College of Engineering

23 Disabled, Not Disqualified: Ableism in Recruitment and Retention in Game Development

Will Loxley

Faculty Mentors: Fernando Rodríguez and Ashley Guajardo (Entertainment Arts Engineering, University of Utah)

Abstract

Game development careers are widely regarded as turbulent due to a fiercely competitive barrier of entry and industry reliance on harmful labor practices. Periods of compulsory overtime known as crunch plague professional game developers, while prospective developers seeking entry-level employment are challenged by a critical lack of transparency from game companies. And despite disabled individuals being especially vulnerable to discrimination from recruitment and retention practices, the practical experiences of disabled game developers both in-and-outside the industry are significantly underexplored.

This paper documents how AAA game companies publicly and actively recruit disabled people as candidates for the next generation of the games industry – if at all. An institutional ethnography is conducted to investigate if game company recruitment efforts operate under the incorrect assumption that recruitment is an inherently neutral or objective practice. The research centers disabled game developers through the inductive thematic analysis of 20 AAA game companies’ public facing documentation via document analysis to determine if disabled people are excluded from being talent recruitment.

Game companies are found to disregard disabled candidates in recruitment efforts and public facing documentation exhibits a low level of support for disabled professional game developers. The results suggest high-level improvements for online game company recruitment practices so as to better represent internal values and diversify the potential pool of applicants. The results also inform future research on inclusive hiring programs and identifying industry norms which negatively affect recruitment and retention for disabled game developers.

Background

Game development is a “creative collaborative practice” (O’Donnell 2014) in which technical and creative disciplines regularly interact to deliver a minimum viable product, often under extreme project management constraints. “Triple-A” (AAA) is the conventional face of game development, as AAA games are typically regarded as blockbusters due to consistently high levels of popularity. The disciplines involved in development are progressively refined as new cohorts of game developers (GD) attempt to improve and remain active in the industry, despite the uniquely paced and passion-oriented organization of work (Cote & Harris 2021; Taylor 2006). Maintaining GD careers is thus vital to the overall health of such a high-commitment and high-involvement industry (Weststar & Legault 2017), particularly for underemployed communities.

Although several historically marginalized communities qualify as underemployed in the games industry, the overwhelming majority of research in games spaces directed toward disability pertains to disabled users, or players, in the form of frontend digital accessibility. Further, research on equitable product design and digital games labor has trended toward focusing on non-disabled working lives, whether intentionally or otherwise. This has resulted in dramatically less research examining ableism in the industry itself compared to other instances of minority discrimination. Such a consistent disregard for disability begs the question: are disabled people seen exclusively as players rather than contributors to the next generation of the games industry?

Critical disability studies coined the social model of disability, which affirms that individuals are disabled by a societal context as well as an individual’s physical or mental condition (Hahn 1985). As a result, disability can be a created “social product” (Fougeyrollas et al. 2019). Disabling situations are thus the specific societal contexts in which disability is reinforced (Hamonet & Gracies 2013). If 25% of professional GDs disclose a disabled identity (IGDA 2019) and are regularly exposed to extreme and demanding working conditions, there is then substantial risk for disabling situations to occur within game development.

The games industry is infamous for relying on periods of compulsory overtime, otherwise known as crunch (Cote & Harris 2020). GDs who crunch operate under significant duress and may experience psychosomatic health issues and degraded work satisfaction (Niemelä 2021). Disabled GDs are especially vulnerable to such effects due to disabling situations resulting from a potentially decreased capacity for working overtime (Walls & Batiste 1996) or manifestations of external and internalized ableism, such as forced disclosure of disability (Charmaz 2010). Nevertheless, the number of GDs reporting recent use of crunch has nearly doubled in just two years (IGDA 2021). Crunch has been a continuously popular topic of study in gaming circles throughout the 2000s (Dyer-Witheford & de Peuter 2006); unsurprisingly however, the disabled GD experience is explored significantly less – both in regards to crunch, and in the industry as a whole.

Game company values are reflected in the practical realities of development (Flanagan 2009), including recruitment. While interpersonal interactions in work environments can be discriminatory, disabled people also experience ableism from inaccessible systems related to human resources (Reber et al. 2022). As we continue to survive a global pandemic and mass disabling event, inaccessible recruitment practices will prevent exponentially more talent from succeeding in the games industry.

Inaccessible recruitment practices can be characterized as microaggressive (Keller & Galgay 2010) and operate under key assumptions that a candidate adheres to the following traits: a candidate is obviously able-bodied (Baert 2016; Scholz 2020), and would disclose being disabled (Ameri et al. 2017); a candidate is or will be perceived by coworkers as productive (Østerud 2022; McLaughlin et al. 2004); and a candidate is not or will not be perceived by coworkers as a distinct or separate category of worker (Kwon & Archer 2022; Mik-Meyer 2016). It is likewise assumed by employers that they are or would be more compelled to hire a disabled candidate than other employers (Andersson et al. 2015). And even if a game company were to avoid these key assumptions, recruitment practices may still fail to account for invisible disabilities (Kattari et al. 2018; Syma 2019), such as cognitive disabilities and chronic illness.

The means by which GD careers are established and maintained are core to improving practical realities in game development. Just as consumer-focused disciplines iterate in the pursuit of a final shippable product (e.g. the design discipline of games user experience), recruitment practices should follow a similar pattern of iteration in such a dynamic labor market. Yet, the norms of secrecy and limited information flow have led to little being publicly available to prospective developers regarding the accessibility of game development (Kulik et al. 2021).

Related industry norms, including resistance to work-from-home accommodations or forced return-to-office policies, as well as the aforementioned crunch, are no longer strictly topics of research and discussion; instead, norms are being challenged by a burgeoning labor rights movement. The first successful pushes for unionization amongst GDs are emblems of unprecedented momentum (Weststar & Legault 2019). Now more than ever, the accessibility of game development is of collective industry interest (Cote & Harris 2020; Das et al. 2021) and disabled perspectives are salient.

A Disabled Perspective

As an autistic, chronically ill student GD with ADHD, I began this research out of frustration. After years of emails containing “impressed” or “unfortunately,” and rejections that always came despite seemingly positive rounds of interviews, I was eager to improve as a developer. I wanted to learn everything I could from contributing to live projects, but I eventually discovered there is a limit to what we can do on our own. I became concerned: was my potential as a disabled candidate being artificially limited in a competitive and demanding job market?

An overall lack of industry support for disabled prospective GDs like myself made breaking into the games industry seem impossible. Common pieces of advice that I observed in game development spheres pertained to either: networking through massively inaccessible in-person industry meet-ups in an ongoing pandemic; or an underlying assumption that disabled candidates must have the same energy levels and time available as our non-disabled counterparts to dedicate toward job applications.

I noticed impressive and successful diversity efforts being directed to many underemployed communities, meanwhile disabled people were practically left to fend for ourselves. It became evident that diversity includes disability, but game companies might not. I spent hours meeting with every professional who was willing to offer feedback or advice. And I realized I could examine the current landscape to hopefully encourage others like me that they are not alone in their quest to enter an unaccommodating, rigorous industry.

As a first step toward emphasizing the disabled GD experience, the following pilot study was designed to illustrate the level of consideration for disabled candidates exhibited by game companies – including those which comparatively excel in considering other marginalized identities.

Research Design

This study proposed that disabled candidates were not being sufficiently equipped to successfully enter and succeed in the games industry. It was hypothesized that game company recruitment efforts operate under an incorrect assumption where recruitment is an inherently neutral or objective practice, rather than a field subject to ableism in companies’ search for an ideal candidate. It was consequentially proposed that disabled people were being excluded from talent recruitment (Hoque & Bacon 2021). It was further hypothesized that game companies specifically addressing disability, rather than general diversity, was uncommon. Disabled GDs were ethnographically centered through an inductive thematic analysis of 20 AAA game companies’ public facing documentation to determine if disabled people are functionally excluded from being talent recruitment.

The game companies selected were the first AAA studios the disabled GD and researcher applied to as a student seeking entry-level employment. Data was collected in the form of compiling screenshots and excerpts from game company websites. This study qualified a game company website as a career hub or page. Some companies had singular all-purpose websites, which qualified for this study by default. The order in which data was collected was directly informed by each website’s layout, as the intent was that a member of the websites’ intended audience would follow the perceived user experience flow.

Consider Nintendo of America’s website as an example. Nintendo’s landing page features quick navigation to site content at the top, but also directs users to the following pages by scrolling down the landing page itself. Data was thus collected from Nintendo of America in the following order: “Benefits & Perks” (Image 1.1), “Life at Nintendo” (Image 1.2), “Diversity, Equity & Inclusion” (Image 1.3), and finally “About Us” (Image 1.4).

Image 1.1 – Nintendo of America “Benefits & Perks”

Image 1.2 – Nintendo of America “Life at Nintendo”

Image 1.3 – Nintendo of America “Diversity, Equity & Inclusion”

Image 1.4 – Nintendo of America “About Us”

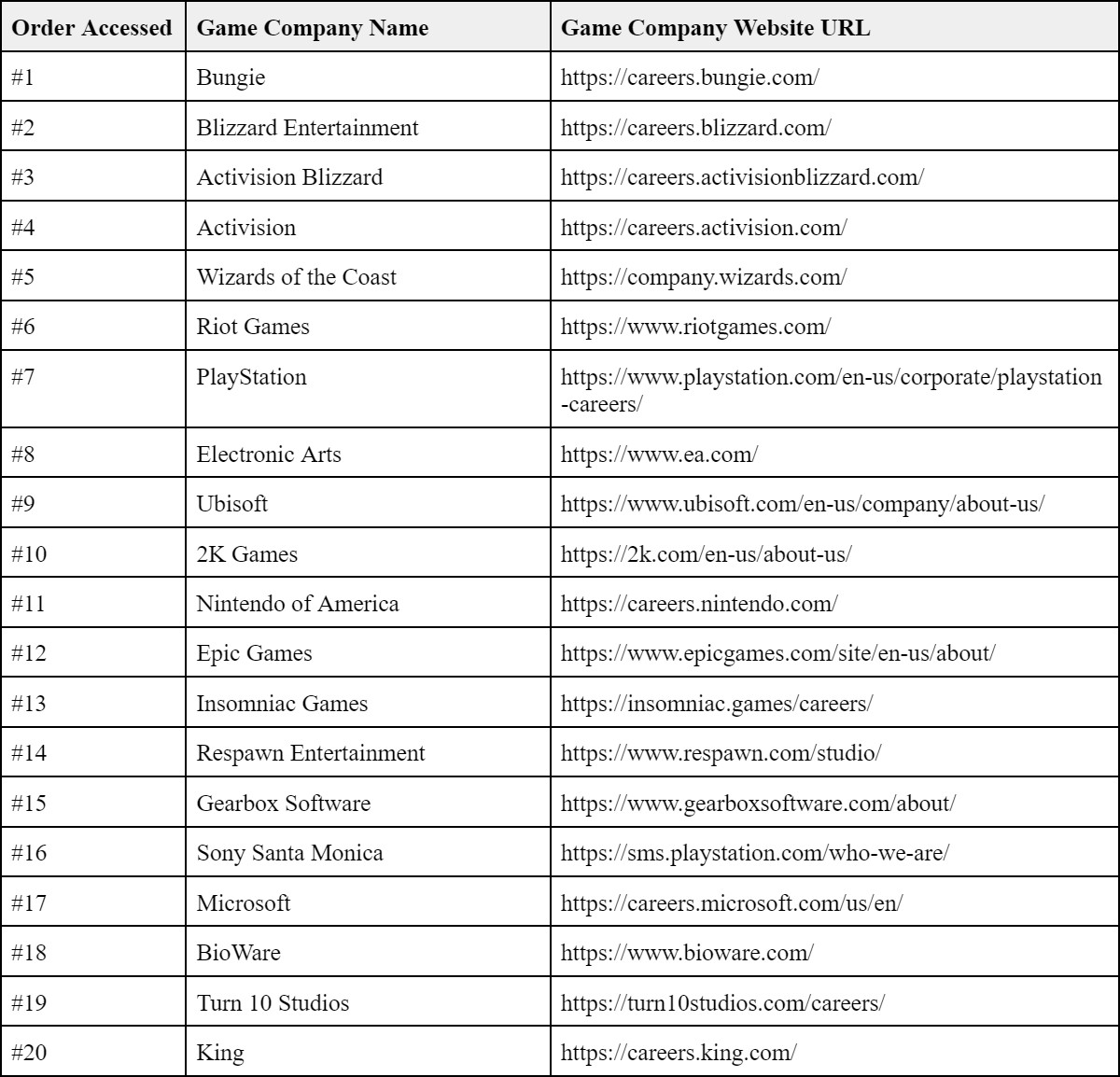

The 20 AAA game company websites were accessed for data collection from November 2022 to December 2022 in the following randomized order (Figure 1).

Figure 1. AAA Game companies examined and website URLs

Data was organized under five classifications: Taglines, identified by mission or vision statements (Image 2.1).

Image 2.1. Blizzard Entertainment, example tagline

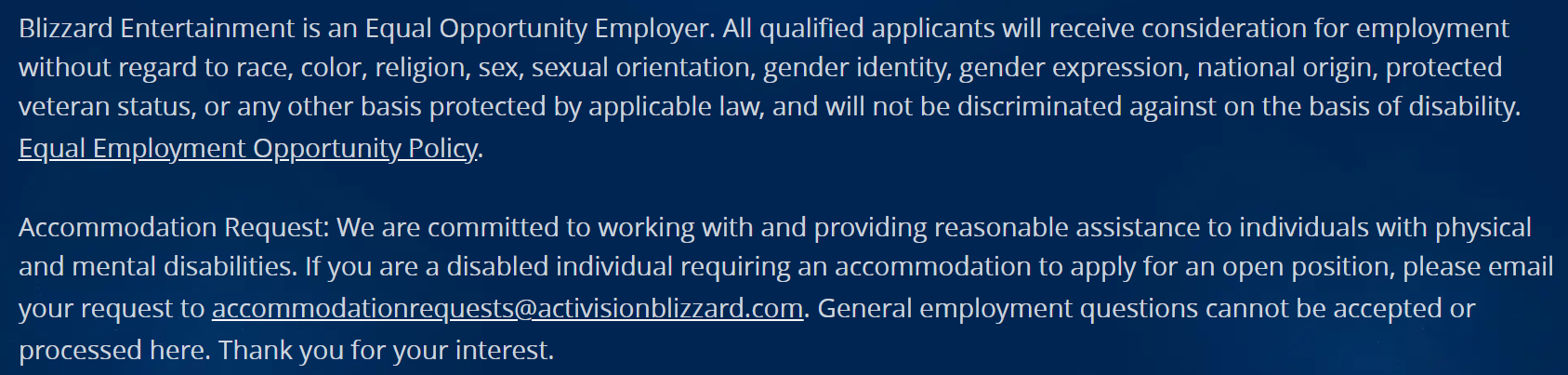

Equal opportunity disclosures, identified by legal employment notices (Image 2.2).

Image 2.2. Activision Blizzard, example equal opportunity disclosure

Core values, identified by “we” action statements, such as “we value” or “we hold” (Image 2.3).

Insert Image 2.3. King, example core values

Culture statements, identified as internally focused taglines which emphasize recruitment, including information on locale, etc. (Image 2.4).

Insert Image 2.4. Electronic Arts, example culture statements

And closers, identified as information placed immediately before or nearby website elements which redirect users to job listings (Image 2.5).

Insert Image 2.5. Epic Games, example closer

Results

Through thematic document analysis, there were four prevailing themes throughout the 20 game companies examined. Theme 1 was Recruiter Info, which gauged if the game company website directed candidates to recruiter information, such as a point of contact email, recruitment-focused Twitter, or LinkedIn (Image 3). Theme 1 was primarily present in culture statements and closers. 55% of game companies directed users to recruiter information (Figure 2).

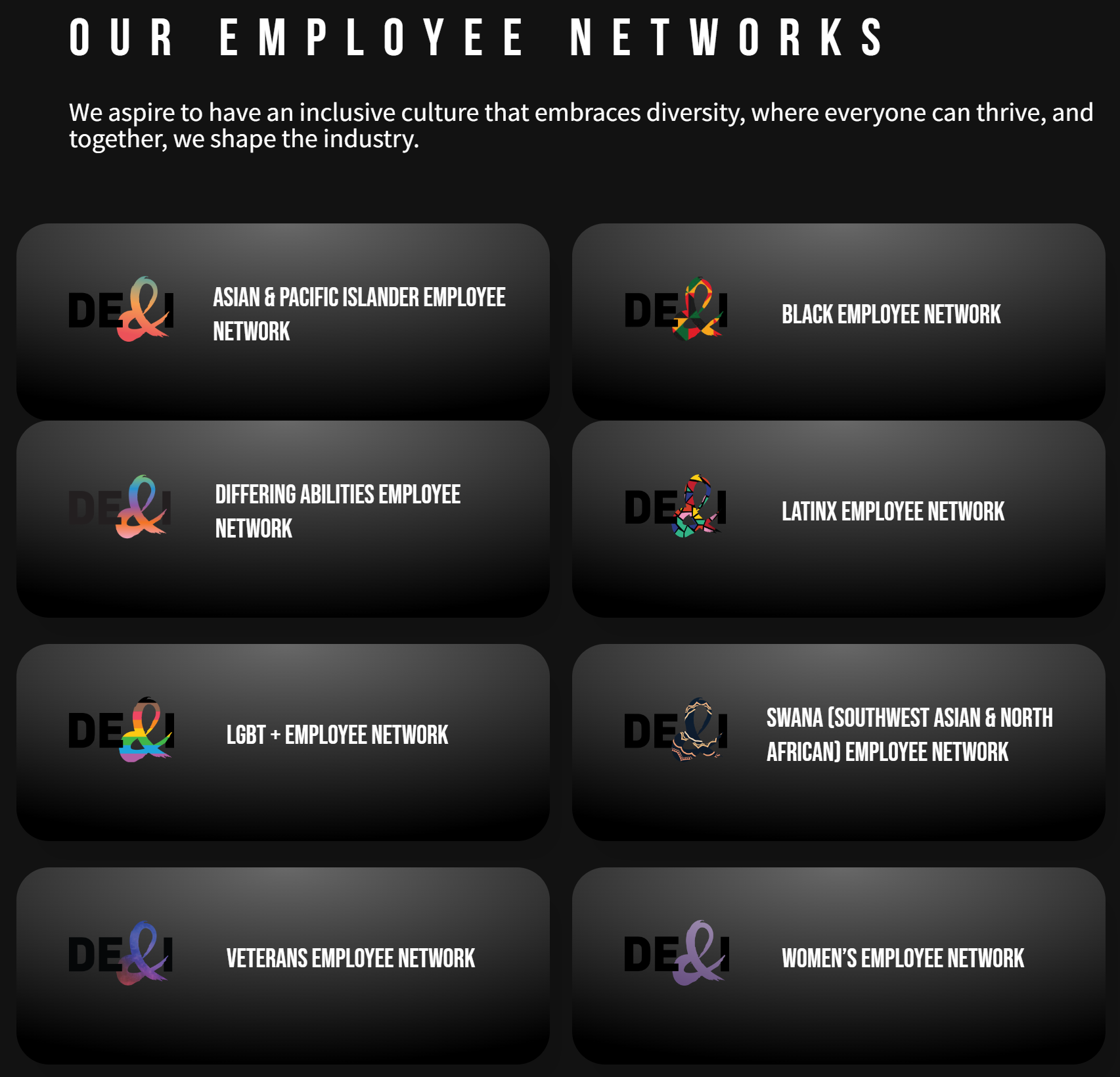

Image 3. Activision, example of Theme 1 present

Theme 2 was DEI Values (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion), which gauged if company culture statements specified DEI-oriented values (Image 4). DEI-oriented was defined as something directed toward conventional benefactors of diversity, equity, and inclusion practices – including historically marginalized communities (e.g. Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, queer, trans, gender-nonconforming, disabled, neurodiverse, etc.). Theme 2 was primarily present in taglines, equal opportunity disclosures, and core values. 60% of game companies specified DEI-oriented values (Figure 2).

Image 4. Bungie, example of Theme 2 present

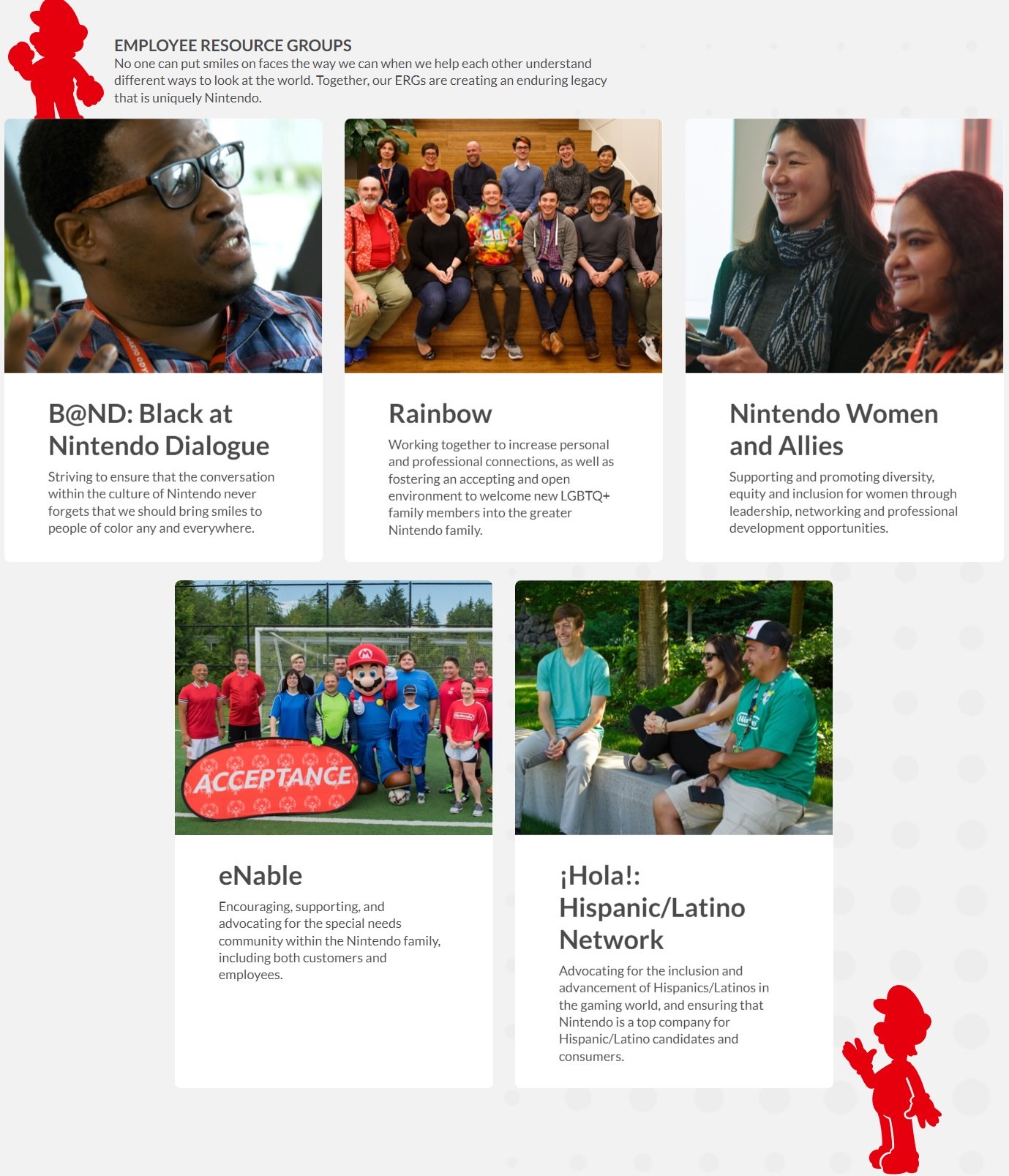

Theme 3 was DEI Examples, which gauged if game companies provided examples of DEI-oriented values in practice (Image 5). Examples included employee resource groups (ERG) and company DEI reports. Theme 3 was primarily present in core values and culture statements. If Theme 2 was present for a game company website, Theme 3 was also present. If Theme 2 was not present, Theme 3 and Theme 4 were also not present. The same 60% of game companies which specified DEI-oriented values also provided examples of DEI-oriented values in practice (Figure 2).

Image 5. PlayStation, example of Theme 3 present

Theme 4 was Disability Specified, which gauged if disability is included in provided examples of DEI-oriented values in practice (Image 6). Theme 4 was present in culture statements, mainly in the form of ERGs. 35% of game companies specifically referenced disability (Figure 2). Only 10% of game companies had all four themes present, and only 10% had no themes present.

Image 6. Activision Blizzard, example of Theme 4 present

Discussion

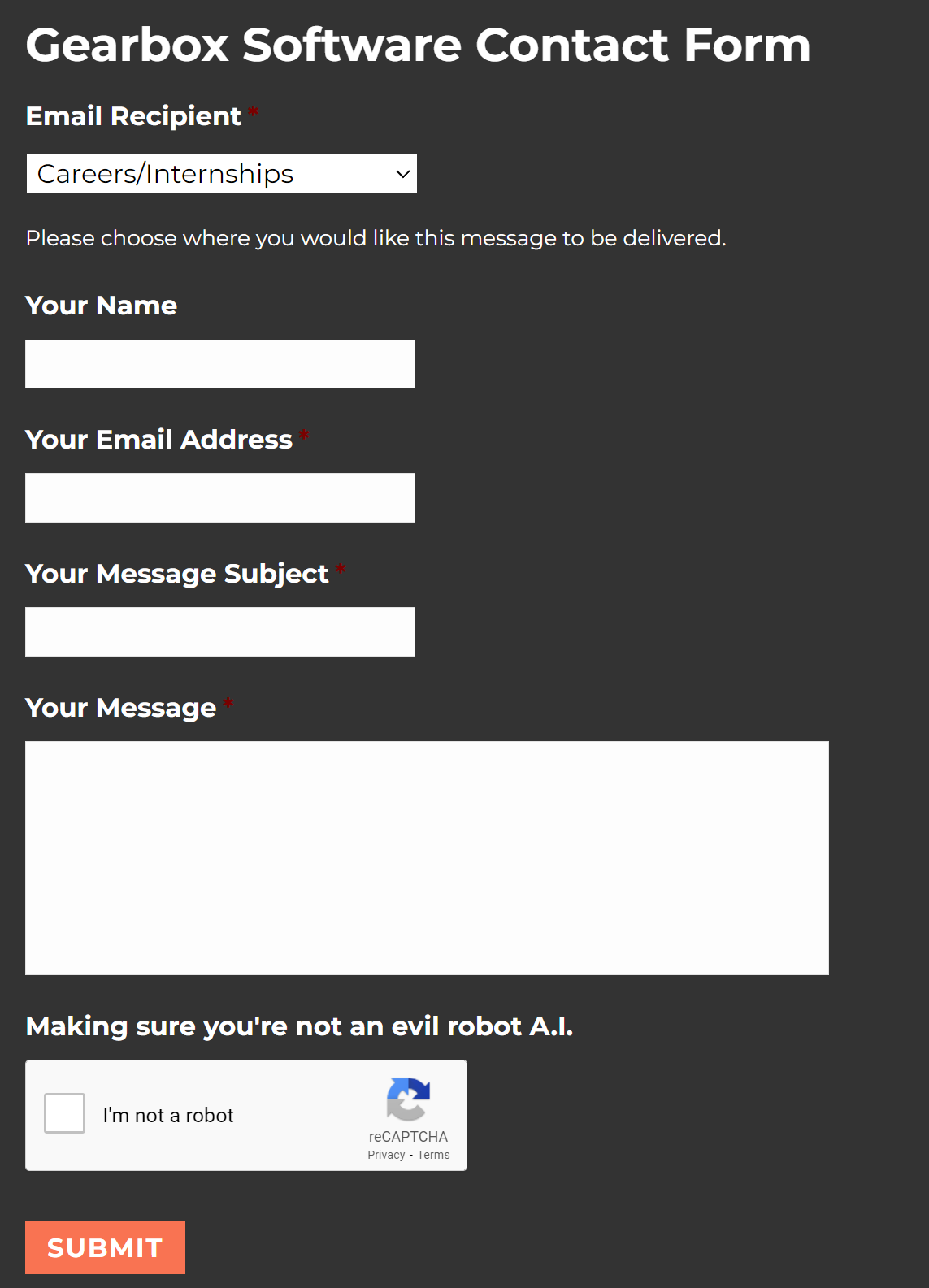

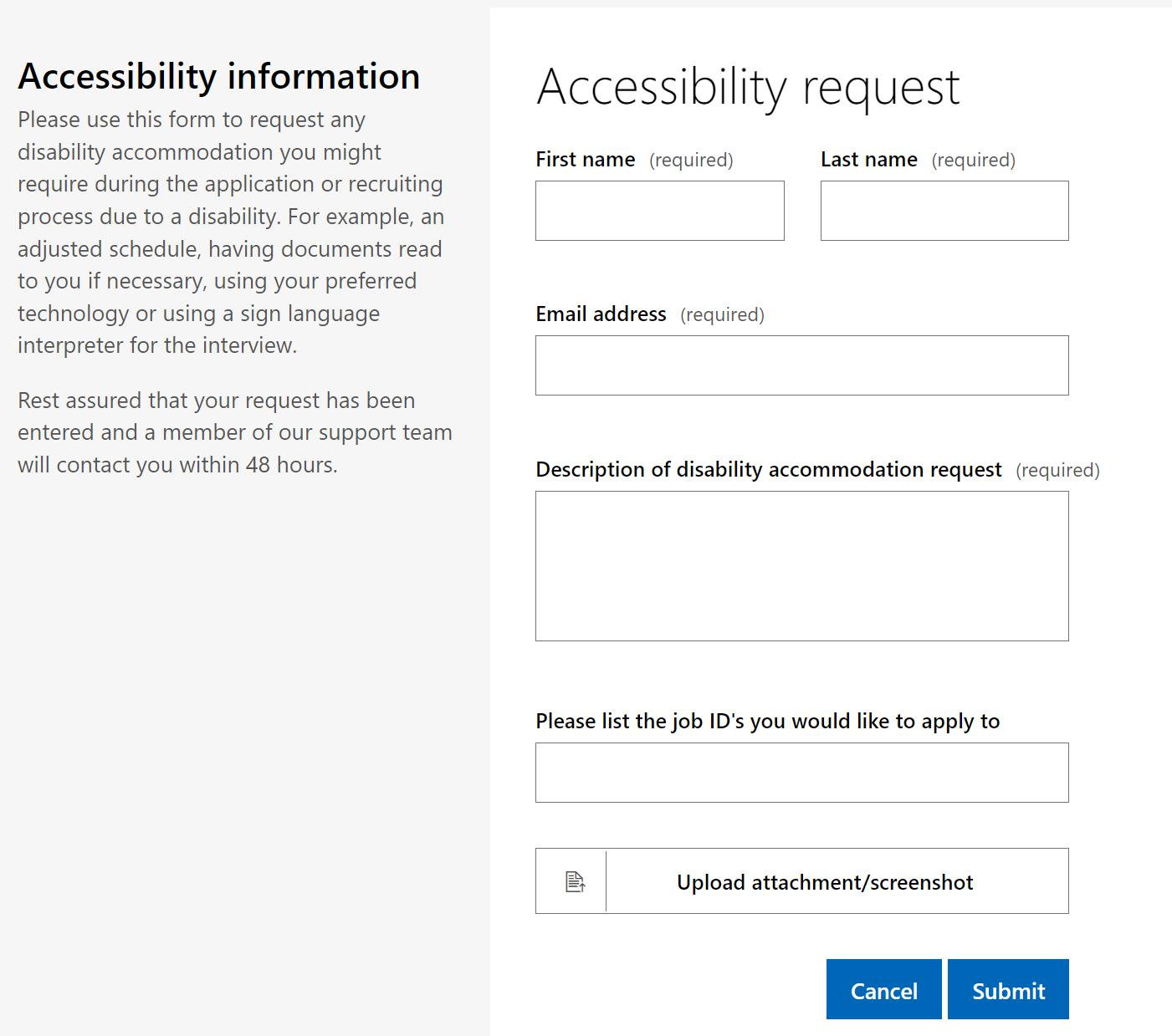

A follow-up analysis of the above themes’ prevalence is revealing. Companies such as Gearbox Software, Microsoft, and Blizzard Entertainment exceeded expectations for Theme 1 by providing multiple avenues to contact specific departments, including dedicated recruitment accessibility request forms from Microsoft and Blizzard.

Image 7.1. Gearbox Software, “Gearbox Software Contact Form”

Image 7.2. Microsoft, “Accessibility request

Image 7.3. Blizzard, “Accommodation Request”

The majority of game companies where Theme 1 was present were dependent upon LinkedIn rather than more open channels of communication. By excluding LinkedIn, the original rate of 55% dropped to 30%. Further, the five game companies where only Theme 1 was present were all exclusively dependent upon LinkedIn, and would have otherwise had no themes present: Epic Games, Sony Santa Monica, BioWare, and Turn 10 Studios. Insomniac Games demonstrated an impressive degree of transparency regarding the company recruiting process (Image 8.1) and excelled with Theme 1 by providing a dedicated contact form for Insomniac HR (Image 8.2), but failed to satisfy Theme 2 by not specifying any DEI-oriented values.

Image 8.1. Insomniac Games, recruiting process transparency

Image 8.2. Insomniac Games, “Contact Insomniac HR”

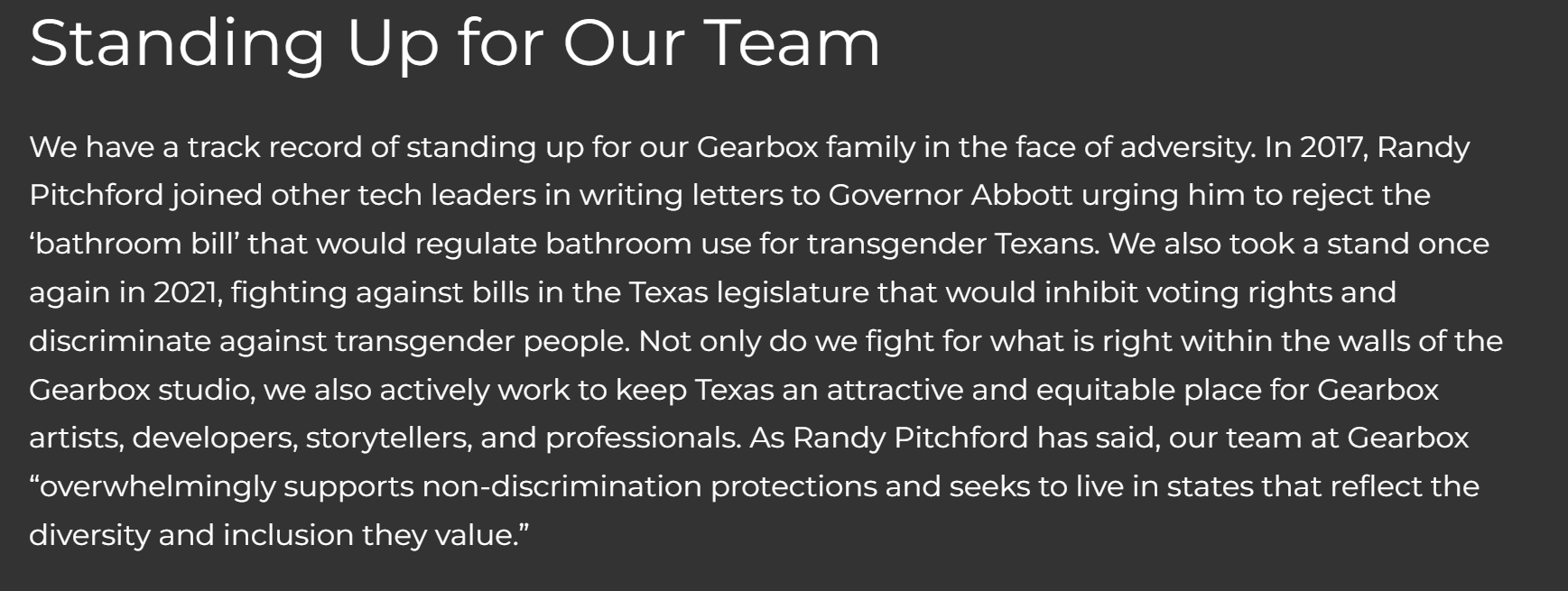

However, said degree of transparency could be arguably more impactful than the typical diversity-speak (Kulik et al. 2021). This may demonstrate a partial flaw in this thematic structure and may motivate further research on DEI-oriented values in practice (i.e. Theme 3). Gearbox Software likewise provided significant transparency for the recruiting process (Image 9.1), but exceeded Insomniac by specifying DEI-oriented values. Gearbox Software also satisfied Theme 3 by referencing a history of fighting institutional transphobia (Image 9.2).

Image 9.1. Gearbox Software, recruiting process transparency

Image 9.2. Gearbox Software, “Standing Up for Our Team”

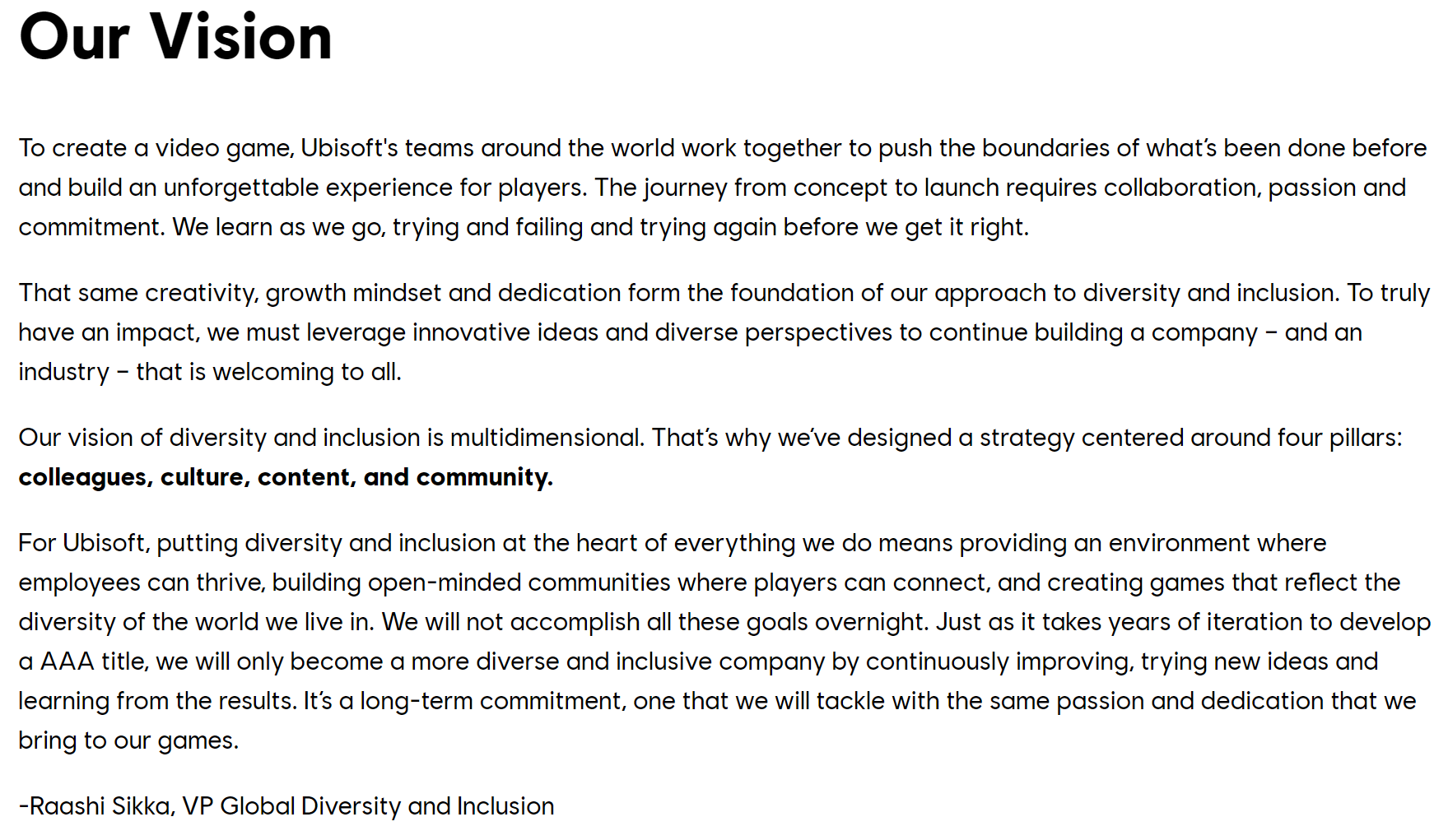

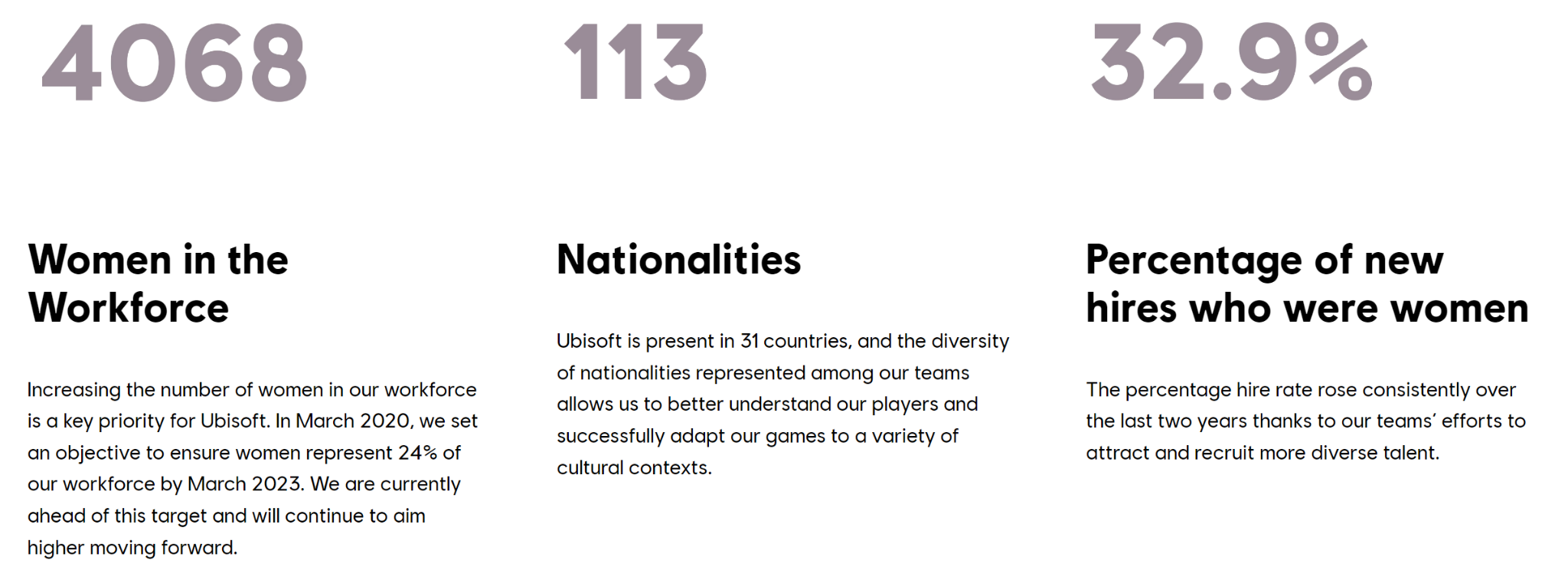

As for game companies where no themes were present, one of the two total stood out despite not adhering to the thematic structure. This paper perceived Respawn Entertainment as a company actively seeking talent – but there were only arguable claims of diversity with zero stated applications. Contrasted with its counterpart, 2K Games, Respawn Entertainment was perceived as more welcoming to prospective talent due to the game company website referencing said prospective talent. 2K Games, however, made no reference to developers whatsoever and was thus not perceived as a studio actively seeking talent at all – especially not disabled talent. Meanwhile, culture statements for companies such as Ubisoft expressed sentiments which satisfied Theme 2 and aligned with this paper’s perspective on recruitment in the games industry: “Just as it takes years of iteration to develop a AAA title, we will only become a more diverse and inclusive company by continuously improving, trying new ideas and learning from the results” (Image 10.1). This statement was demonstrated in Ubisoft’s transparent workforce representation statistics (Image 10.2), which satisfied Theme 3.

Image 10.1. Ubisoft, “Our Vision”

Image 10.2. Ubisoft, workforce representation statistics

There were five game companies where Theme 4 was present exclusively due to disability or neurodiversity ERGs: Bungie, Wizards of the Coast, Electronic Arts, Ubisoft, and Nintendo of America. However, the language used to describe Nintendo of America’s disability ERG raised alarming red flags, including even the ERG name: “eNable ERG. Encouraging, supporting, and advocating for the special needs community within the Nintendo family” (Image 11). The phrase “special needs” has been widely deprecated by the disabled community as an “ineffective euphemism” (Gernsbacher et al. 2016), and this paper therefore assumed minimal disabled involvement in Nintendo of America DEI initiatives.

Image 11. Nintendo of America, “eNable ERG”

As predicted, game companies acknowledging disabled GDs at all was significantly uncommon. The two game companies where only Theme 4 was not present were Gearbox Software and King – both of which performed well overall, but nonetheless failed to specifically address disability. Epic Games offered a comprehensive guide to company internships, and outright stated: “We wish to enable success for emerging talent by demystifying the critical talent pipelines and skills our teams look for and provide realistic pathways into Epic” (Image 12). And yet, Epic Games provided no evidence this mentality informed active recruitment strategies whatsoever.

Image 12. Epic Games, “When You Succeed, We Succeed”

Theme 3 was instead present for Riot Games, and DEI-oriented values were consistent for a variety of marginalized identities and corresponding ERGs (Image 13).

Image 13. Riot Games, ERGs

Electronic Arts also satisfied Theme 3, and stood out by highlighting pay equity (Image 14.1) and user accessibility (Image 14.2). Even still, Riot, Epic, and Electronic Arts were all alike in seeming to forget disabled developers altogether.

Image 14.1. Electronic Arts, “Our Commitment to Pay Equity”

Image 14.2. Electronic Arts, “Accessibility Portal”

The only three game companies that provided recruiter info, specified and provided examples of DEI-oriented values, and included disability in those examples, were: Activision, Ubisoft, and Microsoft. And even among these, disability was spottily considered. The description of Ubisoft’s Neurodiversity ERG was noticeably less people-focused than other Ubisoft ERGs (Image 15).

Image 15. Ubisoft, ERGs

Black Employees at Ubisoft was described as “to champion the advancement of Black employees.” UbiProud, a queer ERG, was described as “members want to… help each other excel at the workplace and provide the opportunities to do so.” Then, the Neurodiversity ERG stated, “its focus is on… ensuring video games foster belonging for all.” Activision’s Differing Employee Network ERG also emphasized disabled users over disabled GDs (Image 16). Nintendo of America’s aforementioned ERG exhibited a similar discrepancy between a disability ERG and other ERGs (Image 11).

Image 16. Activision, “Accessibility in Our Games”

Microsoft seemed to stand alone as the most comprehensive and accessible game company website. Where Insomniac surpassed typical diversity-speak, Microsoft surpassed Insomniac due to consistent and constant multimodal communication to candidates (Image 17.1). Inclusive design was specified as a primary informant of company values (Image 17.2), and its application was apparent in the game company website itself.

Image 17.1. Microsoft, “Inclusive interviewing”

Image 17.2. Microsoft, “Inclusive thinking drives our innovation”

Even still, Microsoft provided extensive examples: “Microsoft is dedicated to infusing diversity and inclusion principles into our hiring, our communication, our innovation” (Image 17.3).

Image 17.3. Microsoft, “We’re taking action”

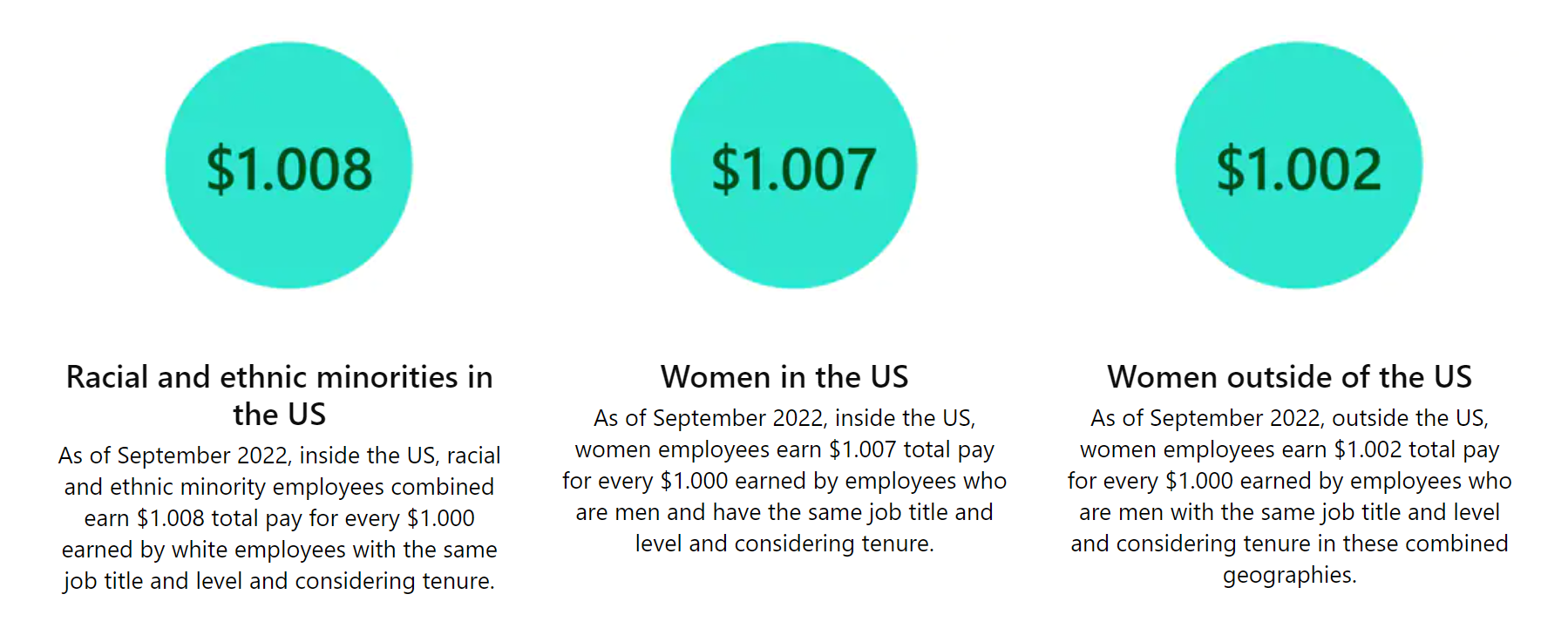

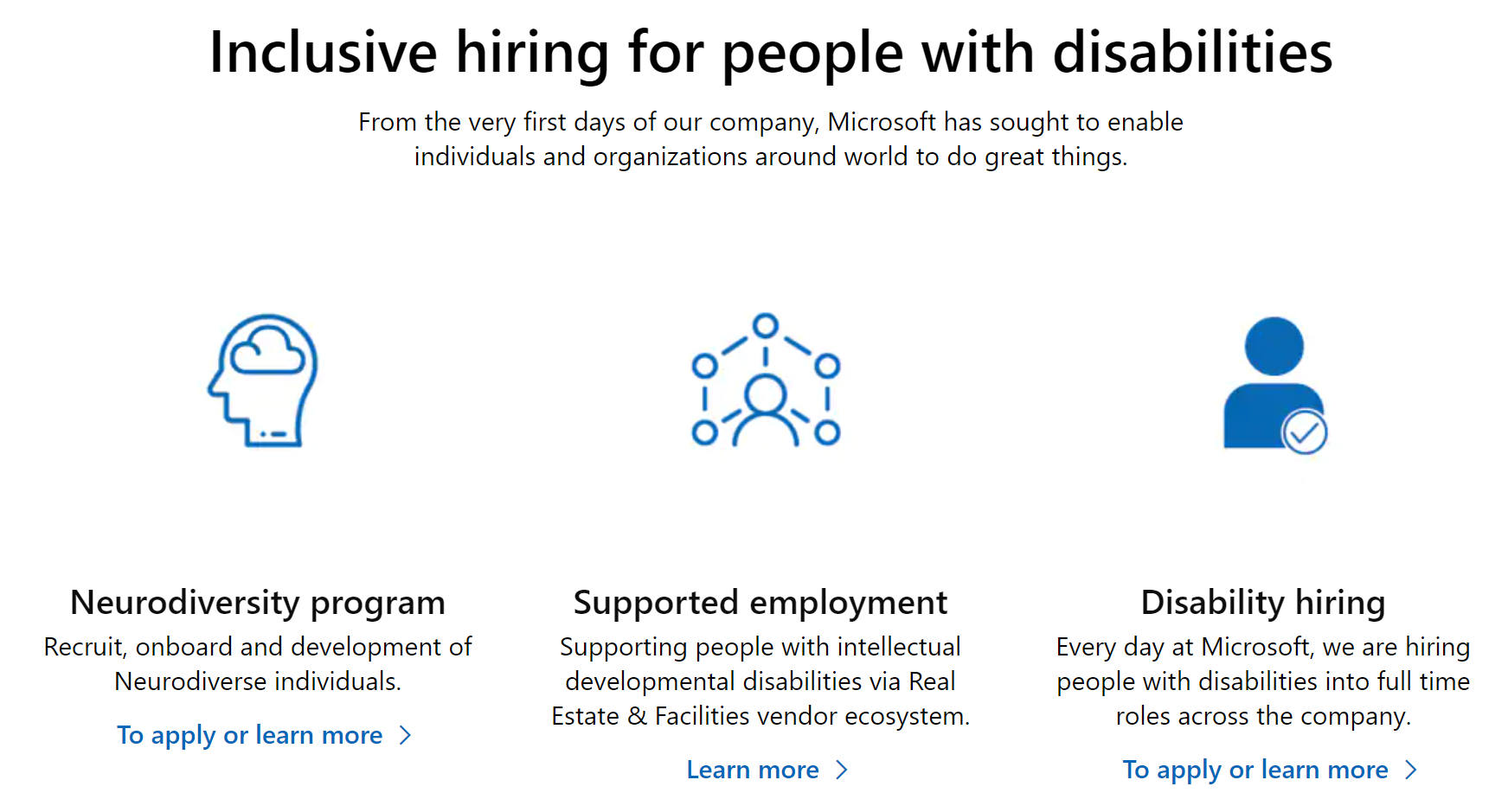

Between transparency regarding workforce diversity (Image 17.4), pay equity (Image 17.5), diversity and inclusion training (Image 17.6), and inclusive hiring programs (Image 17.7) – Microsoft seemed to almost pass with flying colors. So, why did these exciting findings still feel unsatisfying?

Image 17.4. Microsoft, workforce representation statistics

Image 17.5. Microsoft, pay equity

Image 17.6. Microsoft, diversity and inclusion training

Image 17.7. Microsoft, inclusive hiring programs

Conclusion

Where other marginalized identities are frequently accounted for, disabled GDs are widely disregarded. At best, internal retention resources like ERGs, or inclusive hiring programs, are available. At worst, game companies seem to perceive disabled people only as players. Microsoft was a beacon of hope as one of the final game companies examined in this study. Soon after, however, I was annoyed to be impressed by the sole game company that even approached the bare minimum for digital access. My initial excitement for Microsoft’s success diminished quickly when I found no evidence to suggest inclusive hiring programs are anything more than alternative job streams contingent upon self-disclosure of disability, and are potentially more vulnerable to prejudice compared to a unified job stream with inclusive policies meant to assist universal applicants.

Furthermore, ERGs and other internal retention resources only support current employees. By locking the vast majority of demonstrably limited assistance for disabled developers behind closed doors, game companies reveal their bias and support this paper’s hypothesis that games recruitment is incorrectly assumed to be a neutral or objective practice. How could game companies consider disabled people as candidates for the next generation of the games industry when they seemingly fail to support or acknowledge the 25% of disabled developers populating studios today (IGDA 2019)?

Notably, a growing number of game companies continue to rescind early COVID era work-from-home accommodations. It is this paper’s stance that such policy shifts are predicated in ableism. That said, it is worth distinguishing that office-oriented policies are not evil and work-from-home policies are not unilaterally good; disability, and by extension accessibility, is not a monolith. Rather, forced return-to-office policies are ableist because they restrict developer agency to a disabling degree. As a consequence, more and more game companies will outright disqualify disabled developers from honing their craft as future talent recruitment – and simultaneously endanger the health and livelihoods of disabled talent in the industry today.

Despite disabled candidates nonetheless seeking entry into professional game development, there are few reasons to suspect disability is accommodated or even allowed in AAA contexts. This paper recommends that game companies with inclusive values and companies desiring disabled prospective talent provide more explicit examples of ongoing EDI initiatives in public facing documentation.

Further research may better illuminate the impacts of inclusive hiring programs on disabled candidates in the games industry. Further research is also needed to identify industry norms negatively affecting recruitment and retention of disabled GDs.

Acknowledgement

This work was guided by my mentors Dr. Ashley Guajardo and Dr. Fernando Rodríguez. This work was supported by UROP from the Office of Undergraduate Research at the University of Utah awarded to Will Loxley.

References

Ameri, M., Schur, L., Adya, M., Bentley, F. S., McKay, P., & Kruse, D. (2018). The Disability Employment Puzzle: A Field Experiment on Employer Hiring Behavior. ILR Review, 71(2), 329–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793917717474

Andersson, J., Luthra, R., Hurtig, P., et al. (2015). Employer attitudes toward hiring persons with disabilities: a vignette study in Sweden. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 43(1), 41–50. Retrieved from https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-vocational-rehabilitation/jvr753.

Baert, S. (2016). Wage subsidies and hiring chances for the disabled: some casual evidence. Eur J Health Econ, 17, 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0656-7

Charmaz, K. (2010), “Disclosing illness and disability in the workplace”, Journal of International Education in Business, Vol. 3 No. 1/2, pp. 6-19. https://doi.org/10.1108/18363261011106858

Cote, Harris, B. C. (2021). The cruel optimism of “good crunch”: How game industry discourses perpetuate unsustainable labor practices. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211014213

Cote, & Harris, B. C. (2020). ‘Weekends became something other people did’: Understanding and intervening in the habitus of video game crunch. Convergence (London, England), 27(1), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856520913865

Das, M., Tang, J., Ringland, K., Piper, A. M. (2021). Toward Accessible Remote Work: Understanding Work-from-Home Practices of Neurodivergent Professionals. Association for Computing Machinery, 5(183), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449282

Dyer-Witheford, N., de Peuter, G. (2006). “EA Spouse” and the Crisis of Video Game Labour: Enjoyment, Exclusion, Exploitation, Exodus. Canadian Journal of Communication, 31(3), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2006v31n3a1771

Flanagan, M. (2009). Critical Play : Radical Game Design. MIT Press. Retrieved from https://utah-primoprod.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/dtufc4/UUU_ALMA51422 706070002001.

Fougeyrollas, P., Boucher, N., Edwards, G., Grenier, Y. and Noreau, L., 2019. The Disability Creation Process Model: A Comprehensive Explanation of Disabling Situations as a Guide to Developing Policy and Service Programs. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 21(1), pp.25–37. http://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.62

Gernsbacher, M. A., Raimond, A. R., Balinghasay, M. T., & Boston, J. S. (2016). “Special needs” is an ineffective euphemism. Cognitive research: principles and implications, 1(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-016-0025-4

Hahn, H. (1985). Toward a Politics of Disability: Definitions, Disciplines, and Policies. University of Southern California. Retrieved from www.independentliving.org/docs4/hahn2.html.

Hamonet, C., Gracies, J.-M. (2013). Disabling situations, an original concept connecting disease, disability, and rehabilitation to assess and manage disabled persons. 7th World Congress of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. Retrieved from http://claude.hamonet.free.fr/eng/art_disability-situations.htm

Hoque, K., Bacon, N. (2021). Working from home and disabled people’s employment outcomes. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 60(1), 1–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12645

Kattari, S. K., Olzman, M., & Hanna, M. D. (2018). “You Look Fine!”: Ableist Experiences by People With Invisible Disabilities. Affilia, 33(4), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109918778073

Keller, R. M., & Galgay, C. E. (2010). Microaggressive experiences of people with disabilities. In: D. W. Sue (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact, 241–267. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Kulik, J., Beeston, J., Cairns, P. (2021). Grounded Theory of Accessible Game Development. Association for Computing Machinery, 28, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1145/3472538.3472567

Kwon, C., Archer, M. (2022). Conceptualizing the Marginalization Experiences of People with Disabilities in Organizations Using an Ableism Lens. Human Resource Development Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/15344843221106561

McLaughlin, M. E., Bell, M. P., Stringer, D. Y. (2004). Stigma and Acceptance of Persons With Disabilities: Understudied Aspects of Workforce Diversity.

Mik-Meyer, N. (2016). Othering, ableism and disability: A discursive analysis of co-workers’ construction of colleagues with visible impairments. Human Relations, 69(6), 1341–1363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715618454

Niemelä, J. (2021). A Systematic Mapping Study of Crunch Time in Video Game Development. University of Oulu. Retrieved from https://oatd.org/oatd/record?record=oai\:oulu.fi\:nbnfioulu-202106178507.

O’Donnell. (2014). Developer’s Dilemma : the secret world of videogame creators. Retrieved from https://utah-primoprod.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/dtufc4/UUU_ALMA51559 730820002001.

Reber, L., Kreschmer, J. M., James, T. G., Junior, J. D., DeShong, G. L., Parker, S., & Meade, M. A. (2022). Ableism and Contours of the Attitudinal Environment as Identified by Adults with Long-Term Physical Disabilities: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7469. MDPI AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127469

Revillard, A. (2022). Disabled People Working in the Disability Sector: Occupational Segregation or Personal Fulfillment? Work, Employment and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170221080401

Scholz, F. (2020). Taken for Granted: Ableist Norms Embedded in the Design of Online Recruitment Practices. In: Fielden, S.L., Moore, M.E., Bend, G.L. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Disability at Work. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-42966-9_26

Syma, C. (2019), “Invisible disabilities: perceptions and barriers to reasonable accommodations in the workplace”, Library Management, Vol. 40 No. 1/2, 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-10-2017-0101

Taylor, T. L. (2006). Play Between Worlds: Exploring Online Game Culture. Habitat LucasArts Inc, MIT Press.

Walls, R.T., Batiste, L.C. (1996). Job Accommodations for Fatigue in the Workplace. Technology and Disability, Vol. 5 No. 3–4, 334–343.

Weststar & Legault, M.-J. (2019). Building Momentum for Collectivity in the Digital Game Community, Television & New Media, 20(8), 848–861. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1527476419851087

Weststar, J., Kumar, S., Coppins, T., Kwan, E., Inceefe, E. (2021). Developer Satisfaction Survey 2021. International Game Developers Association. Retrieved from https://igda-website.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/18113901 /IGDA-DSS-2021_SummaryReport_2021.pdf.

Weststar, J., Kwan, E., Kumar, S. (2019). Developer Satisfaction Survey 2019. International Game Developers Association. Retrieved from https://s3-us-east-2.amazonaws.com/igda-website/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/29093706 /IGDA-DSS-2019_Summary-Report_Nov-20-2019.pdf.

Weststar, & Legault, M.-J. (2017). Why Might a Videogame Developer Join a Union? Labor Studies Journal, 42(4), 295–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160449X17731878

Østerud, K. L. (2022). Disability Discrimination: Employer Considerations of Disabled Jobseekers in Light of the Ideal Worker. Work, Employment and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211041303