Social and Behavioral Science

129 Religious Trauma Effects on LGBTQ+ Individuals in the LDS Context

Kathryn Howard

Faculty Mentor: Lisa Diamond (Psychology and Gender Studies, University of Utah)

Abstract

In recent years, there has been more discussion around the trauma and trauma responses that come from being a queer individual (one who identifies with members of the LGBTQIA+ community) inside a high-demand religion that does not affirm existence or behaviors of LGBTQ+ individuals. Emerging literature suggests that existing in an environment where, as a queer individual, one inherently does not feel respected or safe can lead to depressive, CPTSD, and scrupulosity symptoms, as well as significantly detract from feelings of social safety (Christensen, 2022). Lower sense of self-worth, relationship conflicts with family, the church, and a higher power, depression, and in severe cases, suicide, can all be consequences of existing in these kind of environments as a queer person (Bradshaw, 2015). However, previous research has failed to fully measure the effect that the timing and length of participation and membership in these religious institutions have on the severity and symptomatology of the trauma experienced.

This study is a follow-up from one conducted in December of 2021, which looked specifically at queer individuals in the LDS church (Latter Day Saints). The same participants were contacted to measure any changes from two years ago. In addition to this, the survey was also open to new participants. The new survey included questions that were not asked in the first survey but have proved themselves relevant. This included asking more questions about the amount of time spent in the LDS church and how devoted the individual was during these times. This line of questioning was undertaken so one can see how timing and duration correlates with trauma symptomatology.

There was a total of 1214 respondents, with a mean age of 29.9 (SD = 7.72). In all, 47.8% were assigned male at birth, 52.2% were assigned female, and 17.8 % had a gender identity different from their birth-assigned gender. Regarding church activity, 64% reported that they remained active in the church at least once a week.

Through these questions it was found that the duration spent in the church significantly correlated with rates of OCD symptoms, and lack of social safety for those in their twenties and younger, and that duration spent in the church was significantly positively correlated with depressive symptoms regardless of age.

INTRODUCTION

It is no secret that religion and queerness often do not mesh well together. However, sometimes it is more than just “not getting along.” When assessing homonegativity, which is defined as the disapproval of homosexuality, one study found that the biggest predictor of this variable in individuals was their theological orientation (Village & Francis, 2008). Being queer and surrounded by messages that instill negativity about the very core of a person can have tremendous negative impacts on an individual, especially in regards to their mental and emotional health (Page et al., 2013).

High-demand religions are defined as religions that involve large time and resource commitment, stresses scriptural and leadership infallibility, contain a certain level of separation between the members “worldly people” and have strict, enforced rules and codes, especially those about one’s diet, wardrobe, education, sex and reproduction, marriage and relationships, use of technology, language, and social involvement (Myers, 2017). One high-demand religion where this is particularly true is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS). In some cases, the constant barrage of religious messages can result in the development of religious trauma. Religious trauma is defined as “a group of symptoms that arise in response to traumatic or stressful religious experiences,” (Kingdon, n.d.). While this is a very broad definition with many interrelated variables falling under its scope, religious trauma is becoming increasingly prevalent amongst the LGBTQ+ population (Hollier et al., 2022). In 2018 a study showed that the more LGBTQ+ members attend church services, the more mentally unhealthy they were (Finn, 2019).

“Homosexuality is an ugly sin, repugnant to those who find no temptation in it…..All such deviations from normal, proper heterosexual relationships are not merely unnatural but wrong in the sight of God,” (Kimball, 1969). This is a direct quote from Spencer W. Kimball, not only a prolific Latter Day Saint Church leader, but the president of the LDS church at the time. With such strong views of condemnation being expressed in these teachings, it is not surprising to see that religious trauma is more prevalent among queer people.

One potential outcome of religious trauma is Scrupulosity OCD, which is a subtype of OCD in which one develops “religious or moral obsessions” (IOCFD 2010). Most people are familiar with the type of OCD that causes obsessive hand washing as well as numerical obsessions. Clearly, washing your hands is a good thing, but once it crosses a certain threshold, it is no longer helpful but can prove to have negative effects on one’s mental and physical health.

One of the best treatments for this is exposure therapy where one is forced to not wash their hands, so they can see that nothing catastrophic happens. This therapeutic process allows the individual to change their relative perspective on reality, helping them embrace the uncertainty of the world.

This situation mirrors a less well-known subtype of OCD. The rigorous hand washing is replaced with praying, repenting, scripture reading, and/or another religious or moral fixation. Such fixations can reach a degree of harmful behavior, just as the aforementioned issue with the hand washing where one finds themselves unable to leave their home, and sometimes, their church (Albińska, 2022). Can doing these activities be a good thing? Absolutely. They can bring peace of mind to people if that’s what they believe. But, just like hand washing, it can reach a point where it is no longer helpful, and that needs to be addressed (McIngvale et al., 2017).

A study was conducted by Fergus and Rowan in 2014, which was inspired by the lack of research in the field of psychology with the scrupulosity subtype of OCD. This disorder is often found to have strong correlations with religious trauma; there is a volatile relationship of uncertainty that is correlated to this disorder. “Difficulties tolerating uncertainty are considered central to anxiety disorders” (Fergus & Rowatt, 2014). For queer individuals in the LDS church, there is a considerable amount of uncertainty. There is uncertainty of whether or not your feelings are valid, how your family will react, how your bishop will react, and the biggest uncertainty of all – no one can truly answer how god will react (Brandley, 2020). This bolsters the idea that queer individuals are more likely to develop scrupulosity and other anxiety disorders when inside the LDS church due to the uncertainty that it creates. This is why many argue for the need to bring further attention to this issue, specifically (Allen et al., 2015).

In most religions, the LDS church being no exception, the idea of God being a perfect being is taught. Because of this, many people are trained to blame themselves when these issues begin persisting, thinking it is because they are not praying enough or not living a fully righteous life. For those in the LGBTQ+ community, this often turns into the phenomenon of “praying the gay away” that many people go through (Ashworth, 2022). There are countless stories of Mormon kids denying their sexuality and feeling increasing shame as they grew up and discovered where their sexual desires lay. As this shame gets internalized, it starts to spread to every part of one’s life. When you start to believe that who you are is simply wrong or a sin, your self-esteem may start plummeting (Joseph, 2017). Low self-esteem is correlated with depression, eating disorders, suicidal ideation, anxiety, etc. It is also correlated with the development of OCD (Afifi, 2022).

Ghafoor and Mohsin (2013), in an effort to identify the relationship between religiosity, guilt, and self-esteem for those with OCD, conducted a study and wrote a corresponding article. They are quoted as saying, “that there is an inverse relationship between self-esteem and religiosity and OCD.” This clarifies that the two do in fact have some correlation and more research needs to be done to study this relationship (Ghafoor & Mohsin, 2013).

This religious trauma among the LGBTQ+ community often leads to internalized and sometimes even outwardly expressed homophobia. Internalized homophobia presents itself when an individual is surrounded by a group’s negative views, stereotypes, and stigmas regarding LGBTQ members and relationships (Gill & Randhawa, 2021). Many people in these cultures, religions, or families begin to take those ideas and turn them inward and become convinced that they must be factual. This often results in self-hatred and denial of one’s true self. In fact, it was even found that there was little difference in internalized homophobia between denominations that were very traditional and those that painted themselves as “more accepting.” It was found that the less queer individuals attended these meetings, the less internalized homophobia they exhibited, and the better their mental health was. The severity and prevalence of this phenomenon for queer individuals is even stronger among those that also belong to minority groups, especially Black and Latinx individuals (Barnes, 2013).

A group of researchers led by Caitlin Pinciotti (2022) recognized that, like other minorities, those in the LGBTQ+ community are subject to minority stress because of all these different forms of homophobia. They also could see that many times OCD developed by these individuals often, “inadvertently reinforces anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) stigma and contributed to minority stress in clients, treatment providers, and society at large” (Pinciotti et al., 2022). In their conclusion, they emphasized that a big way to help in the treatment is to “eliminate exposure to minority stress.” Minority stress is experienced in incredibly high levels by queer people in the LDS church (Kehller, 2009). This can be very detrimental to the treatment of those queer individuals with OCD.

Religious trauma can also present itself in simple decisions of everyday life. Having a religion that makes so many of your decisions for you and warns you of the consequences of making the wrong ones can result in paralyzing fear. This is especially true for those in the queer community who have already been taught that they cannot trust themselves and their instincts. Nitisco (2021), a clinical psychologist and researcher, examined the phenomenon of OCD and decision making and found that, “decision-making has been proposed to have a central role in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) etiology, since patients show pathological doubt and an apparent inability to make decisions” (Nisticò et al., 2021). Combining the research of the past decade, she further explores how this symptom can be debilitating. Here we can see yet again how this can easily make the LDS church environment an easy place to foster OCD symptomatology.

The seemingly most obvious solution to this issue is for those affected to simply leave the religion or not join it in the first place. Unfortunately, it is never quite that easy. A lot of people are born into it without any choice or say in it. It then becomes all they know. Not only that, but it can serve as a foundation of their families or communities, so leaving the religion also means leaving any social support they have ever known. This is especially true of high demand religions. There are many stories of people leaving the church after attending Brigham Young University, an LDS university, and losing their job, friends, academic scholarships, important familial relationships, structured social events, etc. Often it is easier for people to intellectually understand that they don’t believe in a certain religion and their teachings, especially when it comes to social issues, but when it comes to the emotional aspects of these same processes, it becomes increasingly more difficult (Winell, 2021).

A very publicized case of this regarding the queer community and the LDS religion is that of Josh Weed. He grew up in the Mormon church and was also openly gay. Most likely due to some of the reasons mentioned earlier, he decided to stay in the religion. Not only that, but because he had also been taught that marriage in the temple is essential, he ended up marrying and having children with a straight woman. He didn’t do this in the more common way where he hid his identity and tried to deny it. Both he, his wife, and everyone involved knew he was gay, and she wasn’t. He became the poster child in the LDS church for how one could overcome the “sin” of homosexuality. He and his family lived this way for many years, they had four children, and claimed to be happy with their choice to live in “righteousness,” but in 2018 things came to a turning point. On January 25, 2018, the seemingly happy couple declared that they were getting a divorce. Through Josh’s blog, many people got to see firsthand how this deconstruction took place. Josh listed many things that had been taught to him by religious leaders, therapists, and mentors that created cognitive dissonance. He, like many others, was told that his sexual orientation was a trial, evil, not even real, something to be endured, something that could be changed in this life or the next. This kind of psychological discomfort is something that is experienced all too often, but not widely studied. This present study will work to close some of the gaps in the literature.

Although some people do leave these churches, there is still trauma to be worked through. But the question is, just how much? One participant during the first survey made the comment while completing the questionnaire that, “The impacts of being indoctrinated from birth for 14-15 years has impacted my whole adult life” (Christensen, 2022). This begs the question of what happens when someone is in the church well into their middle age? Or how does it affect someone who leaves before they hit their teen years? It is hypothesized that the longer a queer person spends experiencing conflict between their sexuality and their church membership, the more OCD, depression, and other religious trauma symptoms they will exhibit, unless they successfully exit from the church.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited through online advertisements (described in detail below). Inclusion criteria included (1) being 18 years of age or older (2) identifying as LGBTQ+ or same-gender attracted, and (3) identifying as a current or former member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. After excluding participants who declined to provide information on the age at which they were most concerned about being Mormon and LGBTQ+, we had a total of 1214 respondents, with a mean age of 29.9 (SD = 7.72). In all, 47.8% were assigned male at birth, 52.2% were assigned female, and 17.8 % had a gender identity different from their birth- assigned gender. Regarding church activity, 64% reported that they remained active in the church at least once a week. Demographic information on the sample can be viewed in Table 1 (see Appendix).

Measures

For the purposes of this paper, the measures that were used were the CESD-R Depression scale (Eaton, Smith, Ybarra, Muntaner, & Tien, 2004), the Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity (PIOS; Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin, & Cahill, 2002), the Social Safety Scale (Diamond, 2023), the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory Scale (OCI) (Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles, & Amir, 1998), a revised version of the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS) for the assessment of religious trauma (Bride, Robinson, Yegidis, & Figley, 2004), and self-report measures of the duration of individuals’ experience of conflict between their sexual/gender identity and the church.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R)

This scale is designed as a 20 question, self-report scale that aims to quantify depressive symptoms. After many tests it has been found to have strong internal consistency as well as validity and repeatability. The scale assesses common symptoms of depression such as feelings of guilt or worthlessness, changes in appetite, poor sleep quality, depressed mood, etc. The participants are asked how often they feel said items and have options ranging from “rarely or none of the time” (0), to “most or all of the time” (4). The Cronbach’s alpha for the CES total scales was 0.90 and the mean for this sample was 24.3 (SD=12.75). Scores between 16-23 are typically interpreted as indicating moderate depressive symptomatology whereas scores greater than 24 are interpreted as indicating severe depressive symptomatology (Radloff, 1977).

Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity (PIOS)

This measure is split into two subscales which are the Fear of Sin and Fear of God. It is a self-report scale containing 19 items and is used to measure religious obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Each question is responded to on a five-point scale, with frequency items ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (constantly), and distress of symptoms items rated from 0 (not at all distressing) to 4 (extremely distressing) (Abramowitz et al, 2002). Cronbach’s alpha has been calculated at α=0.94 for this measure in the study. The mean was calculated at 36.8 (SD=11.74). Social Safety

The Social Safety Questionnaire asks participants to report on their social experiences within 7 different social domains: household, family, close friends, work/school colleagues, one’s most important identity group, members of the LDS church, people in public spaces, and people known through social media. For each setting, participants rated on a 1-5 scale how often they (1) looked forward to seeing the people there, (2) felt certain about how things would go, (3) felt that others would notice or care if they were sick or hurt, (4) felt so comfortable that they didn’t notice time passing, (5) saw or heard something that made them feel affirmed, (6) felt that they mattered to the people there, (7) felt they could say “no” to these people, (8) felt there was someone in this setting they could turn to for help, (9) felt so secure that they stopped paying attention to how others perceived them, (10) felt that they were treated and spoken to the way they wanted, (11) were made to laugh or feel good by others, (12) felt like their real self, and (13) experienced joy and pleasure. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .84 to .95 for each separate domain, and reliability for the total social safety score (averaged across all domains) was .95. Mean social safety was 3.09 (SD = .47).

Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale (STSS)

The STSS is made up of 17-item self-report measures. It is designed to measure PTSD- related symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, and arousal. The questions are scored on a five-point Likert-like scale, each ranging from “never” (1) to “very often” (5), indicating how often symptoms were felt in the last week. Items were summed for this study. Though the symptoms measured are generally associated with secondary traumatic stress, Simmons (2017) determined that this would provide enough sensitivity to measure the impacts of both unintentional and intentional traumatic experiences, only modifying it to refer better to one’s religious experiences and finding high internal reliability for his sample. This modified version was the one used in the present survey. We calculated Cronbach’s alpha to be α=0.81 for this measure. The mean was calculated at 59.33 (SD=5.51).

Obsessive Compulsive Inventory Scale

The OCI, Obsessive Compulsive Inventory, Scale is a self-report measure used to assess the severity of OCD symptoms. The OCI scale consists of 18 items that assess various aspects of OCD symptoms, including checking, washing, obsessing, hoarding, and ordering. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The total score on the OCI scale ranges from 0 to 72, with higher scores indicating greater severity of OCD symptoms. The OCI scale is a commonly used and well-validated measure for assessing OCD symptoms in clinical and research settings. Cronbach’s alpha has been calculated at α=0.96 for this measure in the study. The mean was calculated at 44.0 (SD=22.79). A score of 28 is typically interpreted as indicating the presence of OCD.

Duration of Concern

The questionnaire asked individuals to report the age at which they felt the most concern about being LGBTQ+ and Mormon. The mean age of greatest concern was 17.88 (SD = 5.1). We subtracted this age from participants’ current age to estimate the length of time they experienced concerns about being LGBTQ+ and Mormon. The mean duration of concern was 12.0 years (SD = 7.5).

Procedure

Participants who encountered online advertisements of the survey were instructed to contact the investigators via email or to visit the study website (www.matteringmatters.net) which provided more information about the study and also included a direct link to participate. The survey began with the IRB-approved consent form, and participants indicated their consent by clicking at the bottom of the form to progress to the survey. Participants were sent a $40 gift card after completing the survey. Six percent of participants chose to donate their gift card to other participants.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted with multivariate regression analysis in SPSS. All continuous predictor variables were centered before entry into the regression model, and all dichotomous variables were dummy coded.

RESULTS

For the multivariate regression analysis, the outcome variables were depressive symptoms, scrupulosity, religious trauma symptoms, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and social safety. The predictors were participants’ current age, their birth-assigned gender, the duration of their concerns with being LGBTQ+ and Mormon, and whether they currently remained active in the church. The results indicated that individuals who had spent more years feeling concerned about being LGBTQ+ and Mormon reported significantly higher levels of depression (b =.45, p <

.001), higher obsessive-compulsive symptoms (b = .45, p < .001), and lower social safety (b = –.01, p = .006), but there was no association between duration of concern and participant’s religious trauma symptoms (b= -.01, p = .10) or their scrupulosity (b = .01, p = .62). We then conducted exploratory tests for interactions between duration of concern and the other variables in the model (age, gender, and current membership status). We found significant interactions between participant’s age and participant’s duration of concern for scrupulosity (b =

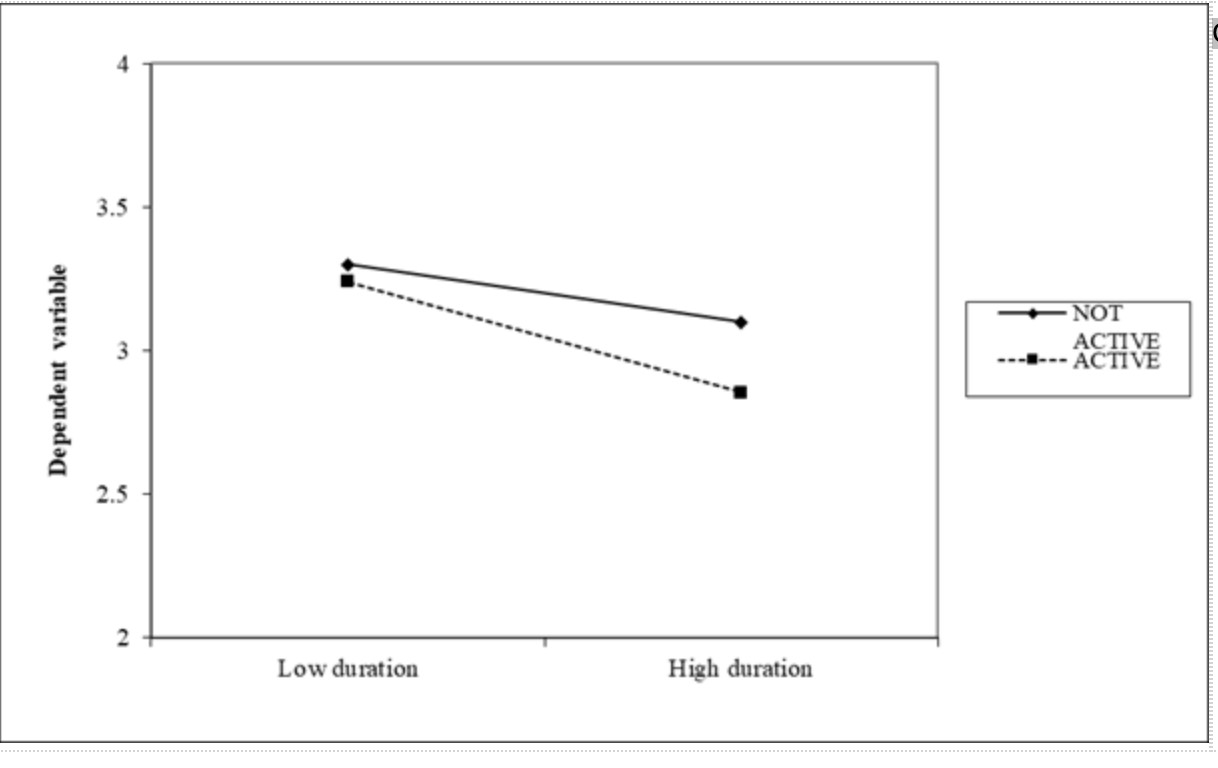

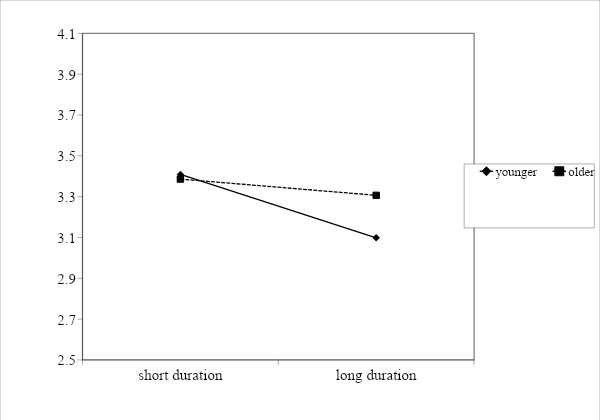

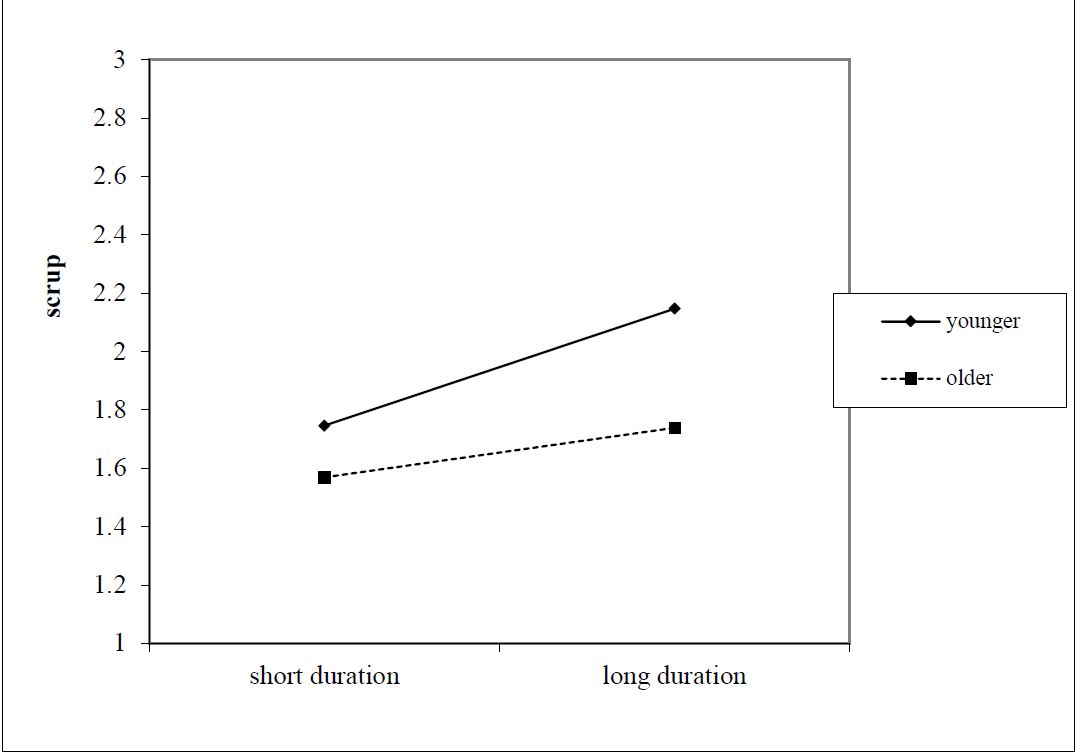

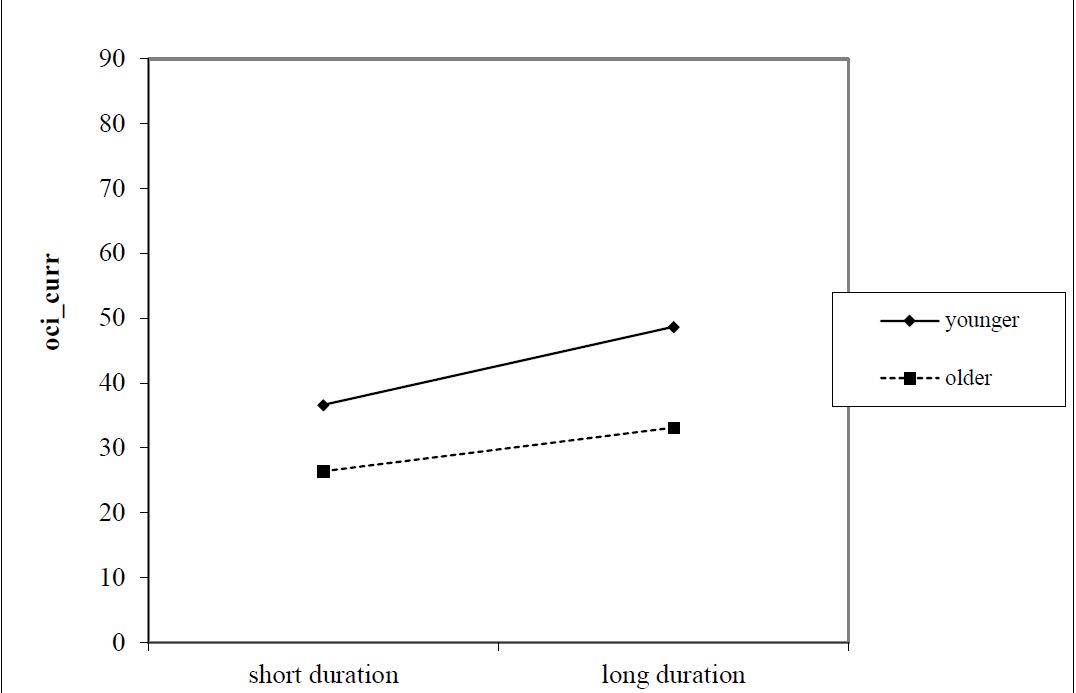

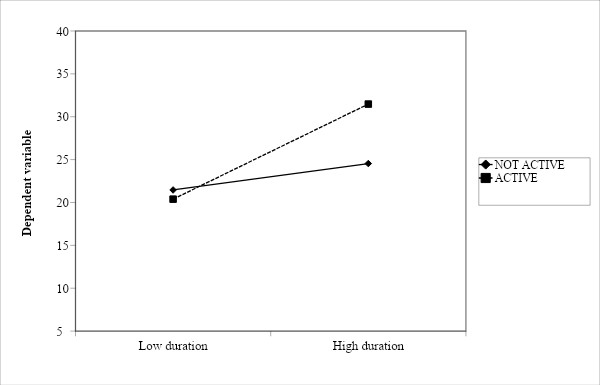

-.01, p < .001), social safety (b = .01, p < .001), and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (b = -.023, p < .001), and we found significant interactions between participant’s current church activity and their duration of concern for depression (b = .376, p < .001) and social safety (b = -.012, p <.001). These interactions can be seen in Figures 1-5 (see Appendix).

Follow-up simple slope tests (estimated at one standard deviation above and below the sample mean for age) revealed that among younger participants (those in their early 20’s), participants’ duration of concern was significantly associated with higher scrupulosity, b = .02, p< .001, whereas duration of concern was not significantly associated with higher scrupulosity among older participants (those in their late 30’s or older; b = .01, p = .10). For social safety, simple slopes tests revealed that duration of concern was more strongly associated with lower levels of social safety among younger than older participants (byounger = -.03, p < .001, bolder =-.01, p < .001). This can be seen in Figures 1 and 2 (see Appendix).

Similarly, for obsessive-compulsive symptoms, duration of concern was more positively associated with obsessive-compulsive symptoms among younger than older participants (byounger= .80, p < .001, bolder =.42, p < .001). This can be seen in Figure 3. (see Appendix).

With respect to church activity, duration of concern was more strongly positively associated with depressive symptoms among individuals still active in the church (b = .71, p <.001) than among individuals no longer active (b = .20, p = .03), and duration of concern was negatively associated with social safety only among active church members (bactive = -.02, p <.001, binactive = -.001, p .43). This can be seen in Figures 4 and 5 (see Appendix).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this research was to study the impact of religious trauma (specifically, OCD symptoms related to the LDS faith) and social safety on the mental health complications that many individuals who identify as part of the LGBTQ+ community and belong to the LDS faith report. The present study specifically aimed to explore the associations between duration of time spent in the LDS faith and the severity of OCD and other mental health symptoms.

The hypothesis proposed was that the longer duration a queer individual had in the LDS church, the more scrupulosity OCD symptoms they would report. The findings align with both this hypothesis and prior literature on the subject as discussed in the introduction; however, the correlation was only found in younger participants. This may suggest that those younger participants with a longer duration may require a different type of intervention than those with a short duration, or those with a longer duration but who are older. This could be due to the importance of developmental years on an individual’s brain and sense of self (Goldback & Gibbs, 2017).

The second hypothesis suggested that the longer the duration a queer individual had in the LDS church, the more depressive symptoms would be present. The findings supported this hypothesis as well. It also makes sense when compared to prior literature which suggests that “stress from hiding and managing a socially stigmatized identity” can be a risk factor for depression (Hall, 2018). This idea is related to that of social safety as well. The findings also supported the idea that less social safety would be reported the longer the individual spent in the church.

Altogether, the results of this study suggested that individuals who encountered more religious beliefs and teachings for an extended period of time experienced higher levels of

religious trauma. Additionally, exposure to harmful religious teachings/beliefs was a significant predictor of scrupulosity OCD symptoms, depression, lack of social safety and overall worse mental health outcomes. It is likely that the harmful effects of these religious teachings on people’s health is a direct result of the trauma that these teachings can often induce.

This study’s results are consistent with previous research, including research released by Simmons in 2017 that found a connection between exposure to harmful beliefs/teachings in the LDS religion and religious trauma. The study conducted for this paper went even further, discovering that religious trauma is correlated with worse mental health, thus connecting the two areas of literature.

Many of these findings were the same as were found in the previous study (Christensen, 2022). However, this extension of the study also found a high correlation between duration spent in the church with the severity of religious trauma symptomatology. This implies that there may be a need for specific interventions designed for individuals who have been in the LDS church and experienced religious trauma for an extended period of time.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study has many strengths, there are a few limitations that are important to note. One limitation is the use of convenience sampling, which may limit the generalizability of the results to the population of interest (LGBTQ+ individuals with past or present membership within the LDS church). Another limitation is the fact that the study is essentially retrospective, as respondents were asked to consider the impact of past events. This may affect the accuracy of responses as people’s memories are not always 100% accurate (Gloster et al., 2008). Future studies should be mindful of this and potentially have a way to report during this experience instead of after.

The lack of a control group that is made up of heterosexual and gender conforming LDS members also limits the ability to determine the full impact of LDS participation on LGBTQ+ members. Future studies should include a control group to increase the validity of results. A third limitation is the fact that the survey was long enough (60-120 minutes) that some participants didn’t finish, so the data we got was just based on people that had the time and resources to commit to starting and finishing the survey. Those who do future research on this topic may want to consider that factor when they decide on a form of data collection.

Despite these limitations, the study found that more time spent within the LDS church predicted worse mental health outcomes, and having spent less time exposed to this is associated with better mental health outcomes. An alternative explanation may be that people with greater mental health might have felt more empowered to leave sooner; however, more research is needed to fully analyze this possibility.

These findings have important implications, suggesting the need for greater support for members of the LDS church who identify as LGBTQ+ individuals, especially those who are still active in the church and those who have or are spending an extended period of their time in life participating in the church. Further research is necessary to explore and test these implications.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations mentioned above, the study yielded significant results that have important implications for many LDS and queer communities. One of the biggest ones is that many LGBTQ+ individuals in the LDS church have been exposed to harmful teachings and beliefs, which have led to trauma that is associated with negative mental health outcomes such as depression, scrupulosity, and poor general health.

The study also found that having spent a longer amount of time in the LDS church intensifies the severity of symptoms experienced, including scrupulosity OCD, depression, and other health outcomes. This may imply that those having spent more time may require a different or more intensive approach to treatment. Further research is required to validate and expand upon these implications.

REFERENCES

Afifi, D. Y., Shahin, M. O., Alaa, Y., & Ayoub, D. R. (2022). Investigation of Symptom Severity, Self-Esteem, & Suicidality in Anxiety Disorders and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología Del Ejercicio y El Deporte, 17(6), 380–386.

Albińska, P. (2022). Scrupulosity — cognitive-behavioural understanding of religious/moral obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna (Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psychology), 22(1), 25–39. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.15557/PiPK.2022.0004

Allen, G. E. K., Wang, K. T., & Stokes, H. (2015). Examining legalism, scrupulosity, family perfectionism, and psychological adjustment among LDS individuals. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 18(4), 246–258. https://doi- org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1080/13674676.2015.1021312

Ashwortth, K. (2022, February 5). In My Own Words – Latter Gay Stories Podcast. Latter Gay Stories Podcast. https://lattergaystories.org/inmyownwords/

Avance, R. (2013). Seeing the light: Mormon conversion and deconversion narratives in off- and online worlds. Journal of Media and Religion, 12(1), 16-24. doi:10.1080/15348423.2013.76038

Barnes, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2012). Religious affiliation, internalized homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. The American journal of orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-

0025.2012.01185.

Brandley, B. (2020). “This is How You Navigate the World”: Impacts of Mormon Rhetoric on White Queer Members’ Identity Performances. University of New Mexico Digital Repository.

Foa, E. B., Kozak, M. J., Salkovskis, P. M., Coles, M. E., & Amir, N. (1998). The validation of a new obsessive–compulsive disorder scale: The Obsessive– Compulsive Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 10, 206-214. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.3.206

Gill, S., & Randhawa, A. (2021). Internalised Homophobia and Mental Health. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing, 12(4), 501–504.

Gloster, A. T., Richard, D. C. S., Himle, J., Koch, E., Anson, H., Lokers, L., & Thornton,

J. (2008). Accuracy of retrospective memory and covariation estimation in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 46(5), 642–655. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.010

Goldbach, J. T., & Gibbs, J. J. (2017). A developmentally informed adaptation of minority stress for sexual minority adolescents. Journal of adolescence, 55, 36–

50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.007

Hall, W. J. (2018). Psychosocial Risk and Protective Factors for Depression Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Queer Youth: A Systematic Review. Journal of Homosexuality, 65(3), 263–316. https://doi- org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1080/00918369.2017.1317467

Hollier, J., Clifton, S., & Smith-Merry, J. (2022). Mechanisms of religious trauma amongst queer people in Australia’s evangelical churches. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(3), 275–285. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1007/s10615- 022-00839-x

Joseph, L. J., & Cranney, S. (2017). Self-esteem among lesbian, gay, bisexual and same- sex-attracted Mormons and ex-Mormons. Mental Health, Religion & Culture,

20(10), 1028–1041. https://doi- org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1080/13674676.2018.1435634

Kelleher, C. (2009). Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070903334995

Kimball, S. L. (1969). The Miracle of Forgiveness. Bookcraft, Salt Lake City. Kingdon. (n.d.). Religious Trauma & Transitions — RESTORATION COUNSELING.

RESTORATION COUNSELING.

https://www.restorationcounselingseattle.com/religious-trauma- transitions#:~:text=Religious%20Trauma%20Syndrome%20(RTS)%20is,traumati c%20or%20stressful%20religious%20experiences.

McIngvale, E., Rufino, K., Ehlers, M., & Hart, J. (2017). An In-Depth Look at the Scrupulosity Dimension of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 19(4), 295–305. https://doi- org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1080/19349637.2017.1288075

Myers, Summer Anne, “Visualizing the Transition Out of High-Demand Religions” (2017). LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations. 321. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd/321

Page, M. J. L., Lindahl, K. M., & Malik, N. M. (2013). The Role of Religion and Stress in Sexual Identity and Mental Health Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Wiley-Blackwell), 23(4), 665–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12025

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385-401

Village, A., & Francis, L. J. (2008). Attitude Toward Homosexuality among Anglicans in England: the Effects of Theological Orientation and Personality. Journal of Empirical Theology, 21(1), 68–87. https://doi- org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1163/092229308X310740

Zhang, Y., Qu, B., Lun, S., Guo, Y., & Liu, J. (2012). The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey: Reliability and Validity in Chinese Medical Students. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(7), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.4503

APPENDIX

Figure 1

Interaction duration of period of greatest concern (PGC) and age on social safety

Figure 2

Interaction between duration of period of greatest concern (PGC) and age on scrupulosity

Figure 3

Interaction between duration of period of greatest concern (PGC) and age on OCD

Figure 4

Interaction between duration of period of greatest concern (PGC) and current church activity on depression

Figure 5

Interaction between duration of period of greatest concern (PGC) and current church activity on social safety