Social and Behavioral Science

133 Associations Among Maternal Trauma History, Prenatal Emotion Dysregulation, and Prenatal Sleep Quality

Marissa Larkin

Faculty Mentor: Sheila Crowell (Psychology, University of Utah)

ABSTRACT

Sleep is an increasingly recognized correlate and predictor of long-term mental and physical health. Those who have endured traumas throughout their lifespan may experience mental and physical health difficulties, including poor sleep quality. One group of individuals who are especially vulnerable to experiencing poor sleep quality are pregnant women, especially those who have experienced trauma. The overarching aim of this study was to examine how maternal trauma history may be related to sleep quality during pregnancy. We also examined if the relation between maternal trauma history and sleep quality varied across levels of emotion dysregulation, given our hypothesis that emotion regulation skills may buffer the effects of trauma on sleep quality. Eighty-six 3rd-trimester pregnant women aged 19-38 completed self- report measures pertaining to traumatic life experiences, emotion dysregulation, and subjective sleep quality. Hierarchical linear regression models revealed that higher levels of emotion dysregulation predicted poorer sleep quality during pregnancy. Maternal trauma history did not predict prenatal sleep quality, nor did this relation vary across levels of emotion dysregulation. Given that poor prenatal sleep has been associated with negative maternal postnatal health outcomes, offspring development, and maternal-infant relationships, our study highlights the utility of improving emotion regulation skills during pregnancy as a means for also improving sleep quality. The current study is one of few to examine emotion dysregulation during pregnancy and provides additional evidence that it may be an important factor for identifying mental health concerns during pregnancy.

Keywords: emotion dysregulation, pregnancy, sleep quality, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Adequate sleep is critical for mental and physical health across the lifespan (Alvarez & Ayas, 2004; Clement-Carbonell et al., 2021; Medic et al., 2017). Consequences of poor sleep can include diabetes, heart attack, depression, and anxiety (Clement-Carbonell et al., 2021; Colten & Altevogt, 2006; Medic et al., 2017). One group of individuals who are especially vulnerable to experiencing poor sleep are those who are pregnant (Facco et al., 2010; Hedman et al., 2002; Kennedy et al., 2007; Mindell & Jacobson, 2000; Mindell et al., 2015; Sedov et al., 2018).

Numerous biological and anatomical changes during pregnancy confer risk for poor sleep (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2012; Hedman et al., 2002; Kennedy et al., 2007; Kizilirmak et al., 2012; Mindell et al., 2015; Sedov et al., 2018); however, not all pregnant people experience the same severity of sleep disturbances. Why do some pregnant people experience especially poor sleep quality?

Poor prenatal sleep has been associated with various aspects of maternal postnatal health, including higher risk of postpartum depression (Chang et al., 2010; Okun et al., 2009; Pietikäinen et al., 2018), gestational diabetes (Facco et al., 2017), and greater and longer lasting weight gain (Sharkey et al., 2016). Poor prenatal sleep quality has also been linked to effects on offspring development, such as a higher risk of preterm birth (Micheli et al., 2011), low birth weight (Plancoulaine et al., 2017), difficulties with sleep throughout childhood (Armstrong et al., 1998), delay of gross motor and language development (Li et al., 2023), poor executive function (Lahti-Pulkkinen et al., 2018), and a general increased risk of psychiatric problems and poor neurodevelopment (Lahti-Pulkkinen et al., 2018). As for maternal-infant relationships, poor prenatal sleep quality has been associated with a higher risk of infant negative reactivity (Ciciolla et al., 2022), maternal and infant sleep problems (Ciciolla et al., 2022), difficulty with breastfeeding (Gordon et al., 2021), maternal fatigue (Pires et al., 2010), postpartum depression

(Chang et al., 2010; Okun et al., 2009; Pietikäinen et al., 2018; Pires et al., 2010), and insecure mother-child attachment security (Newland et al., 2016). Given that poor prenatal sleep has been associated with these outcomes, it is important to identify risk and protective factors for prenatal sleep health. Clarifying these susceptibility factors will help to inform intervention efforts for pregnant people in greatest need of those supports.

Maternal Trauma History and Prenatal Sleep Quality

Sleep disturbances and symptoms indicative of clinical sleep disorders increase significantly across the duration of pregnancy (Facco et al., 2010; Hedman et al., 2002; Kennedy et al., 2007; Mindell & Jacobson, 2000; Mindell et al., 2015; Sedov et al., 2018). Subjective sleep quality, specifically, may be poor as early as the 1st trimester of pregnancy and worsens substantially by the 3rd trimester due to frequent urges to urinate, restless legs, physical discomfort, snoring, and ruminations about childbirth and parenting (Fernández-Alonso et al., 2012; Hedman et al., 2002; Kalmbach et al., 2020; Kennedy et al., 2007; Kizilirmak et al., 2012; Mindell et al., 2015; Sedov et al., 2018). In addition to these physical factors affecting sleep quality, research has indicated that women’s experiences with trauma across the lifespan influence prenatal sleep (Gelaye et al., 2015; Miller-Graff & Cheng, 2017; Nevarez-Brewster et al., 2022; Sanchez et al., 2016; Takelle et al., 2022). Both childhood abuse—particularly, physical and sexual abuse—and intimate partner violence during adulthood have been associated with poor sleep quality during pregnancy (Gelaye et al., 2015; Miller-Graff & Cheng, 2017; Nevarez-Brewster et al., 2022; Sanchez et al., 2016; Takelle et al., 2022). The association between maternal trauma history and prenatal sleep quality may be due to psychological factors, such as depression and ongoing trauma symptoms during adulthood (Gelaye et al., 2015). In addition, this association may be due to the fact that traumatic life experiences can alter the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which also is involved in the regulation of sleep (Buckley & Schatzberg, 2005; Heim et al., 2008). Specifically, chronic trauma exposure can increase HPA axis hyperactivity and cortisol production, which then can contribute to increased awakenings, sleep fragmentation, and decreased slow-wave sleep (Buckley & Schatzberg, 2005; Heim et al., 2008).

Emotion Dysregulation

Chronic and repeated trauma exposure also can have adverse effects on development that compromise emotion regulation abilities (Heleniak et al., 2015; Jenness et al., 2020; Kerig, 2018). Similar to how trauma may alter HPA axis activity, traumatic life experiences have been found to alter the limbic HPA axis, which facilitates emotion regulation (Kerig, 2018). Difficulties with emotion regulation, or emotion dysregulation, may be characterized by emotional experiences and expressions that are intense and interfere with interpersonal functioning and goal-directed behaviors (Crowell et al., 2020). Emotion dysregulation involves any combination of limited awareness, understanding, and acceptance of emotions; poor ability to control impulsive behaviors when upset; and limited capacity to regulate emotions in order to achieve one’s goals (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Emotion dysregulation as a result of childhood trauma has been associated with numerous psychopathologies and physical health risks, such as depression, anxiety, borderline personality disorder, cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, arthritis, and Alzheimer’s disease (Appleton et al., 2011; Ball et al., 2012; Crowell et al., 2015; Folk et al., 2014; Hofmann et al., 2012; Kerig, 2018; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002; Miranda et al., 2013). Among pregnant women, emotion dysregulation was found to be associated with depression, anxiety, borderline personality disorder, and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (Lin et al., 2019). Disturbed sleep is a key feature of many of these psychopathologies, and indeed, there is empirical evidence of associations between emotion dysregulation and poor sleep among non-pregnant adults (Ennis et al., 2017; Mauss et al., 2013; Palmer & Alfano, 2017). However, there is limited research on associations among trauma history, emotion dysregulation, and sleep quality among pregnant women, specifically.

The Current Study

To advance understanding of factors that influence sleep quality during pregnancy, we examined if maternal trauma history predicted prenatal sleep quality, and if the relation between maternal trauma history and prenatal sleep quality varied based on levels of emotion dysregulation. We hypothesized that more lifetime experiences with trauma would predict poorer prenatal sleep quality. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the relation between trauma history and sleep quality would not be the same across levels of emotion dysregulation. Specifically, we hypothesized that trauma history would predict poorer prenatal sleep quality among those who also reported high levels of emotion dysregulation, and the relation between trauma history and sleep quality would be nonsignificant among those who reported low levels of emotion dysregulation. This latter part of the hypothesis would suggest that effective emotion regulation abilities can buffer the effects of trauma on sleep quality.

METHOD

Participants

Participants (N = 86; Mage = 29.42, SD = 4.44 years) included 3rd-trimester pregnant women enrolled in a longitudinal study on sleep and emotion dysregulation during the perinatal period (R01MH119070, MPIs Crowell & Conradt; F31MH124275, PI Kaliush). Eligibility criteria included: (1) 18 to 40 years of age, (2) singleton pregnancy, (3) no present illicit substance use, and (4) no severe pregnancy complications (e.g., gestational diabetes, preeclampsia). All participants identified as women. The majority of participants identified as White (67.4%), and other racial identities included more than one race (9.3%), Asian (8.1%), Black or African American (4.7%), and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (1.2%). Some participants declined to report their race (5.8%), and others preferred to self-report their race (3.5%; e.g., Mexican, Middle Eastern). Approximately 25% of the sample identified as Hispanic or Latina, and 68.6% had been pregnant at least one other time before participating in the study. The sample was socioeconomically diverse, with the annual household income ranging from less than $5,000 (3.5%) to $250,000 or more (2.3%) and the most frequently reported income range being $75,000 to $99,999 (16.3%). The educational backgrounds of the sample include a high school degree or less (12.8%), some college but no degree (17.4%), technical school or associate’s degree (16.2%), bachelor’s degree (33.7%), or master’s or doctoral degree (19.8%; see Table 1 for additional demographics).

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board. The present study sample size (N = 86) aligned with that which was predetermined using regression-based power estimates. Participants were recruited and enrolled to achieve a uniform distribution on a measure of emotion dysregulation to yield a sample with a wide range of distress and emotion regulation difficulties. Researchers recruited pregnant women from various obstetrics and gynecology clinics within the University of Utah Healthcare system. Prior to recruitment, the women were screened via their online medical records to exclude those who already met specific exclusion criteria. Interested and eligible pregnant women were then contacted by study staff to coordinate participation during their 3rd trimester of pregnancy.

Participation included online questionnaires assessing demographics, psychopathology, and trauma history, as well as seven consecutive daily surveys assessing sleep health. All questionnaires were completed via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; https://www.project-redcap.org/) and Qualtrics (http://www.qualtrics.com), both of which are secure web applications. Participants were financially compensated with online gift cards.

Measures

Emotion Dysregulation. The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item self-report measure designed to assess various aspects of emotional dysregulation—namely, difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviors, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, nonacceptance of emotional responses, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Sample items include, “When I’m upset, I become out of control” and “When I’m upset, I believe I will stay that way for a long time”. Participants respond to these items with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Almost Never) to 5 (Almost Always). Total scores are summed and can range from 36 to 180; higher scores indicate greater difficulty with emotion regulation. In the present sample, the DERS total score demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .96).

Maternal Trauma History. The Traumatic Experiences of Betrayal across the Lifespan (TEBL; Kaliush et al., under review) assesses maternal trauma history. The TEBL examines numerous components of 22 distinct traumatic life experiences, including the accumulation, frequency, chronicity, and developmental timing of those potential traumas. Traumatic life experiences assessed by the TEBL are primarily interpersonal in nature and align with life experiences recognized as traumatic by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th edition (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2019) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The measure comprises yes-or-no questions, typically preceded by the prompt, “At any time in your life, has someone with whom you were close or trusted…,” followed by an item such as “… ignored you or withheld praise or affection to make you feel badly about yourself?” If participants endorsed a traumatic life experience, they were prompted to indicate approximately how many times they experienced that trauma during different developmental stages: infancy to early childhood (0-5), middle childhood (6-11), adolescence (12-17), adulthood (18+), age 18 to their current pregnancy, and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimesters of their current pregnancy. In the present study, maternal trauma history was represented by a score ranging from 0 to 22 reflecting the accumulation of trauma across the lifespan, or the number of distinct traumatic life experiences the participant endorsed.

Subjective Sleep Quality. The Consensus Sleep Diary (CSD; Carney et al., 2012) is a standardized self-monitoring tool that assesses numerous sleep health parameters, including sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, and subjective sleep quality. Over the course of seven consecutive mornings, participants answered questions pertaining to their previous night’s sleep, including ratings of their sleep quality ranging from 1 (Very poor) to 5 (Very good). Participants’ daily sleep quality ratings were averaged to obtain one score reflecting overall subjective sleep quality during their 3rd trimester of pregnancy.

Covariates. Participants’ age and parity were included as covariates. Age was included because of empirical evidence that sleep quality deteriorates with increasing age, especially among women (Madrid-Valero et al., 2017). Parity is commonly included as a covariate in perinatal research because it is theorized that women in their first pregnancy may experience stressors and psychopathology differently than do women who were previously pregnant one or more times (Narayan et al., 2018).

Analytic Plan

Preliminary Analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 27 (IBM Corp, 2020). Descriptive analyses were run to determine demographic information as well as the range of values for maternal trauma history, emotion dysregulation, and prenatal sleep quality. We also ran Pearson bivariate correlation analyses to examine associations among demographic variables, maternal trauma history, emotion dysregulation, and prenatal sleep quality. No data were missing. We grand-mean-centered the continuous predictor variables (i.e., maternal trauma history and emotion dysregulation) to account for potential multicollinearity when creating an interaction term. We ensured that the outcome variable, prenatal sleep quality, met assumptions of normality in order to run linear regression models.

Primary Analyses. We ran hierarchical linear regression models to test maternal trauma history and emotion dysregulation as predictors of prenatal sleep quality. In block 1 of the model, we included planned covariates (i.e., parity and age). In block 2, we included maternal trauma history and emotion dysregulation. Finally, in block 3, we included the interaction between maternal trauma history and emotion dysregulation. This analytic procedure revealed if the interaction between maternal trauma history and emotion dysregulation predicted prenatal sleep quality above and beyond the main effects and covariates.

RESULTS

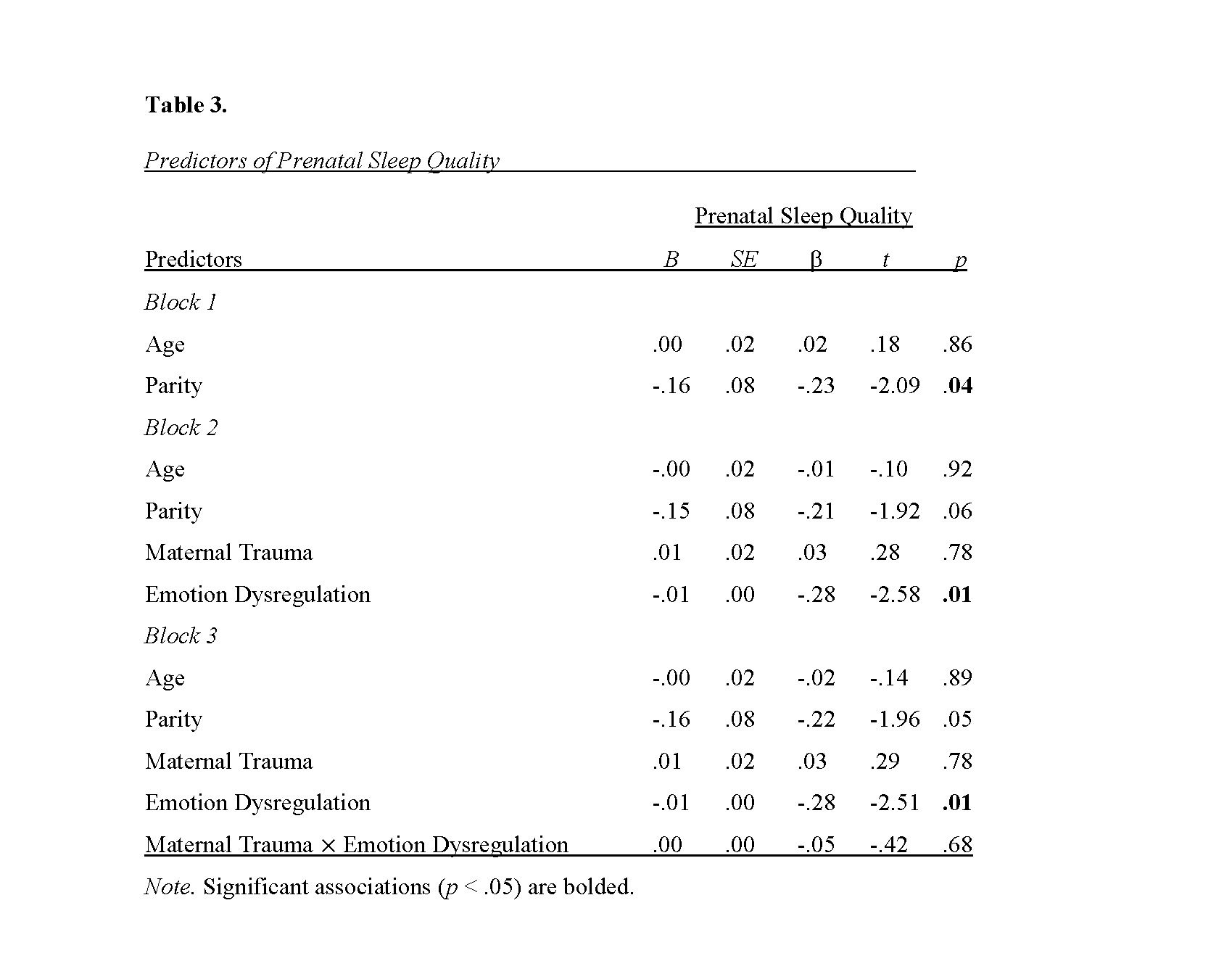

Bivariate Correlations (Table 2)

First, correlation analyses revealed a significant association between parity and prenatal sleep quality, r(84) = -.22, p = .04, such that a higher number of pregnancies across the lifespan was associated with poorer sleep quality during the current pregnancy. In addition, prenatal emotion dysregulation was significantly correlated with prenatal sleep quality, r(84) = -.28, p = .01, such that greater difficulties with regulating emotions were associated with poorer sleep quality.

Emotion dysregulation was also significantly correlated with maternal trauma history, r(84) =.30, p = .01. Specifically, more traumatic life experiences were associated with higher levels of prenatal emotion dysregulation. Finally, maternal trauma history was significantly correlated with parity, r(84) = .24, p = .03, such that women who reported more pregnancies over their lifespan also endorsed more traumatic life experiences.

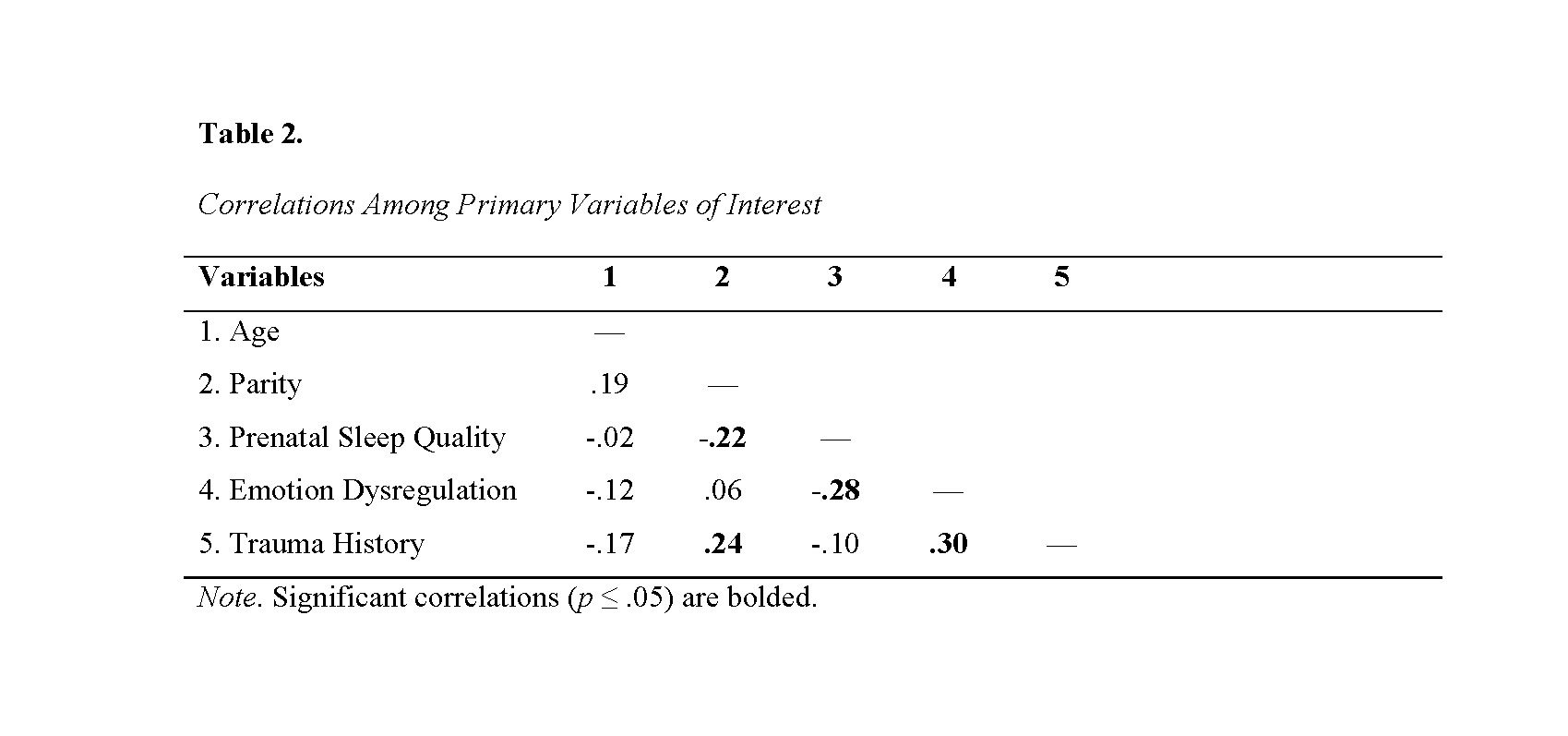

Hierarchical Linear Regression Models (Table3)

In block 1 of the model, results indicated that parity predicted prenatal sleep quality, B = –.16, β = -.23, p = .04. For each additional pregnancy in one’s life, prenatal sleep quality declined by .16 units. In block 2, emotion dysregulation and maternal trauma history were entered into the model, and the effect of parity on prenatal sleep quality became nonsignificant, B = -.15, β = –

.21, p = .06. Instead, maternal emotion dysregulation emerged as a significant predictor of prenatal sleep quality, B = -.01, β = -.28, p = .01. For every one unit increase in emotion dysregulation, prenatal sleep quality declined by .01 units. Maternal trauma history did not predict prenatal sleep quality, B = .01, β = .03, p = .78. Finally, in block 3, results indicated that there was not a significant interaction between emotion dysregulation and maternal trauma history on prenatal sleep quality, B = .00, β = -.05, p = .68. Overall, this regression model accounted for approximately 13% of the variance in prenatal sleep quality.

DISCUSSION

The overarching aim of this study was to examine how maternal trauma history may be related to sleep quality during pregnancy. We also examined if the relation between maternal trauma history and sleep quality may vary across levels of emotion dysregulation. Results indicated that higher levels of emotion dysregulation predicted poorer sleep quality during pregnancy. However, maternal trauma history did not predict prenatal sleep quality, and this relation did not vary across levels of emotion dysregulation.

Our finding that emotion dysregulation predicted poor prenatal sleep quality is consistent with previous research on psychopathology and sleep health. Pregnancy is a time of significant psychological, social, and neurobiological changes, which oftentimes are associated with stress and risk for psychopathology (Brummelte et al., 2010; Dhillon et al., 2017; Escott et al., 2004; Evans et al., 2001; Furtado et al., 2018; Grote et al., 2010; Heron et al., 2004; Huizink et al., 2004; Lutterodt et al., 2019; Penner & Rutherford, 2022; Rich-Edwards et al., 2006; Wallace & Araji, 2020). Pregnancy-related stressors can prompt emotional, cognitive, and physiological arousal, which reduces sleep quality (Fairholme & Manber, 2015; Vafapoor et al., 2018; Vandekerckhove & Wang, 2017). Similarly, difficulties with emotion regulation have been found to be associated with depression, borderline personality disorder, anxiety, and self- injurious thoughts and behaviors among pregnant women, and disturbed sleep is a common characteristic of these psychopathologies (Ennis et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2019; Palmer & Alfano, 2017).

Just as the prenatal period may be a time of heightened risk for psychopathology, it also is a time when intervention efforts can have lasting positive effects on maternal postnatal health (Braeken et al., 2016; Duncan & Bardacke, 2009; Dunn et al., 2012; Milgrom et al., 2011; Pat et al., 2019; Spinelli & Endicott, 2003), offspring development (Braeken et al., 2016; Glover, 2014; van den Heuvel et al., 2015), and maternal-infant relationships (de Campora et al., 2014; Duncan & Bardacke, 2009; Glover, 2014; Milgrom et al., 2011). There is a growing body of research demonstrating that mindfulness-based interventions, Dialectical Behavior Therapy-informed skills groups, and mentalization-based treatments can be adapted for pregnant populations and significantly improve emotion regulation skills (Lucena et al., 2020; Penner & Rutherford, 2022; Slade et al., 2019; Wilson & Donachie, 2018). Given our finding that emotion dysregulation predicted poor prenatal sleep quality, it may be that these emotion regulation interventions also could improve perinatal sleep health. Thus, we encourage researchers to include measures of sleep health, including subjective sleep quality, in their studies on perinatal emotion regulation interventions.

Our finding that maternal trauma history did not predict prenatal sleep quality was unexpected. Although previous studies have reported significant associations between maternal trauma history and sleep (Gelaye et al., 2015; Miller-Graff & Cheng, 2017; Nevarez-Brewster et al., 2022; Sanchez et al., 2016; Takelle et al., 2022), most studies did not include measures of emotion dysregulation. Our results indicated that maternal trauma history was associated with emotion dysregulation, and emotion dysregulation predicted poor sleep quality. It may be worthwhile to examine these relations over time to determine if emotion dysregulation is a mechanism through which maternal trauma history influences perinatal sleep quality. In addition, it may be worthwhile to distinguish between types of maternal trauma. Prior research has found that childhood threat experiences, such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and exposure to violence, were highly associated with emotion dysregulation and, in turn, mental health problems, but childhood deprivation experiences, such as physical and emotional neglect and separation from primary caregivers, were not associated with emotion dysregulation (Greene et al., 2021). It will be important for future research on maternal trauma history and perinatal sleep to adopt a more nuanced and theoretically-informed conceptualization of traumatic life experiences.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study had several strengths, including a novel participant recruitment strategy using a measure of emotion dysregulation, which yielded a sample with a wider range of emotional distress. Also, recruitment efforts were made to over-sample for historically minoritized racial and ethnic identities, which increased the diversity of the sample and generalizability of the results. However, there are limitations to address in future research. First, all of the measures were self-reported, which could be prone to social desirability and common- method biases. Second and relatedly, our measure of maternal trauma history was retrospective, which renders it susceptible to recall biases and limited agreement with prospective measures (Baldwin et al., 2019; Newbury et al., 2018; Talari & Goyal, 2020).

However, low agreement between retrospective and prospective measures of childhood maltreatment may not necessarily imply that retrospective measures have poor validity (Baldwin et al., 2019). Additional research has suggested that prospective measures may only account for the most severe childhood maltreatment cases and that retrospective childhood maltreatment measures are more strongly associated with subjective measures of physical and emotional health (Reuben et al., 2016). Thus, children prospectively identified as having experienced maltreatment may have different risk pathways than adults reporting childhood maltreatment retrospectively (Baldwin et al., 2019). Ultimately, researchers must be aware of these measurement differences and limitations, as they may capture different risk pathways based on their chosen method (Baldwin et al., 2019).

Conclusions and Future Directions

In sum, results from the current study indicate that emotion dysregulation may increase risk for poor sleep quality during pregnancy. Given that prenatal sleep has been associated with maternal postnatal health (Chang et al., 2010; Facco et al., 2017; Okun et al., 2009; Pietikäinen et al., 2018; Sharkey et al., 2016), offspring development (Armstrong et al., 1998; Lahti-Pulkkinen et al., 2018; Li et al., 2023; Micheli et al., 2011; Plancoulaine et al., 2017), and maternal-infant relationships (Chang et al., 2010; Ciciolla et al., 2022; Gordon et al., 2021; Newland et al., 2016; Okun et al., 2009; Pietikäinen et al., 2018; Pires et al., 2010), our study highlights the potential relevance of emotion regulation interventions during pregnancy for improving maternal sleep health. In addition to future studies measuring these constructs over time and distinguishing between types of maternal trauma history, researchers may consider examining bidirectional relations between emotion dysregulation and sleep quality because prior research has indicated that poor sleep quality also can increase emotion dysregulation (Kahn et al., 2013; Palmer & Alfano, 2017; Vandekerckhove & Wang, 2017; Walker & Helm, 2009). The current study is one of few to examine emotion dysregulation during pregnancy and provides additional evidence that it may be an important factor for identifying mental health concerns during pregnancy. Identifying risk and protective factors for prenatal health is essential to inform intervention efforts for pregnant people and their families.

REFERENCES

Alvarez, G. G., & Ayas, N. T. (2004). The impact of daily sleep duration on health: A review of the literature. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing, 19(2), 56–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0889-7204.2004.02422.x

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Appleton, A. A., Buka, S. L., McCormick, M. C., Koenen, K. C., Loucks, E. B., Gilman, S. E., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2011). Emotional functioning at age 7 years is associated with C- reactive protein in middle adulthood. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(4), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0b013e31821534f6

Armstrong, K. L., O’Donnell, H., McCallum, R., & Dadds, M. (1998). Childhood sleep problems: Association with prenatal factors and maternal distress/depression. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 34(3), 263–266. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440- 1754.1998.00214.x

Baldwin, J. R., Reuben, A., Newbury, J. B., & Danese, A. (2019). Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76, 584– 593. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0097

Ball, T. M., Ramsawh, H. J., Campbell-Sills, L., Paulus, M. P., & Stein, M. B. (2012). Prefrontal dysfunction during emotion regulation in generalized anxiety and panic disorders.

Psychological Medicine, 43(7), 1475–1486. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291712002383

Braeken, M. A. K. A., Jones, A., Otte, R. A., Nyklíček, I., & Van den Bergh, B. R. H. (2016). Potential benefits of mindfulness during pregnancy on maternal autonomic nervous system function and infant development. Psychophysiology, 54(2), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12782

Brummelte, S., & Galea, L. A. M. (2010). Depression during pregnancy and postpartum: Contribution of stress and ovarian hormones. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 34(5), 766–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.09.006

Buckley, T. M., & Schatzberg, A. F. (2005). On the interactions of the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal (HPA) axis and sleep: Normal HPA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplary sleep disorders. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(5), 3106–3114. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1056

Carney, C. E., Buysse, D. J., Ancoli-Israel, S., Edinger, J. D., Krystal, A. D., Lichstein, K. L., & Morin, C. M. (2012). The consensus sleep diary: Standardizing prospective sleep self- monitoring. Sleep, 35(2), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1642

Chang, J. J., Pien, G. W., Duntley, S. P., & Macones, G. A. (2010). Sleep deprivation during pregnancy and maternal and fetal outcomes: Is there a relationship? Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.001

Ciciolla, L., Addante, S., Quigley, A., Erato, G., & Fields, K. (2022). Infant sleep and negative reactivity: The role of maternal adversity and perinatal sleep. Infant Behavior and Development, 66, 101664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2021.101664

Clement-Carbonell, V., Portilla-Tamarit, I., Rubio-Aparicio, M., & Madrid-Valero, J. J. (2021). Sleep quality, mental and physical health: A differential relationship. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020460

Colten, H. R., & Altevogt, B. M. (2006). Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation an unmet public health problem. Institute of Medicine.

Crowell, S. E., Puzia, M. E., & Yaptangco, M. (2015). The ontogeny of chronic distress: Emotion dysregulation across the life span and its implications for psychological and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.023

de Campora, G., Giromini, L., Larciprete, G., Li Volsi, V., & Zavattini, G. C. (2014). The impact of maternal overweight and emotion regulation on early eating behaviors. Eating Behaviors, 15(3), 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.04.013

Dhillon, A., Sparkes, E., & Duarte, R. V. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1421–1437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0726-x

Duncan, L. G., & Bardacke, N. (2009). Mindfulness-based childbirth and parenting education: Promoting family mindfulness during the perinatal period. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9313-7

Dunn, C., Hanieh, E., Roberts, R., & Powrie, R. (2012). Mindful pregnancy and childbirth: Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on women’s psychological distress and well- being in the perinatal period. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 15(2), 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0264-4

Ennis, C. R., Short, N. A., Moltisanti, A. J., Smith, C. E., Joiner, T. E., & Taylor, J. (2017). Nightmares and nonsuicidal self-injury: The mediating role of emotional dysregulation. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 76, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.04.003

Escott, D., Spiby, H., Slade, P., & Fraser, R. B. (2004). The range of coping strategies women use to manage pain and anxiety prior to and during first experience of labour. Midwifery, 20(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2003.11.001

Evans, J., Heron, J., Francomb, H., Oke, S., & Golding, J. (2001). Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ, 323(7307), 257–260. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257

Facco, F. L., Grobman, W. A., Reid, K. J., Parker, C. B., Hunter, S. M., Silver, R. M., Basner, R. C., Saade, G. R., Pien, G. W., Manchanda, S., Louis, J. M., Nhan-Chang, C.-L., Chung, J. H., Wing, D. A., Simhan, H. N., Haas, D. M., Iams, J., Parry, S., & Zee, P. C. (2017). Objectively measured short sleep duration and later sleep midpoint in pregnancy are associated with a higher risk of gestational diabetes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.066

Facco, F. L., Kramer, J., Ho, K. H., Zee, P. C., & Grobman, W. A. (2010). Sleep disturbances in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 115(1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e3181c4f8ec

Fairholme, C. P., & Manber, R. (2015). Sleep, emotions, and emotion regulation. Sleep and Affect, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-417188-6.00003-7

Fernández-Alonso, A. M., Trabalón-Pastor, M., Chedraui, P., & Pérez-López, F. R. (2012). Factors related to insomnia and sleepiness in the late third trimester of pregnancy. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 286(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404- 012-2248-z

Folk, J. B., Zeman, J. L., Poon, J. A., & Dallaire, D. H. (2014). A longitudinal examination of emotion regulation: Pathways to anxiety and depressive symptoms in urban minority youth. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 19(4), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12058

Furtado, M., Chow, C. H. T., Owais, S., Frey, B. N., & Van Lieshout, R. J. (2018). Risk factors of new onset anxiety and anxiety exacerbation in the perinatal period: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 238, 626–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.073

Gelaye, B., Kajeepeta, S., Zhong, Q.-Y., Borba, C. P. C., Rondon, M. B., Sánchez, S. E., Henderson, D. C., & Williams, M. A. (2015). Childhood abuse is associated with stress- related sleep disturbance and poor sleep quality in pregnancy. Sleep Medicine, 16(10), 1274–1280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.07.004

Glover, V. (2014). Maternal depression, anxiety and stress during pregnancy and child outcome; what needs to be done. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.017

Gordon, L. K., Mason, K. A., Mepham, E., & Sharkey, K. M. (2021). A mixed methods study of perinatal sleep and breastfeeding outcomes in women at risk for postpartum depression. Sleep Health, 7(3), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2021.01.004

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94

Greene, C. A., McCoach, D. B., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., & Grasso, D. J. (2021). Associations among childhood threat and deprivation experiences, emotion dysregulation, and mental health in pregnant women. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(4), 446–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001013

Grote, N. K., Bridge, J. A., Gavin, A. R., Melville, J. L., Iyengar, S., & Katon, W. J. (2010). A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(10), 1012. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111

Hedman, C., Pohjasvaara, T., Tolonen, U., Suhonen-Malm, A. S., & Myllylä, V. V. (2002). Effects of pregnancy on mothers’ sleep. Sleep Medicine, 3(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00130-7

Heim, C., Newport, D. J., Mletzko, T., Miller, A. H., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2008). The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(6), 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008

Heleniak, C., Jenness, J. L., Vander Stoep, A., McCauley, E., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2015). Childhood maltreatment exposure and disruptions in emotion regulation: A transdiagnostic pathway to adolescent internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(3), 394–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-015- 9735-z

Heron, J., O’Connor, T. G., Evans, J., Golding, J., & Glover, V. (2004). The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 80(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.004

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Fang, A., & Asnaani, A. (2012). Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 29(5), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21888

Huizink, A. C., Mulder, E. J. H., Robles de Medina, P. G., Visser, G. H. A., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2004). Is pregnancy anxiety a distinctive syndrome? Early Human Development, 79(2), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.04.014

IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp.

Jenness, J. L., Peverill, M., Miller, A. B., Heleniak, C., Robertson, M. M., Sambrook, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2020). Alterations in neural circuits underlying emotion regulation following child maltreatment: A mechanism underlying trauma- related psychopathology. Psychological Medicine, 51(11), 1880–1889. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720000641

Kahn, M., Sheppes, G., & Sadeh, A. (2013). Sleep and emotions: Bidirectional links and underlying mechanisms. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89(2), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.05.010

Kaliush, P. R., Kerig, P. K., Raby, K. L., Maylott, S. E., Neff, D., Speck, B., Molina, N. C., Pappal, A. E., Parameswaran, U. D., Conradt, E., & Crowell, S. E. (under review). Examining implications of the developmental timing of maternal trauma for prenatal and newborn outcomes.

Kalmbach, D. A., Cheng, P., Ong, J. C., Ciesla, J. A., Kingsberg, S. A., Sangha, R., Swanson, L. M., O’Brien, L. M., Roth, T., & Drake, C. L. (2020). Depression and suicidal ideation in pregnancy: Exploring relationships with insomnia, short sleep, and nocturnal rumination. Sleep Medicine, 65, 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2019.07.010

Kennedy, H. P., Gardiner, A., Gay, C., & Lee, K. A. (2007). Negotiating sleep. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 21(2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jpn.0000270628.51122.1d

Kerig, P.K. (2018). Emotion dysregulation and childhood trauma. In T.P. Beauchaine & S.E. Crowell (Eds.), The oxford handbook of emotion dysregulation (pp. 264–282). Oxford Library of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190689285.013.19

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., McGuire, L., Robles, T. F., & Glaser, R. (2002). Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: New perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135217

Kizilirmak, A., Timur, S., & Kartal, B. (2012). Insomnia in pregnancy and factors related to insomnia. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/197093

Lahti-Pulkkinen, M., Mina, T. H., Riha, R. L., Räikkönen, K., Pesonen, A. K., Drake, A. J., Denison, F. C., & Reynolds, R. M. (2018). Maternal antenatal daytime sleepiness and child neuropsychiatric and neurocognitive development. Psychological Medicine, 49(12), 2081–2090. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329171800291x

Li, Y.-S., Lee, H.-C., Huang, J.-P., Lin, Y.-Z., Au, H.-K., Lo, Y.-C., Chien, L.-C., Chao, H.-J.,Estinfort, W., & Chen, Y.-H. (2023). Adverse effects of inadequate sleep duration patterns during pregnancy on toddlers suspected developmental delay: A longitudinal study. Sleep Medicine, 105, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2023.02.022

Lin, B., Kaliush, P. R., Conradt, E., Terrell, S., Neff, D., Allen, A. K., Smid, M. C., Monk, C., & Crowell, S. E. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation: Part I. psychopathology, self-injury, and parasympathetic responsivity among pregnant women. Development and Psychopathology, 31(3), 817–831. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579419000336

Lucena, L., Frange, C., Pinto, A. C., Andersen, M. L., Tufik, S., & Hachul, H. (2020). Mindfulness interventions during pregnancy: A narrative review. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 18(6), 470–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2020.07.007

Lutterodt, M. C., Kähler, P., Kragstrup, J., Nicolaisdottir, D. R., Siersma, V., & Ertmann, R. K. (2019). Examining to what extent pregnancy-related physical symptoms worry women in the first trimester of pregnancy: A cross-sectional study in general practice. BJGP Open, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen19x101674

Madrid-Valero, J. J., Martínez-Selva, J. M., Ribeiro do Couto, B., Sánchez-Romera, J. F., & Ordoñana, J. R. (2017). Age and gender effects on the prevalence of poor sleep quality in the adult population. Gaceta Sanitaria, 31(1), 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.05.013

Mauss, I. B., Troy, A. S., & LeBourgeois, M. K. (2013). Poorer sleep quality is associated with lower emotion-regulation ability in a laboratory paradigm. Cognition & Emotion, 27(3), 567–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.727783

Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.2147/nss.s134864

Micheli, K., Komninos, I., Bagkeris, E., Roumeliotaki, T., Koutis, A., Kogevinas, M., & Chatzi, L. (2011). Sleep patterns in late pregnancy and risk of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction. Epidemiology, 22(5), 738–744. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0b013e31822546fd

Milgrom, J., Schembri, C., Ericksen, J., Ross, J., & Gemmill, A. W. (2011). Towards parenthood: An antenatal intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and parenting difficulties. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(3), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.045

Miller-Graff, L. E., & Cheng, P. (2017). Consequences of violence across the lifespan: Mental health and sleep quality in pregnant women. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(5), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000252

Mindell, J. A., & Jacobson, B. J. (2000). Sleep disturbances during pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 29(6), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2000.tb02072.x

Mindell, J. A., Cook, R. A., & Nikolovski, J. (2015). Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances across pregnancy. Sleep Medicine, 16(4), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.006

Miranda, R., Tsypes, A., Gallagher, M., & Rajappa, K. (2013). Rumination and hopelessness as mediators of the relation between perceived emotion dysregulation and suicidal ideation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(4), 786–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013- 9524-5

Narayan, A. J., Rivera, L. M., Bernstein, R. E., Harris, W. W., & Lieberman, A. F. (2018). Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: A pilot study of the benevolent childhood experiences (bces) scale. Child Abuse & Neglect, 78, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.022

Nevarez-Brewster, M., Aran, Ö., Narayan, A. J., Harrall, K. K., Brown, S. M., Hankin, B. L., & Davis, E. P. (2022). Adverse and benevolent childhood experiences predict prenatal sleep quality. Adversity and Resilience Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-022-00070

Newland, R. P., Parade, S. H., Dickstein, S., & Seifer, R. (2016). Goodness of fit between prenatal maternal sleep and infant sleep: Associations with maternal depression and attachment security. Infant Behavior and Development, 44, 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.06.010

Okun, M. L., Hanusa, B. H., Hall, M., & Wisner, K. L. (2009). Sleep complaints in late pregnancy and the recurrence of postpartum depression. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 7(2), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402000902762394

Palmer, C. A., & Alfano, C. A. (2017). Sleep and emotion regulation: An organizing, integrative review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 31, 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.12.006

Pan, W.-L., Chang, C.-W., Chen, S.-M., & Gau, M.-L. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based programs on mental health during pregnancy and early motherhood – a randomized control trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2503-4

Penner, F., & Rutherford, H. J. (2022). Emotion regulation during pregnancy: A call to action for increased research, screening, and intervention. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 25(2), 527–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-022-01204-0

Pietikäinen, J. T., Polo-Kantola, P., Pölkki, P., Saarenpää-Heikkilä, O., Paunio, T., & Paavonen, E. J. (2018). Sleeping problems during pregnancy—a risk factor for postnatal depressiveness. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 22(3), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0903-5

Pires, G. N., Andersen, M. L., Giovenardi, M., & Tufik, S. (2010). Sleep impairment during pregnancy: Possible implications on mother–infant relationship. Medical Hypotheses, 75(6), 578–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2010.07.036

Plancoulaine, S., Flori, S., Bat-Pitault, F., Patural, H., Lin, J.-S., & Franco, P. (2017). Sleep trajectories among pregnant women and the impact on outcomes: A population-based cohort study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(5), 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2212-9

Qualtrics. https://www.qualtrics.com Redcap Project. http://Project-redcap.org

Reuben, A., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Belsky, D. W., Harrington, H., Schroeder, F., Hogan, S., Ramrakha, S., Poulton, R., & Danese, A. (2016). Lest we forget: Comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(10), 1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12621

Rich-Edwards, J. W. (2006). Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 60(3), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.039370

Sanchez, S. E., Islam, S., Zhong, Q.-Y., Gelaye, B., & Williams, M. A. (2016). Intimate partner violence is associated with stress-related sleep disturbance and poor sleep quality during early pregnancy. PLOS ONE, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152199

Sedov, I. D., Cameron, E. E., Madigan, S., & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M. (2018). Sleep quality during pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 38, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.005

Sharkey, K. M., Boni, G. M., Quattrucci, J. A., Blatch, S., & Carr, S. N. (2016). Women with postpartum weight retention have delayed wake times and decreased sleep efficiency during the perinatal period: A brief report. Sleep Health, 2(3), 225–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2016.05.002

Slade, A., Holland, M. L., Ordway, M. R., Carlson, E. A., Jeon, S., Close, N., Mayes, L. C., & Sadler, L. S. (2019). Minding the Baby ®: Enhancing parental reflective functioning and infant attachment in an attachment-based, interdisciplinary home visiting program. Development and Psychopathology, 32(1), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579418001463

Spinelli, M. G., & Endicott, J. (2003). Controlled clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus parenting education program for depressed pregnant women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(3), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.555

Takelle, G. M., Muluneh, N. Y., & Biresaw, M. S. (2022). Sleep quality and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care unit at Gondar, Ethiopia: A cross- sectional study. BMJ Open, 12(9). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056564

Talari, K., & Goyal, M. (2020). Retrospective studies – Utility and caveats. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 50(4), 398–402. https://doi.org/10.4997/jrcpe.2020.409

Vafapoor, H., Zakiei, A., Hatamian, P., & Bagheri, A. (2018). Correlation of sleep quality with emotional regulation and repetitive negative thoughts: A casual model in pregnant women. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, In Press. https://doi.org/10.5812/jkums.81747

Vandekerckhove, M., & Wang, Y.-lin. (2017). Emotion, emotion regulation and sleep: An intimate relationship. AIMS Neuroscience, 5(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3934/neuroscience.2018.5.1

van den Heuvel, M. I., Johannes, M. A., Henrichs, J., & Van den Bergh, B. R. H. (2015). Maternal mindfulness during pregnancy and infant socio-emotional development and temperament: The mediating role of maternal anxiety. Early Human Development, 91(2), 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.12.003

Walker, M. P., & van der Helm, E. (2009). Overnight therapy? the role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 731–748. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016570

Wallace, K., & Araji, S. (2020). An overview of maternal anxiety during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Journal of Mental Health & Clinical Psychology, 4(4), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.29245/2578-2959/2020/4.1221

Wilson, H., & Donachie, A. L. (2018). Evaluating the effectiveness of a dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) informed programme in a community perinatal team. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 46(5), 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1352465817000790

World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/