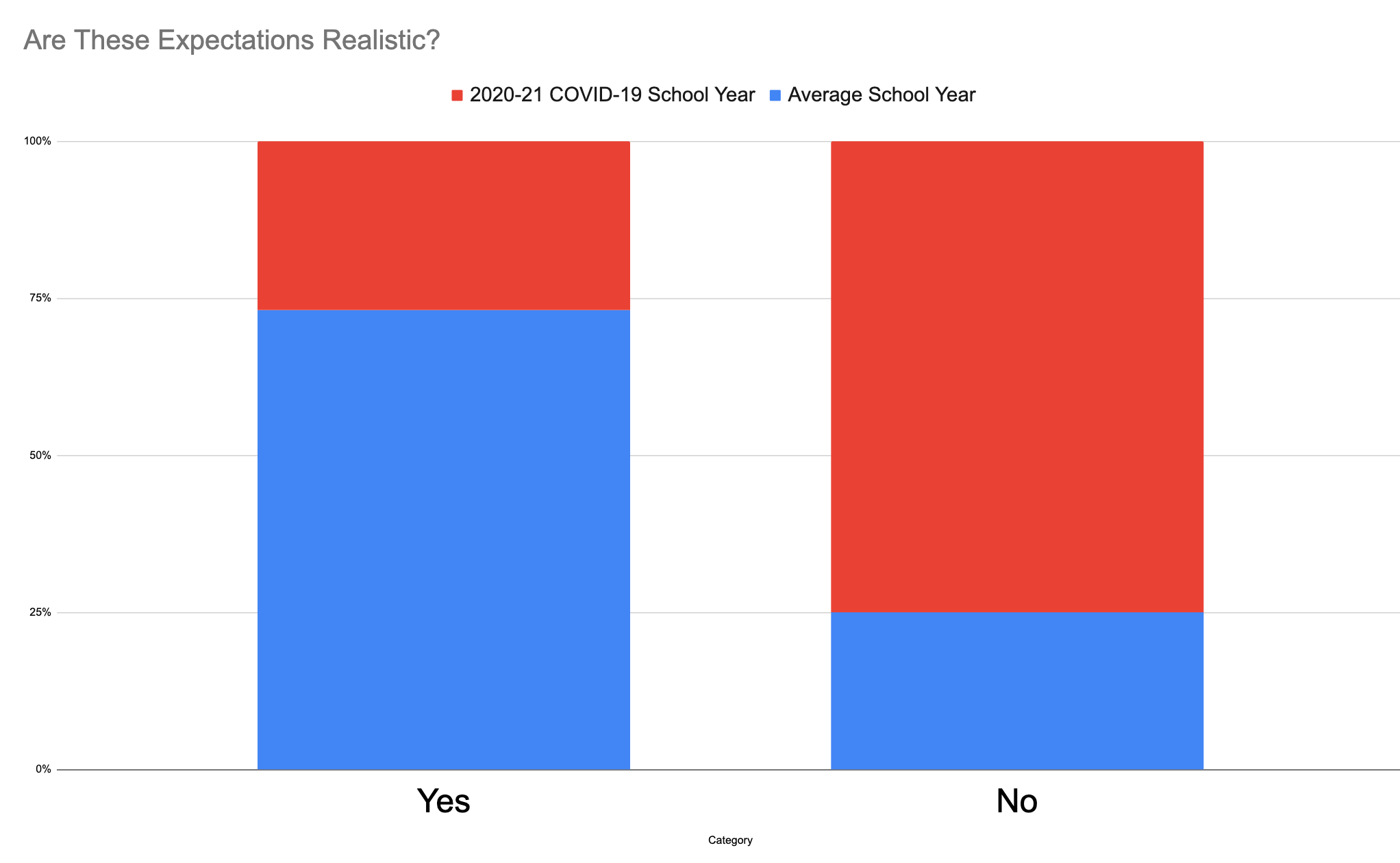

- 76% of respondents felt that teaching expectations were realistic in an average school year, but this dropped steeply to 28% during the 2020-21 school year. However, even during an average year, 24% of teachers felt expectations were unrealistic.

- Respondents reported needing more support in meeting the academic and mental health needs of students and in providing students with differentiated instruction. Respondents also reported needing better mental health support and better financial compensation for themselves.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic undeniably made public education more challenging during the 2020-21 school year; however, teachers were already struggling to meet all of the expectations placed upon them before the pandemic. As a nation, we need to have important conversations about what we really value and expect from our teachers. Teachers need more support and resources in order to effectively fulfill their teaching responsibilities, particularly as the needs of students become more diverse and teaching conditions continue to be complex and challenging.

References

Arnett, T. (2021, January). Breaking the mold: How a global pandemic unlocks innovation in K-12 instruction. Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation. https://www.christenseninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BL-Survey-1.07.21.pdf

Council of Chief State School Officers. (2013, April). InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards and Learning Progressions for Teachers 1.0. https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/2013_INTASC_Learning_Progressions_for_Teachers.pdf

Spring, J. H. (2018). American education (18th ed.). Routledge.

Dupree, K. M., & Hill, K. (2013). Utah Effective Teaching Standards and Indicators. https://www.schools.utah.gov/file/7313cfe5-5e68-41ef-9de4-03e5a9d395d8

Figure 1. Teachers’ Prioritization of Expectations During an Average Year vs. the 2020–21 COVID–19

School Year

Figure 2. Extent Expectations Were Met During an Average School Year

Figure 3. Extent Expectations Were Met During the 2020–21 COVID–19 School Year

Figure 4. Are These Expectations Realistic?