College of Humanities

76 Breaking the Circle: Puerto Rico After Hurricane Maria

Joseph de Lannoy

Faculty Mentor: Gema Guevara (World Languages and Cultures, University of Utah)

My research, Breaking the Circle, is an intersectional analysis of Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria (Maria). I will examine colonial US rule legislation such as the Jones Act signed in 1917 gave Puerto Ricans US citizenship and draft eligibility, Act 22 a tax incentive law specifically for non-Puerto Rican individuals and businesses, and PROMESA an unelected board which has complete oversight over the repayment of Puerto Rico’s sizable debt to the United States. Studying the Jones Act alongside more modern legislation like Act 22 and PROMESA highlights the deep-rooted political relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico. The Jones Act, Act 22, and PROMESA all have a similar goal: to perpetuate US colonial influence over Puerto Rico. These legislations paired with environmental injustice created a political landscape that led to the displacement of Puerto Ricans on the island and a complete disruption of traditional patterns of migration known as el vaiven or circular migration (Duany 2002). While the title of this paper specifically indicates the disruption of the traditional circular migratory pattern between Puerto Rico and US, this paper seeks to highlight the historical issues which Puerto Ricans have faced from their colonial relationship with the United States and the shortcomings of the colonial systems and connect them to Hurricane Maria a catastrophic environmental disaster that only brought to the surface these institutional issues which resulted in the colonial necropolis seen today. I examine the issues that Puerto Ricans face due to their colonial relationship with the United States. These issues have been present since the establishment of the colony, with Hurricane Maria serving as a watershed event exacerbating them further resulting in environmental injustice, socioeconomic inequality, and mass displacement of individuals. Puerto Ricans have essentially become a second-class citizenry.

I will briefly discuss these legislative acts because they assisted in the creation of the current political climate which prioritizes US control and the perpetuation of colonial rule resulting in second class citizenry. The Jones Act bestowed Puerto Ricans US citizenship and draft eligibility. This act gave Puerto Ricans some autonomy in terms of governance and legislation, but they remain completely under US authority and rule. This act serves as the foundation of the legal and economic dependency between the United States and Puerto Rico. Similarly, the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) was signed and mandated into law by President Barack Obama to oversee the payment and management of Puerto Rico’s sizable debt of around 72 billion in 2015 (Mora 2019). PROMESA, locally known as La Junta, has cut spending in all public sectors with the goal of paying back this debt. PROMESA jeopardizes Puerto Rico’s sovereignty as a Free-Associated State because La Junta has been given full power over the management of Puerto Rico’s funding and in the 2023 court ruling of Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico v. Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, La Junta was granted sovereign immunity. This means that PROMESA has unrestricted power over the island territory’s budget. Finally, Act 20, also known as the Export Services Act, incentivizes foreign businesses (more frequently mainland United States businesses) or individuals who have a high income to bring their assets to the island in hopes of stimulating the local economy. These incentives, however, are specifically for non-Puerto Ricans, and following the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, they were used by many developers and property owners who purchase substantial amounts of property on the island resulting in the displacement of many Puerto Ricans. The inclusion of these legal precedents serve to support my claim that because of local and federal mismanagement and outright political exploitation, the social, political, and economic inequalities seen on the island will only increase if the current trends are to continue.

Puerto Rico, following the ratification of the Puerto Rican constitution in 1952 was given the status of a Free-Associated State or Estado Libre Asociado which means that the island is given cultural and some economic sovereignty but remains under the direct governance of the United States. This makes Puerto Rico an anomaly not only in Latin America but among other nations. This relationship defines the political landscape on the island. The social, political, and economic relationship with the United States laid the foundation for the current situation on the island. Puerto Rico is situated geographically in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean, which makes it prone to natural disasters like hurricanes and tropical storms. Hurricane Irma, which preceded Maria, ravaged islands neighboring Puerto Rico. While the storm did not make landfall on the island, the winds and power-outages still impacted local infrastructure and was harbinger of the decimation which was to come. Puerto Rico’s dependence socially, economically, and politically on the United States paired with its vulnerability to natural disasters left the island with an uncertain future.

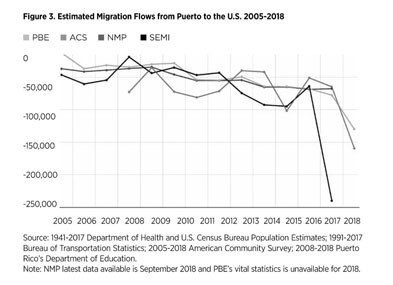

The title of this paper, Breaking the Circle, is centered around circular migration, and how the disruption of this pattern has only exacerbated further the feelings of uncertainty that currently surround Puerto Rico’s future. Jorge Duany coined the term, circular migration to describe the coming and going of Puerto Ricans from the US and the Island. This type of migration is a bit of an abnormality for other Latinx groups who have similar-sized communities in the United States. Puerto Ricans following the Jones Act granting US citizenship and the Great Migration of the 1950s have come and gone from Urban centers such as New York City in a circular or seasonal manner (Duany 2002). This type of migratory movement between the two territories resulted in what we typically understand to be a transnational nation. Puerto Rico serves as the cultural and familial home while places such as New York City served as a temporary home where Puerto Ricans sought better-paying jobs in industrial sectors. This created an exchange of goods, ideas, and individuals between the Island and the Continental United States. Around the 2008 housing crisis, there was a similar economic crisis on the Island. La Crisis Boricua or Puerto Rico’s severe economic crisis (Mora 2019) started around 2006 and ended around 2014 following several economic and political issues which led to a substantial drop in manufacturing jobs which resulted in Puerto Rico accruing a large national debt. This new economic instability laid the foundation for another large exodus, which could mirror or exceed the great migration of 1950. With the arrival of Hurricane Maria, there was mass economic and housing insecurity which resulted in an unprecedented exodus of Puerto Ricans to the US and a shift in the center of the Puerto Rican diaspora.

(Hinjosa 2018)

This figure highlights the mass exodus of Puerto Ricans to the United States following Maria in 2017. By 2019 were an estimated 600,000 Puerto Rican migrated to the continental United States. With these new migrants, the center of the Puerto Rican diaspora shifted from the State of New York to the State of Florida. Not only did Maria change the landscape of the Puerto Rican population on the Island, but it also upturned the historical trends of the diasporic communities on the United States mainland.

Hurricane Maria in its wake left many homes, businesses, and communities destroyed. This created a chasm in which two figurative Puerto Ricos emerged. One is where communities and families are looking to rebuild, and another is a clean slate for businesses and individuals looking to make a profit. In the documentary, Landfall (2019), this idea of two Puerto Ricos is explored in detail. One scene highlights a family in the mountains using their land to farm and rebuild while cryptocurrency billionaire Brock Pierce talks about the island being a place for economic opportunity and a haven of sorts for people like him. A journalistic piece done by a local news station, WAPA, titled Inversionismo del Desastre (2021) or disaster investment highlights the unequal purchasing of land on the island by developers who wish to capitalize on previously mentioned tax laws and economic and housing insecurity faced by Puerto Ricans. This emphasis on foreigners purchasing land in Puerto Rico is connected to the blank slate ideology that was used by the local Puerto Rican government immediately following Hurricane Maria to incentivize businesses and individuals who desired to come to the island and purchase land. (Whiteside 2019) The ideology of the phrase, “I live where you vacation” has been a marketing tactic paired with tax benefits that incentivized specifically mainland US citizens to move to Puerto Rico. This is unprecedented because historically Puerto Ricans have never been displaced on the island itself. Puerto Rico has been the cultural home for those on the island and in the diaspora. Because of the new laws and the disastrous effects of Maria, there has been a mass displacement of Puerto Ricans on the Island.

This reverse migration of sorts has been supported and encouraged by local and federal governments. The migration changes following Maria have been categorized by unprecedented changes to traditional patterns in terms of centers of migration, migration to the island, displacement of local communities, and a mass exodus of Puerto Ricans. The feelings of uncertainty by those participating in this mass exodus are beautifully captured in the song, In My Old San Juan which tells the story of a man leaving his island behind to seek better opportunities without the certainty of returning and being able to return. He says, “Adios Mi Borinken Querida” meaning, “Goodbye my beloved Borinken (the name of the island in the Taíno language).” This sentiment, which is frequently expressed in the diaspora that speaks to the loss of “home” as a metaphor of displacement, is now commonplace on the island following Maria.

The word incertidumbre is directly translated as uncertainty but carries a more ominous meaning. The concept of incertidumbre is not something easily quantifiable but it is the daily reality for many Puerto Ricans on the Island. While abstract, incertidumbre highlights the harsh reality of facing and recovering from environmental, social, economic, and political crises. The issuance of Act 20 and PROMESA have further deepened this feeling because they further exacerbated economic and political instability. The feeling of incertidumbre is connected to the ideas of space, place, and home. For those in the diaspora, incertidumbre comes from el vaiven the legal coming and going creates a transnational identity which for some, feelings of longing for their cultural home due to often forced separation because of economic insecurity. For Puerto Ricans on the island, the feeling of incertidumbre is connected to the uncertainty of the future of the Puerto they know and that which is yet to become. This idea of incertidumbre for those living on the island is explored clearly in the 2023 film titled La Pecera (The Fishbowl).

The protagonist Noelia serves as an incarnation of the generalized incertidumbre that prevails on the island. Noelia is diagnosed with late-stage colorectal cancer which is ravaging her body. We see Noelia, a Puerto Rican woman native to the Island of Vieques, suffering at her very core. Vieques served for many years as a US naval base for war games where live ammunitions and explosives were used. After years of protesting from the locals of Vieques, the US decided to abandon the naval base while leaving behind shrapnel, napalm, and polluted waters. The pollution left by the United States military has historically and presently been cleaned up by local groups. Noelia is one of these volunteers who has dedicated much of her life to cleaning up her polluted island. The cancer Noelia faces, and the cancer of colonial rule is a clear metaphor for the current situation on the Island. The film highlights Noelia’s journey in coming to terms with her sickness and it concludes before the arrival of both Hurricane Irma and Maria which are to arrive before Noelia’s death. I conducted an interview with the director of the film, Glorimar Marrero Sanchez, and I asked her if the incertidumbre felt throughout the film was intentional because of the film’s open ending, in which Noelia’s death or the arrival of Hurricanes Irma and Maria are not explicitly represented. Marrero responded by saying the uncertainty of Puerto Rico’s future and Noelia’s future are similar. Noelia as a character is an allegory for the island’s land and people. Her battle with cancer and the island’s battles with systemic issues of neoliberal colonial rule and pollution are similar because death is almost certain but not yet fulfilled. This film validates and highlights the incertidumbre felt by Puerto Ricans because they are unsure and unable to control their future in terms political and legal sovereignty, environmental injustice, and economic stability. Incertidumbre has been at the core of the Puerto Rican life, in diaspora and on the island, it drives people away from their homes in search of a stable future. Hurricane Maria only further exacerbated these feelings and was a catalyst for the calamities that ravaged an already precarious situation.

Hurricane Maria made landfall on the southwest coast of Puerto Rico on September 20th, 2017. Flooding, wind speeds of over 100 mph, and devastation to the already precarious electrical grid left many Puerto Ricans desolate. Some calculated the loss of life to be around two thousand people who died directly from the storm or because of the issues caused by the storm’s catastrophic wake. Maria is a watershed event that took away the tropical island’s beautiful exterior and laid bare the economic, environmental, social, infrastructural, and political issues that have historically plagued the island.

With the environmental destruction of the island, thousands of deaths, a decimated electrical grid, and a shortage of potable water, Puerto Ricans faced a harsh reality: to stay and rebuild or seek refuge in the continental United States. The island was in dire need of aid from the federal government and the slow economic and humanitarian response solidified what many Puerto Ricans already understood: they are not a priority for the United States Government. The current situation in Puerto Rico is a clear example of the intersection of political corruption, environmental injustice, legislation that has left the island environmentally vulnerable and opened to predatory economic practices especially in real estate and access to necessary resources.

Water regulation and potability have been at all-time lows making Puerto Rico the place in the United States with the worst rate of drinking water (Llórens 2019). Without access to necessary resources like usable water and electricity, people are left without options. The isolation from necessary resources was a common characteristic of post Maria life. The lack of shelter, water, electricity, and overwhelmed hospitals and public services only made worse the incertidumbre felt by those left in the wake of the storm. A physician who worked on the front lines of the relief effort described his feelings, and those of his cohorts as, “My residents were overwhelmed, not just from physical exhaustion but from our patients’ stories and the difficult decisions we had to make. We are not trained in disaster management, so we had to draw on our own personal and emotional strengths in managing the situation, aiming to provide high-quality and efficient care while maintaining our professionalism, humanism, and empathy” (Zorilla 2017). Not only did the lack of relief result in a destroyed electrical grid and widespread housing and economic insecurity, but it also overwhelmed and emotionally exhausted its physicians and medical staff. Similarly in the documentary Landfall, a woman describes the essence of life after Maria as the daily incertidumbre that they faced not knowing when or where help would be coming from. Some communities did not get power fully restored until a full calendar year after the storm. The local and federal governments failed them.

Puerto Rico before the storm had a sizable debt of around $72 billion in 2015.

This debt despite an unprecedented natural catastrophe remained the focal point for US interests and had increased to over $100 billion following the aftermath of Hurricane Maria (Mora 2019). This focus on the debt as a characteristic of the exploitative nature of the colonial relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. (Lloréns 2019). Llorens describes this relationship as “slow violence”. She describes this idea further as a “steady accumulation of gradual, and often invisible, environmental harms endures by vulnerable individuals and communities during capitalist expansion and neoliberalism” (Lloréns 2019). The US has leveraged its colonial power over Puerto Rico and its vulnerable populations by privatization of public services like energy providers, indifference toward pollution as seen by the pollution left by the military bases in Vieques, climate change, and gouging budgets all in the name of the repayment of Puerto Rico’s debt. This approach, however, is just a perpetuation of previous colonial models of extraction and isolation of colonial inhabitants. The post Maria environmental injustice, the house and economic insecurity crisis created a chasm on the island and figuratively. Out of this chasm, two Puerto Rico’s emerged. One where Puerto Ricans struggle for survival in the wake of environmental, social, economic, and political injustice; and another where those who are aligned with US interests see a chance for exploitation, privatization, and profit. While the coming and going of Puerto Ricans to the continental US is not a new phenomenon, but the circumstances of their arrival caused by forced displacement and permanent migration to the US in the post Maria era is groundbreaking. Lloréns describes Post Maria Puerto Rico as a failed colonial project and a necropolis. She argues,

The current historic exodus from the island also indicates that the contemporary political and economic model of the US territory has collapsed under the weight of neoliberal dispossession, shifting from the so-called Free-Associated State to a colonial necropolis of second-class citizens who can freely move to 50 US states, as a decade-long economic migration overlaps with climate change refugees whose very survival was at stake in the months after Hurricane Maria (Lloréns 2019).

Hurricane Maria was a watershed event that unearthed the already existing issues on the island connected to environmental injustice, political corruption, migration patterns, economic insecurity, resulting in a humanitarian, economic, housing, and social crisis due to the long-established colonial policies and structures. The shortcomings of local and federal governments to protect Puerto Ricans and support them following an environmental catastrophe served to only worsen the systemic issues which have resulted in the modern-day crisis seen on the island. This lack of support locally and federally only feeds into the reality of incertidumbre which is central to the lives of many Puerto Ricans. This paper contributes to Puerto Rican, Latinx, Caribbean, and Post-Colonial scholarship and illuminates the current situation in Puerto Rico.

Works Cited

Aldarondo, Cecilia, Hofmann Kanna, Ines, Alvarez-Mesa, Pablo, Long, Terra Jean, Negrón, Angélica, Blackscrackle Films, Presenter, Independent Television Service, Production Company, and Good Docs , Distributor. Landfall. 2020.

Duany. (2002). Puerto Rican Nation on the Move. The University of North Carolina Press.

Hinojosa, J. (2018). Two Sides of the Coin of Puerto Rican Migration: Depopulation in Puerto Rico and the Redefinition of the Diaspora. CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, 30(3), 230+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A581024271/AONE?u=marriottlibrary&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=76cdc6fe

Lloréns, & Stanchich, M. (2019). Water is life, but the colony is a necropolis: Environmental terrains of struggle in Puerto Rico. Cultural Dynamics, 31(1-2), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374019826200

Mora, Rodríguez, Havidán, & Dávila, Alberto E. (2021). Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico : disaster, vulnerability, and resiliency.

Santiago, A. (2021, October 13). Inversionismo del Desastre. WAPA.TV. https://wapa.tv/programas/cuartopoder/inversionismo-del-desastre/article_af00caa6-beb0-5d3b-b161-f0bcd9e2dfa9.html

Whiteside. (2019). Foreign in a domestic sense. Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland), 56(1), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018768483

Zorrilla. (2017). The View from Puerto Rico — Hurricane Maria and Its Aftermath. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(19), 1801–1803. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1713196