David Eccles School of Business

3 Art-Secured Lending and Evaluating the Loan-to-Value Ratio in Art and Real Estate Lending Markets

Bennett Blake

Faculty Mentor: Jeffrey Coles (Finance, University of Utah)

A Senior Honors Thesis

Date of Submission: April 21, 2023

Abstract

I analyze the lending terms for loans with art as collateral. The standard loan-to-value (LTV) ratio offered by private banks is 50% of the value of a piece/collection, while for other tangible assets, such as real estate, LTV is often 80%. I use a linear regression model with common U.S. stock indices as my independent variables to compare systemic and idiosyncratic risk for art and real estate. My analysis indicates that differences in these risk characteristics explain in part the substantially lower LTV ratio for art versus real estate. I also examine concerns about market liquidity, ownership, and authenticity of art as they pertain to LTV.

1 – Introduction

Fine art is a complex market that attracts some of the wealthiest individuals in the world. The most coveted painters regularly sell for tens to hundreds of millions of dollars depending on the appetite of a small group of collectors. It is a market that is opaque, loosely regulated, and inaccessible to the average individual. Art also has an increasingly active lending market, where collectors can take out loans with their art collections serving the function of collateral. By this I mean that the art serves as security for the repayment of the loan. This is similar to how one can borrow against their house in promise of repayment.

I compare the art market with the U.S. real estate market under the expectation that risk characteristics of art returns, and how those characteristics differ from those of housing returns, influence the terms of art-secured loans. Additionally, I discuss why private banks, who are creating some of these loans, find value in the market for loans with art as the collateral.

A reason that fine art is an attractive asset to collectors is the fact that art is aesthetically and spiritually valuable. It can often embody the personal values of collectors and represent their own aesthetic sensibilities. Individuals and families end up developing long-lasting relationships with paintings, in which the presence of a piece represents an aspect of their legacy. Aside from the aesthetic dividend art pays (Etro & Stepanova, 2021, p. 108), collectors are drawn to the status of owning museum-quality works of art in their homes since they can show off their collections to their social and professional networks. There is also data to suggest that making fine art a component of one’s portfolio can be valuable in terms of both portfolio diversification (Mei & Moses, 2002, Table 1) and potential appreciation in value of the art. For these and possibly other reasons “Ultra-High Net Worth Individuals” (UHNWI) are interested in art collecting.

Art tends to have a less-active and less-liquid market than more typical securities, such as a debt or equities. To capitalize on the economic value of an artwork, collectors traditionally had to find a private-buyer or auction the work, where values exist only as estimates and sales can take months from start to finish. The low reliability of pre-auction estimates (Yu & Gastwirth, 2010, p. 850) and the time to facilitate sales make it challenging for collectors to use their art to cover short-term cash needs. Art lending, which was first formally offered as a service by Citigroup’s Private Bank in 1979 (Neuhaus, 2015, pp. 146-147), has been rapidly expanding to allow collectors to use their art as a security for a loan.

An asset-secured loan is a type of loan where the guarantee of repayment is backed by another asset. Loans backed by real estate, such as mortgages, are asset-secured loans. In like manner, art is a tangible object with value as collateral. The lending party, typically a bank, will lend at a fraction of the value of the collateral called the loan-to-value ratio (LTV). This ratio is important because it represents the risk banks are willing take in the event the loan isn’t repaid. Failure of repayment, also known as a default, allows the lending party to repossess the underlying security of an asset-secured loan. The LTV is then effectively how much the lending party paid in order to acquire the collateral. The LTV ratio for fine art, across the industry, tends not to exceed 50% (Medelyan, 2014, p. 652). Alternatively, real estate typically has a LTV of 80% (Lack, 2016, p. 47), which is higher than fine art.

Many UHNWIs have used their art collections to finance art-secured loans (Medelyan, 2014, pp. 651-653). According to John Arena (2022), director of Deutsche Bank’s art lending team, the art-secured lending market was expected to reach $31.3 billion in 2022, an 11% growth rate from the previous year. This, however, represents a fraction of the total value within the art market. According to Deloitte, the total value of UHNWI art and collectibles was estimated to be $1.49 trillion in 2020 (Arena, 2022). Art and other collectibles on average comprise 9% of high-net worth individuals’ portfolios (Li et al., 2022, p. 2). Currently, there still appears to be a large addressable market. The double-digit growth rates of recent years could be potentially sustainable for the foreseeable future.

Using data that tracks the returns of art and real estate markets, I examine the extent to which the risk characteristics between these two asset classes offers explanatory power for the differences between LTV ratios. With this data, I conducted a regression analysis using common U.S. stock indices as the independent variable. The regression models estimate both the systemic and idiosyncratic risk of market returns for real estate and art. Differences in these components of risk suggest why LTV ratios are different for these two asset classes and why banks are likely to provide more value on a home-equity loan versus a loan against a fine art collection. I find that art tends to be less sensitive to market returns than real estate (meaning that art has lower systemic risk) and that real estate tends to have slightly higher idiosyncratic risk. The latter is due to greater volatility in past real estate returns and lower exposure to general economic conditions. The statistical differences in these risk components supports the argument that LTV ratios of 50% are justified despite surface level similarities between these two asset classes.

2 –Lending Collateral: Real Estate as an Analogy for Art

To understand why art-secured loans have a lower LTV ratio relative to other real assets, I choose real estate as an analogy. Real estate provides a strong point of comparison to fine art for several reasons. Not only do both have active lending markets, but they are also tangible and provide some kind of service flow. For instance, real estate can be lived in or rented to others and art provides the collector with status and aesthetic pleasure. They also share the characteristic that the underlying asset is truly unique. Art, even produced by the same artist, can differ significantly in value based on size, condition, and historical importance (Sotheby’s). In like manner, even two houses that are structurally identical will be on different plots of land, have different maintenance concerns, and consequently will be valued differently. Additionally, fine art and real estate both share liquidity concerns where the sale of the asset will typically take months to find the right buyer and include a seller’s fees.

Nevertheless, there are several key areas where these assets differ, which could potentially create differences in their respective lending markets. Homeowners are present in many economic demographics, whereas the art that qualifies for art-lending is mostly owned by the highest echelon of wealthy individuals, the UHWNIs. The service flow that real estate generates provides a more tangible source of value since it tends to be easier to quantify cashflows from rent than the value of the consumption stream from proximity to fine art. There are also many risks that are unique to art, such as higher risks of art going unsold at auction, authenticity of individual paintings, and lack of a transparent and fully accurate system to record titles of ownership. These risks would be considered idiosyncratic risks of art since they are particular to art as an asset class.

The similarities and differences between real estate and art provide me with a starting point for attempting to explain the LTV discrepancy between these assets, 50% in art versus 80% in real estate. Since these two assets share a few core similarities, the discrepancy in LTV ratios might be explained by art having risk characteristics that differ from those of real estate. A bank can hedge market risk but, unlike real estate, the art market is relatively thin and the idiosyncratic risk of the value of art as collateral is not easily diversified. The difference in LTV ratios potentially would be explained by the idiosyncratic risk of art being greater than that of real estate. Nevertheless, I tested both systemic and idiosyncratic risk to explore whether we might gain further explanatory power into why banks aren’t providing the same loan value for art as they do with real estate.

3– Landscape of the Art Lending Market

3.1 Role of Private Banks

There are several institutions that are willing to lend against art as collateral, such as luxury pawnshops, auction houses, and private banks (Neuhaus, 2015, pp. 146-149). Each serves a specific niche in the lending market, but private banks are particularly interesting because it is not directly obvious how a relatively small business within private wealth management would be capable of art lending as compared to a large investment bank. Such banks have traditionally supplied capital via more typical securities. On the other hand, many private banks rely on third parties to engage in art-lending, rarely repossess artwork, and do not charge high enough interest rates to generate significant revenue. These are characteristics of services that tend to be atypical for investment banks. These few considerations pose the question of why this service exists in its current form.

There are two primary factors that help explain why private banks are willing to take a risk on fine art. First, is that this service cross-fertilizes other businesses within the private banks by creating a strong relationship with clients that might lead to business elsewhere within the bank. Since the trades of an individual client are confidential, it is challenging to estimate the value that this service provides for a bank. Nevertheless, a 2018 survey from Deloitte and ArtTactic Ltd states that 40% of private banks are looking to make art-lending a strategic focus in the coming year (“Cash in on your Picasso”, 2019). This is consistent with the strong growth this service has seen in recent years, and why it is projected to expand further. Second, a lower LTV for fine art compared with other assets, such as real estate, might suggest that the private bank is taking on less risk. But if art is riskier collateral, banks will loan less relative to the underlying value of the collateral until the risk of such collateral is tolerable to the bank. A lower LTV for fine art suggests that private banks see art as a riskier asset than real estate. On the other hand, inconsistent with the assertion that art is riskier, literature suggests that art market index returns are steadily 1% above inflation (Zhukova et al., 2020, p. 9). The counterargument is that perhaps such art-market indices do not fully capture the risks associated with liquidity, authenticity, and ownership.

3.2 Loan Terms

Art-secured loans provided by the private banks are typically structured as a revolving line of credit (Blackman, 2015), which is a form of debt that allows those who are receiving the loan to draw upon the credit as required. There is a limit placed on the credit based on the value of the collateral relative to the LTV. One of the benefits of a revolving line of credit is that it allows for more flexibility since withdrawals and payments can be made at any point within the maturity of the loan. Maturities are generally around two-years, and it is uncommon for them to be longer than five years (Medelyan, 2014, p. 652). The most similar loan for real estate is a second-lien mortgage, which is a more junior loan secured by the same house as a more senior facility. These loans, typically referred to as home-equity line of credits (HELOC) can be structured as a revolving line of credit or a term loan.

Private banks also have requirements for the art they will accept as collateral. First, the art must be appraised annually and authenticated by a third party (Ray, 2015, p.18), typically an independent authenticator. For the bank to establish a security interest, a lien, on the collateral, due diligence is required by Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (Medelyan, 2014, pp. 645-646). Single works of art are typically insufficient to comprise collateral. Instead, usually a collection of works would be collateralized. JPMorgan Chase’s private bank requires that the collection be diversified, a minimum of five pieces be put up as a security interest, and the value of each piece must exceed at least $750,000 (“Case in point”, 2016). Other banks require that the art in question must be valued at least $10m (Blackman, 2015). Having at least five pieces that meet these conditions implies that, to qualify for a loan, the client of the bank likely has a fairly substantial art collection already. This parallels how the bank will typically lend against a portfolio of stocks, as opposed to a single stock, in order to reduce idiosyncratic risk. Similarly, in the case of art, this might be strategy to reduce the risk around particular pieces in the collection which might produce competing ownership or authenticity claims in the unforeseeable future. To further mitigate risk, private bank’s structure these loans as recourse loans (Neuhaus, 2015, p. 146), which allows them to repossess other assets in their client’s portfolio in the rare case of a default. Since wealth managers have unique insight into the myriad of different investments that their client owns, finding alternative sources to repay the defaulted debt would likely not be a challenging barrier, although it could potentially damage a client relationship.

Interest rates on art-secured loans tend to be low ranging from 0.71% to 3.25%, approximately the range of 30-year U.S. treasury notes, which is considered a relatively risk-free asset (St. Louis Federal Reserve, 2023). On the contrary, 30-year mortgage rates on real estate have typically been between 3% to 6% in the last two decades (Freddie Mac, 2023). In 2015, for instance, gaming magnate Steve Wynn borrowed against his art collection at an interest rate of only 1% (“Case in point”, 2016). Offering low rates suggests that private banks, to some extent, view art lending primarily as a relationship-building business.

Numerous sources have found that a maximum 50% Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio is standard among private banks. According to Citigroup’s private bank head of art advisory Suzanne Gyorgy, a LTV of 50% with a minimum of $10m tends to be the standard for their loans against art (Blackman, 2015). This sentiment was echoed by John Arena (2022), head of Deutsche Bank’s private bank art advisory team. Simply put, that means a single painting valued at $10m would be able to produce a line of credit with a maximum of $5m. Real estate, however, most commonly has a LTV ratio of 80%, which implies that a home worth $10m would be able to secure a loan of $8m.

3.3 Advantages of Art Lending

What appears to be the primary advantage of art loans from the bank’s perspective is the ability to distinguish themselves and drive deal activity through other businesses. The teams that facilitate these art loans typically fall under the umbrella of an art advisory team within private wealth management services. Due to the unique nature of alternative investments, such as fine art, having an experienced advisory team allows the bank to appeal to clients with substantial collections of art in their portfolios, with the expectation that these clients will take advantage of other wealth management services the bank has to offer. Additionally, investment banks look to their private wealth management clients to place securities or secure funding for upcoming deals (Weinberg, 2017). Offering art lending, especially at relatively lower interest rates, keeps their clients happy and thus generates more business for the banks.

Another advantage for the private banks comes from the fact that foreclosure is uncommon, and the banks do not want to put their clients in a position where they take on more debt than they could pay back. John Arena (2022) of Deutsche Bank claims he has never seen a foreclosure happen, even with 27 years of being in the business. Considering that many collectors have art that has been passed down, or they themselves have felt an aesthetic connection with the work they purchased, repossessing a piece of art would likely significantly damage a client relationship. Banks are able to mitigate default risk through relatively low LTV ratios, in addition to the fact that they have extended insight into their client’s portfolio. Arena also states that while a collector’s main hesitation about using their art as collateral is the fact that they might lose it, the bank will rarely extend a loan to somebody who they believe cannot pay back the loan through some other source on their balance sheet.

From the perspective of collectors, there are several advantages for securing a loan with their art. According to the Deloitte/ArtTactic survey of collectors, over 50% of collectors said they would be interested in the service with 53% saying they would use the loan to acquire more art, 38% saying they would use the money to finance existing business activities, and 9% saying they would use it to refinance prior loans, possibly ones with higher interest rates than an art-secured loan (Blackman, 2015). Although the majority of collectors interested in this service are looking to expand their art collections, there are many who intend to use this new source of capital to finance other areas of their portfolio, besides their collection. Another advantage of art lending, particularly in the United States and Canada, is the ability for collectors to keep their art in their homes (Neuhaus, 2015, p. 147). Considering the service flow of art, this means that collectors can continue to enjoy the aesthetic and social satisfaction that fine art provides. Additionally, private banks benefit from this rule since it implies that they will not be burdened with finding storage or covering insurance for the collateral, just conducting the due diligence required to confirm that storage and insurance exist.

The art lending business appears to be propelled by the belief that if you keep your clients happy by offering a unique service, then they will be more likely to do business with you elsewhere. Transitioning to a discussion of the quantifiable risks that banks take by extending loans on art, this belief supports why banks are willing to take on a seemingly risky venture, while charging low interest rates, which is typically inversely related to risk. Not every client of a private bank will have an art collection and even if they do, they still must qualify for the collateral restrictions that banks put in place. That implies that it is likely that this service only comprises a small fraction of the investment bank’s total businesses.

4 – Hypothesis

To test why an art-secured loan has a lower LTV ratio than real estate, I hypothesize that this was due to differences in risk characteristics between these two asset classes. Specifically, I suppose that the value of art is less sensitive to external market forces than real estate, a greater proportion of risk can be hedged with real estate than with art, and that there is greater noise (unhedgeable risk) for art than real estate. Such suggests the hypothesis that a reason that LTV ratios are lower for art than real estate is the fact that the risk characteristics of art are not only more difficult to hedge, but also more difficult to forecast.

The null hypothesis I test is that art is not less sensitive to external market forces than real estate, art has a greater proportion of risk that can be hedged than real estate, and that there is not greater noise within the models for art. If I accept the null hypothesis, I reject that risk characteristics are partially responsible for the discrepancies between the LTV ratios. This may imply that idiosyncratic forces such as liquidity, authenticity, and lack of ownership transparency are likely the primary drivers behind the discrepancies in LTV ratios.

Support for the hypothesis does not reject that idiosyncratic factors do not contribute to lower LTV ratios for art-secured loans, but instead offers further explanatory power that differences in relative LTV ratios may also be driven by quantifiable market forces.

5 – Data

5. 1 Sources

I conducted my analysis using three popular U.S. stock indices as my independent variables. The indices I employ are generally accepted as approximately representative of U.S. stock market performance. The Russell 3000 represents the broadest view of the performance of U.S. publicly traded equities since it tracks the returns of the top 3000 U.S. publicly traded companies, ranked by market capitalization, essentially the capital size of the underlying company. The S&P500 gives insight into the top 500 U.S. publicly traded companies ranked also by market capitalization but adjusted to consider the volume of shares traded publicly. The final index is the NASDAQ which is calculated by all the equities which are traded on the NASDAQ stock exchange.

For my art dependent variable, I primarily relied on the art indices provided by Art Market Research (AMR), which is considered the industry standard for tracking the performance of a variety of collectible markets including art, wine, cars, and watches. I have also included data from the ArtPrice indices, which use a similar methodology as AMR, but produce somewhat different results for analogous categories. In regression models estimated using the ArtPrice indices, the coefficients on stock market returns were not statistically significant. Accordingly, for the purposes of my analysis I use the AMR indices. The AMR index methodology applies a repeat-sales model from data taken from analysts at AMR, as well as from data independently provided by auctioneers. I choose two of their indices Art 100 and Contemporary Art 100 which compile auction results from the top 100 trading global and contemporary artists, respectively. Considering the $750,000 requirement that some banks place on art to qualify as collateral, this would likely be reflect the value of work of those 100 artists. Nonetheless, there is plenty of art that is valued above $750,000 that is not the work of the 100 artists. The ArtPrice indices I utilize are from ArtPrice Base 100, which also segments by the top 100 global and contemporary artists and also includes data given a distinct medium (painting, sculpture, drawing, etc.). I also include the ArtPrice Global index in all of my tables, as a means for comparison, although I base my conclusions on the AMR data.

For my real estate dependent variables, I choose the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts Residential (NAREIT) and the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index (Case-Shiller). The NAREIT is calculated via the net operating income of the underlying homes, which provides insight into the performance of the residential real estate market in the U.S. Case-Shiller uses a repeat-sales model to track systematic changes in home prices. Although Case-Shiller’s methodology is most similar to the AMR, it had no significance to any of three U.S. equities indices, which appears to run counter to the conventional expectation that the performance of real estate at least somewhat reflects the performance of the stock market. For this reason, in addition to the fact that the NAREIT was always statistically significant with the three stock indices, I choose to base my results on the NAREIT. Since any of the conclusions using the Case-Shiller index could also be explained by randomness in the model, I believe that NAREIT was a better source for my analysis.

5.2 Summary Statistics

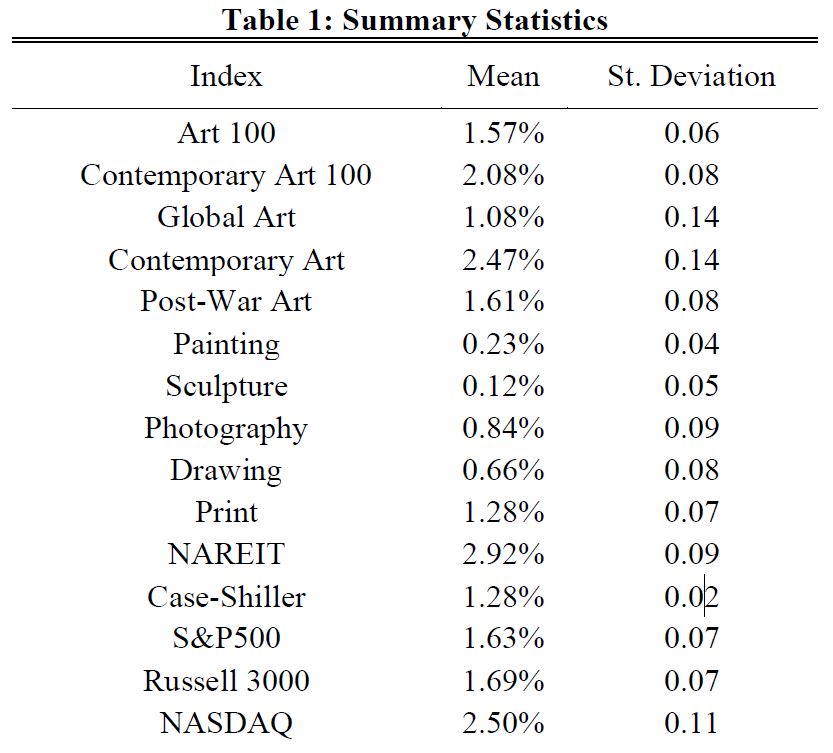

Relevant to my analysis of the risk characteristics of fine art and real estate is the mean and standard deviation of the returns for their indices. Table 1 shows that the average returns I found for the global and contemporary art indices appear consistent with other research (Zhukova et al., 2020, p. 9) that demonstrate that annual art returns average about 1%, with contemporary markets being slightly higher. The NAREIT returns an average of about 2.9%, which is higher than all of the art indices.

The standard deviation, or volatility, of the AMR indices is lower than NAREIT. On the other hand, the volatility of the ArtPrice indices is greater than that of NAREIT. Relying on the AMR data, it is then even more confounding why an asset that is less volatile than real estate, is given a lower LTV ratio. A possible explanation for this is that private banks are not lending against an index of art as a security, but rather individual paintings which may not reflect the performance of the index. Depending on the group of artists who created those pieces, there could be dramatically different risk profiles, even more nuanced than individual categories such as time-period or medium. While it is possible to analyze the returns of an individual’s artworks, the infrequency on which a particular piece is traded means that very few data points will typically exist for a given artwork. On the other hand, investment banks have security vehicles such as Collateralized Debt Obligations which are designed to reduce the risk of default on any particular piece of real estate. This is likely one of the many complications private banks have when deciding on an appropriate risk tolerance for art.

6 – Methods

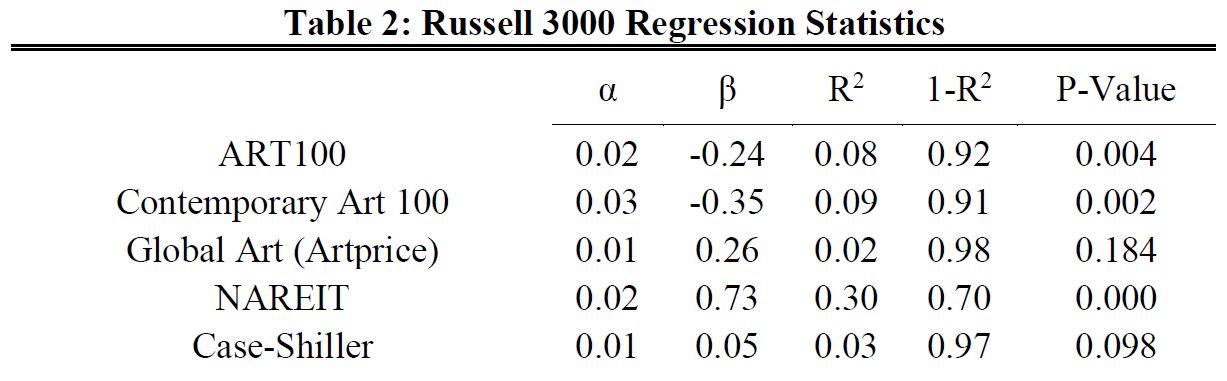

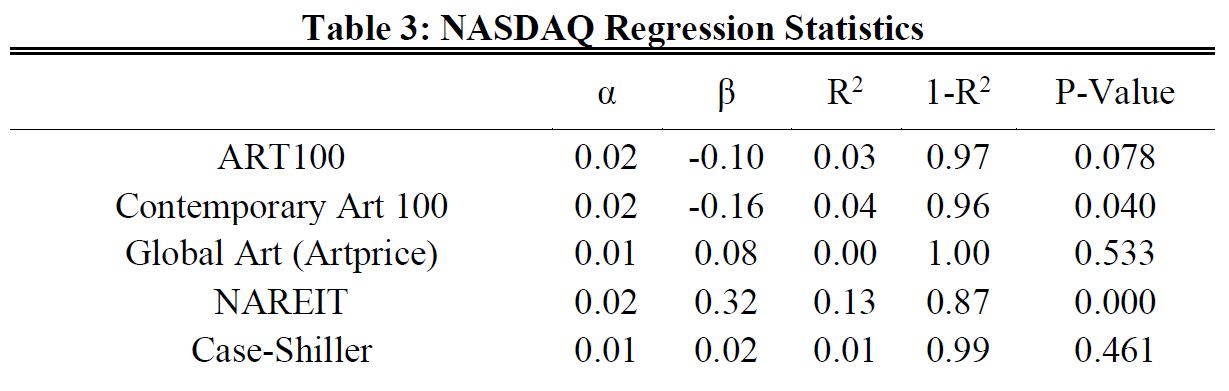

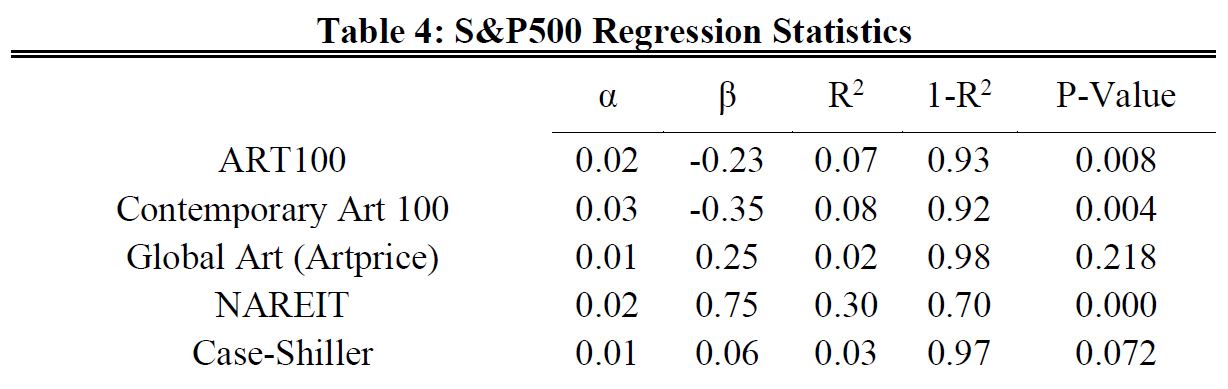

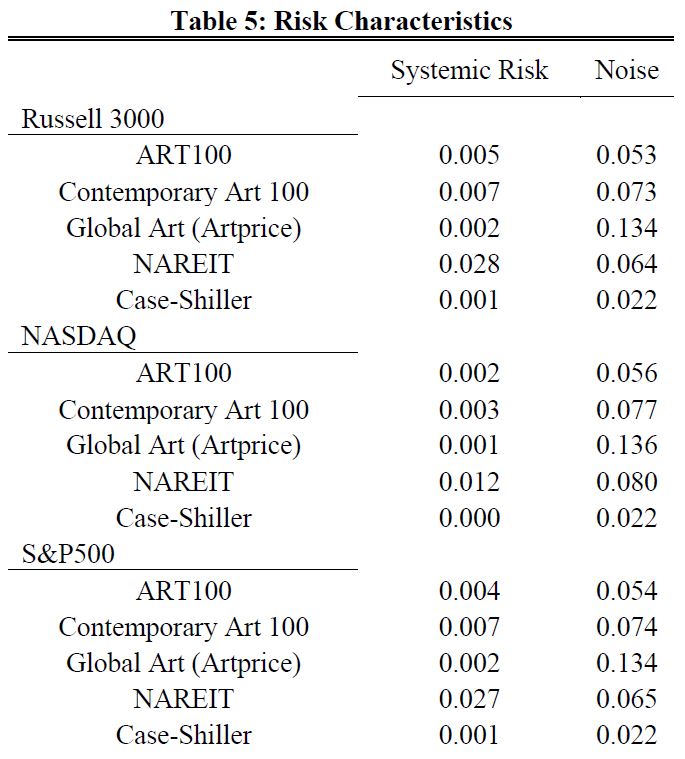

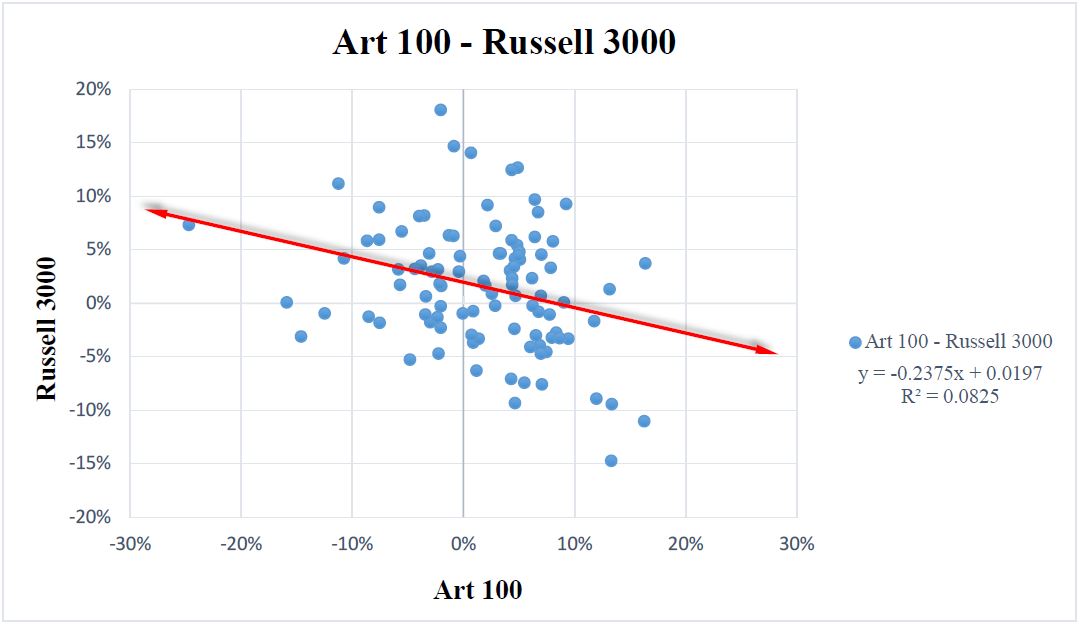

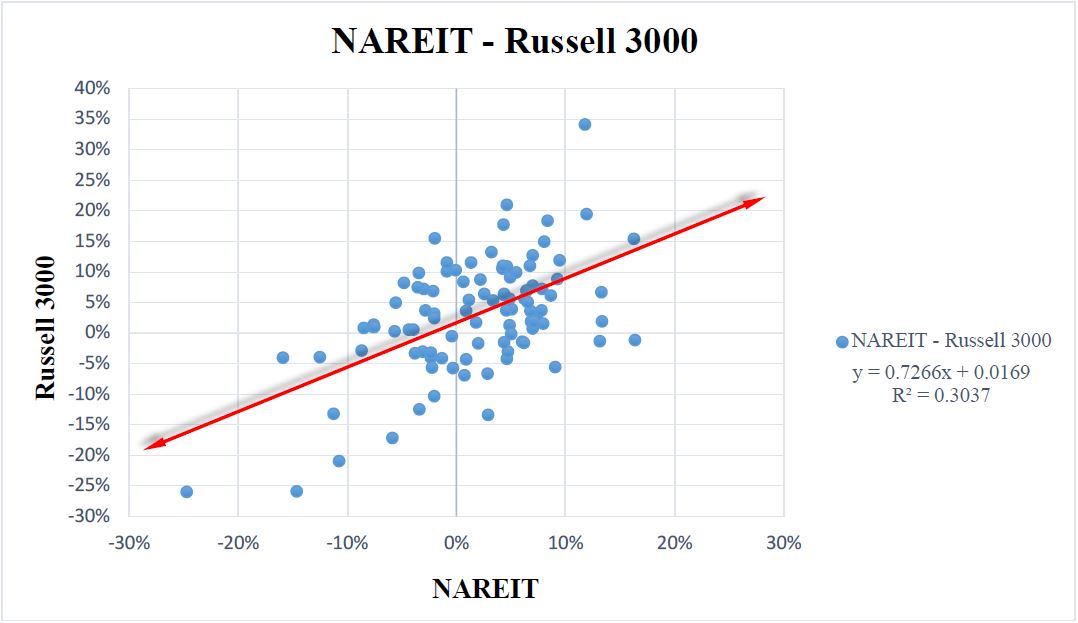

For my analysis of the risk characteristics of art versus real estate, I estimate a linear-regression model using quarterly return data over the time-period of January 1998 – December 2022. This provides 100 observations and 99 return observations that span over two decades. These decades include both strong stock market growth as well as the major financial crisis of 2008. This allows the regression to test the response of art and real estate to both positive and negative market pressure. I chose a regression model to analyze the discrepancies around the LTV of art versus real estate because it yields estimates of the most fundamental risk statistics of art, including the sensitivity of the returns on the relevant asset (art or real estate) to stock market returns (β), the proportion of variation in art returns explained by the regression model (R2), and the proportion of variation unexplained by the model (1-R2). Table 1 includes the average returns and standard deviation of every index that I analyzed over the course of my research. In Tables 2-4 I include relevant regression statistics of the indices I chose to focus my analysis on relative to a single independent variable. In Table 5, I calculate the systematic risk and noise of the dependent variable for each independent variable. The calculation in Table 5 uses the standard deviation along with the percentage of variance within the regression model to produce calculations for systemic risk and noise which represent the level of hedgeable risk of the dependent variable (σ*R2), as well as the level of unhedgeable risk of the dependent variable (σ*(1-R2)). Charts 1 and 2 are a representation of the regression of Art 100 and NAREIT against the Russell 3000 as the independent variable. This was included to provide a visual summary of the differences between the relationship of art and real estate to the stock market over the last 100 quarters.

7 – Results

7.1 Sensitivity and Systemic Risk

This section outlines the results included in Tables 2-5. I first explain the results of the sensitivity (β) comparison between fine art and real estate and then compare my results for the level of systematic risk for the two assets.

The β of Art 100 (Table 2: β = -.24) tends to be slightly negatively sensitive to the Russell 3000, S&P500, and has almost no connection to the NASDAQ index. In Chart 1, this appears to be primarily due to a few outliers in the third quadrant. This is consistent with other researchers (Mei & Moses, 2002, Table 1) in its application to the present day that art does provide a diversification benefit in a well-diversified portfolio. The sensitivity of Contemporary Art 100 (Table 2: β = -.35) is similar, although its negative sensitivity is slightly amplified. The NAREIT (Table 2: β = .73), however, has strong positive sensitivity to the movements of the independent variables. This appears to suggest that housing prices are impacted by or associated with the performance of the stock market. This is borne out in my data. The results are consistent with the first part of my hypothesis, specifically that art has less sensitivity to the stock market than real estate.

This provides some evidence that there may be systemic risk characteristics of art that can explain why art-secured loans typically carry a lower LTV ratio than the loans secured via real estate. All of the regressions that I have included in my research demonstrate that the sensitivity of the dependent to the independent variable (β) tends to be higher for real estate than it is for art. It might be the case that since art does not appear to be as sensitive to the market as real estate, investment banks do not see their macro-economic views of markets to be particularly useful in this business. Since it appears that their data is not a strategic advantage in forecasting the art market, let alone individual pieces, it is expected that they would hesitate in providing more loan to value than they would with real estate. Although art has been shown to be a relatively stable, low-returning asset, which is consistent with my analysis, it is not reactive to the stock market, which might make it challenging to find ways to reduce risk.

Art has significantly less hedgeable risk than real estate by a factor of about six for the Russell 3000 in Table 5 (Art100 = .005 & NAREIT = .028). In Table 2, the R2 statistic for the Art 100 (.08) is about three times smaller than the NAREIT (.3). This discrepancy becomes amplified to six when multiplying by the variance of returns since the standard deviation of the NAREIT (σ = .092) is almost double that of the Art 100 (σ =.058). The measurement of systemic risk for art (Art100 = .005, Contemporary Art 100 = .007) strongly implies that almost none of the risk of art can be hedged using stock market indices. The measurement of systemic risk for real estate (NAREIT = .028), albeit small, represents a much larger proportion of risk that can be hedged. Systemic risk is relevant to the LTV ratio of these assets since it is the amount of risk that the banks can diversify away when creating loans. This brings me to the second part of my hypothesis, which is that a greater proportion of risk can be hedged with real estate than with art. The availability of derivative securities to reduce systemic risk justifies why banks are willing to lend at LTV ratios of 30% more for real estate than they are with art.

The result for systemic risk demonstrates that real estate has significantly more hedgeable risk than art. Hedgeable risk determines the proportion of the underlying asset’s risk that can be reduced by the bank, thus banks would be more likely to provide a lower LTV for an asset that they cannot hedge their risk for. All three stock index tables support the hypothesis that the reason banks are willing to provide more value for the collateral of real estate instead of art is because they are better able to reduce the risk of real estate, by a factor of about 6. The risk of not being able to hedge art is partially offset by the consideration that private banks are taking a macro-view of their client’s portfolio when deciding to extend an art-secured loan. Risk is also partially reduced by the collateral requirement of a minimum of five pieces. Finally, since banks are only lending 50% of the value of the artwork, they can reduce their overall exposure and avoid having to deal with the complications of hedging that this analysis demonstrates.

7.2 Idiosyncratic Risk

Included in my analysis of the risk characteristics of fine art versus real estate are their statistics for noise, also considered the measurement of idiosyncratic risk. Table 5 demonstrates that art has a slightly smaller statistic for noise than the NAREIT (Art 100 = .053, NAREIT = .064). There is still some support for the third part of my hypothesis, however, considering that Art 100 has a greater 1- R2 than the NAREIT (Table 2: Art 100 = .92, NAREIT = .7). This observation is grounded by the comparison of Chart 1 (Art 100 – Russell 3000) and Chart 2 (NAREIT – Russell 3000) since the points on Chart 2 follow a clear upward trend versus the seemingly random distribution of data points in Chart 1. The result that art has a slightly smaller statistic for noise was in part caused by the standard deviation of art being smaller than real estate (Art 100 σ =.058, NAREIT σ = .092). In summary, although the returns on art tend to be less volatile than real estate, there is significantly more unexplained variance when regressing art and real estate against a major U.S. stock index. This is consistent with the third component of my hypothesis, despite the fact that there is slightly more unhedgeable risk for real estate. This is due to the returns on real estate being more volatile, rather than because my regression model was better able to explain the variance. When controlling for standard deviation, the movements of these popular stock indices do not explain the distribution of points for art as much as they do for real estate.

Considering that the function of a bank is generally to avoid positions where risk is poorly understood and difficult to hedge, it follows that they would use LTV ratios as a lever to reduce their overall risk exposure to art. While they could charge higher interest rates to reflect the greater risk of art, this runs counter to the philosophy of this service being one of relationship-building. Instead, lowering LTV ratios allows borrowers to receive substantial loans on their art in addition to improving the ability of those clients to pay back the principal without creating unnecessary risk for the bank.

The larger proportion of unexplained variance in the regressions using art indices might be explained by three primary risk factors that are unique to art as an asset class: liquidity, authenticity, and ownership. Traditionally, banks are not in the business of facilitating art-related transactions, providing authenticity opinions, and tracking ownership of art. These roles are typically specialized third-party services that require expertise. Alone, these factors can significantly impact the value of a given artwork, and thus deserve their consideration in attempting to explain why art has more unexplained variance than real estate.

7.2.1 Liquidity

Liquidity represents how fast an artwork can be sold for acquisition or appraised value. The sale of an artwork can often take months, insofar as the right type of auction may not be immediately available (Li et al., 2022, p. 2). Every piece of art has a unique value, even those that are essentially the same artwork such as a print. Coupled with the fact that the market for art is so thin, with relatively few buyers and sellers, as compared to real estate, what an estimator sets for the value of art may not accurately forecast the sale price (Yu & Gastwirth, 2010, p. 850). An auction sale for an artwork will typically have a reserve price, which must be met or exceeded for the transaction to be facilitated. In many cases that reserve price is not met or no bids are made, which leads to around 40% of auctioned items going unsold (Bruno et al., 2018, p. 833-834). An item failing to achieve a sale at auction indicates that the demand for that piece was not as strong as it was originally thought to be. This event often leads to the artwork being reappraised at a consistently lower value (Ashenfelter & Graddy, 2011, Figure 2) or being shelved for a future auction date when market demand is believed to be significantly different.

7.2.2 Authenticity

The authenticity risk of art also presents challenges that can significantly affect the value of an individual artwork. Authenticity refers to whether the artwork can be attributed to the artist whose name is associated with the work. Art from established, blue-chip, artists is a prime victim of counterfeiting. Successful forgeries can be worth millions of dollars. Advances in machine learning for the application of art authenticity opinions likely would improve the process of conclusively determining authenticity (Łydżba-Kopczyńska & Szwabiński, 2022, pp. 17-18) yet it is still estimated that 40-50% of contemporary art that is circulating in the market is inauthentic (Li et al., 2022, p. 2), although verifying this estimation is challenging. Due to the legal liability of issuing a formal opinion on whether a piece of art is authentic, many authentication experts are hesitant about giving conclusive opinions. Even the slightest expression of doubt can significantly devalue a work. Additionally, there are no legal qualifications around being considered an art expert, and due to the opaque nature of the art market, it is challenging to establish whether an authentication expert has a financial interest in the authenticity of a particular artwork (Bandle, 2015, p. 382). These factors represent a relevant risk for banks, as authenticity is one of the main drivers of value for a blue-chip artwork. Paintings that are found inauthentic would be worth only a fraction of what the value of an authentic painting would be. Additionally, there is a contagion effect on the value of any painting of an artist whose work is forged as soon as the media reports of even rumors of a forgery on another work (Li et al., 2022, p. 13). By requiring multiple pieces for a loan to be established, banks can mitigate some of this risk, but it is another reason why they prefer loans to be paid back instead of repossessing the collateral.

7.2.3 Ownership

Private banks must navigate ownership risk when dealing with fine art. In the U.S. real estate market, the vast majority of all transactions are recorded in the Public Recorder of Deeds office (Pearson, 2015, paras. 12-13). The information on the Public Recorder of Deeds is public, so it is not challenging to determine whether an individual actually has a valid title of ownership in the case of real estate. Art, on the other hand, has no such public ownership record, most of the market is private, and for the auction houses, which tends to be the most public market for art, very little information is available about auctioned works. Although the blockchain has offered new opportunities for authenticating ownership digitally (Fairfield, 2022) and companies such as Verisart have been issuing digital certificates of authenticity, there is still no widely accepted public practice resembling the Public Recorder of Deeds. Traditionally, the closest analog in the art market for recording deeds are catalogue raisonnés, but they can be inaccurate and fragmentary, sometimes even including forged works. The existence of ownership records such as certification and reference in art literature, however, does have a positive effect on price (Li et al., 2022, p. 23). The absence of accurate ownership records implies that it is possible for a private bank to establish a security interest in an artwork that their client doesn’t legally own. Since the client never possessed legal ownership, a repossession is not able to produce a superior title and the bank could essentially lose ownership of the collateral. Although it is possible to reduce this risk through ownership insurance, it is still a unique risk of art that banks must consider when offering art-secured loans.

8 – Additional Considerations

8.1 Review of Analysis

This analysis provides a starting point for attempting to explain the discrepancies in LTV ratios using data from art and real estate indices. In this section I will outline some of the strengths and weaknesses of my approach, as well as some areas for further research on this topic.

An advantage of using a simple regression model to compare the risk characteristics of art and real estate is that it allowed me to compare statistics that tend to be more general in conclusion than more specific data analysis techniques. In the absence of information about the actual credit-scoring model of private banks for art-secured lending, these broader statistics allowed me to formulate a hypothesis that might explain the discrepancies around LTV ratios for art and real estate secured loans. The sources I used were chosen because they are also some of the broadest indicators of performance for particular asset classes.

Due to the simplicity of the model, there are also some weaknesses that could be accounted for by including other data analysis methods or other sources. For instance, in every regression I ran I was comparing two variables. More specific research into the risk characteristics of the art market by segment might employ a multiple linear regression model to account more accurately for how different sectors of the art market are responding to the stock market. Additionally, the loans available for residential real estate purchased by UHNWI might be significantly different than a typical 30-year mortgage, which was the LTV ratio I compared. I also used mortgage terms that are provided by commercial banks who could potentially have a different risk tolerance for lending than private banks which are selling the art-secured loans. Nevertheless, I did not find any evidence that a LTV ratio of 80% would not apply to a private bank loan which allowed me to find it acceptable for the purpose of this research.

There were also several unresolved concerns when comparing the data between similar indices. The data from AMR and ArtPrice, which are two separate data companies tracking the same market, produce different results when regressed against the same independent variable. For instance, the β for Art 100 (AMR) in Table 2 is -.24 versus Global Art (ArtPrice) .26, almost opposites of each other. A possible explanation in the discrepancies between AMR and ArtPrice is that auction house data tends to be proprietary and public announcements of sales, which could have found their way into either of these indices, are not typically adjusted to consider variables within the final sale price such as buyer/seller fees. The regression statistics for Case-Shiller were also troubling since it had almost no sensitivity to the market, which goes against the generally accepted belief that real estate prices are at least somewhat related to stock market performance. Also, the NAREIT and the Case-Shiller index had almost no sensitivity to each other. This is problematic because they are tracking the same underlying asset, despite using two different methodologies. An additional investigation into the discrepancies between these data sources, for both art and real estate, might be required to measure the risk characteristics more accurately.

For further research, I believe that many of the collateral requirements for art-secured loans would be worthwhile to explore. For instance, whether there is selection bias in the artwork that is collateralized, whether there are restrictions on the medium of the collateral, and whether artwork from certain artists is deemed too risky to be collateralized. This research also didn’t consider the role of auction houses and luxury pawnshops, two other art-secured loan providers that serve a different customer demand than private banks.

8.2 Further Research

There is much research to be continued on this topic, and it is unclear how the value of art will continue to evolve in response to the growth of art-secured lending markets. Due to the confidentiality around what art is really being held as collateral, it is unclear how much status an artist must have for their artwork to be eligible for a loan. While there are industry standards, such as the LTV ratio of 50%, there are a lot of unknowns to the public about what makes a particular private bank’s art loan unique. Furthermore, there is evidence of institutions using art loans to tap into their liquidity during difficult times (Medelyan, 2014, pp. 651-652). There is strong possibility that museums and other arts institutions will look at lending against their art, possibly the art that is storage as well, to cover costs, instead of laying off employees or reducing spending elsewhere. This could dramatically alter the way that these institutions think about their balance sheet and could influence the way that they choose to serve the public. This would require reconciling differences across various art indices in addition to finding real estate indices that more accurately represent the holdings of UHNWI’s.

9 – Conclusion

Despite the risks of art as a collateral, private banks are still insistent on developing this service for their clients. Banks minimize risk by choosing to lend at relatively lower LTV ratios and by doing their due diligence on their client’s portfolios to ensure they have the capital to repay the loans. The risk-return characteristics of art compared with real estate justify lower LTV ratios. By comparing the performance of art and real estate indices with the performance of the stock market over the last 100 quarters, real estate has significantly higher sensitivity to performance in the stock market. Additionally, real estate has more hedgeable risk than art, allowing banks to reduce their overall exposure to real estate as an asset. While the data analysis demonstrated that real estate does have more noise than the art indices, I have determined that this is being driven by past volatility of real estate over art, not by the models having more explanatory power on the variance of real estate. These findings demonstrate that real estate is better understood by the market than art. Accordingly, private banks would be willing to take a bigger risk by providing higher LTV ratios with real estate than art.

The primary idiosyncratic risks of art, which are liquidity, authenticity, and ownership, might explain the greater unexplained variance in the regressions ran against art. All of these significantly affect not only the value of art, but also the potential complications around trying to turn art into cash. The lengthy time periods to sell art would mean that banks would be holding art on their balance sheet, without the guarantee that they will be able to get the 50% of the appraised value that they lent. Since authenticity is one of the primary drivers of a blue-chip artwork’s value, a work of art even rumored to be inauthentic could significantly impact the value of the collateral. Telling a forgery from an authentic work is a complicated and expensive task, despite not getting a guarantee that the work of art is authentic. In the case of a piece of art being improperly owned, banks run the risk of losing the painting in a costly legal battle. Even if there are no competing ownership claims at the time of creating the loan, there is no guarantee that during the life of the loan claims won’t be made. These idiosyncratic factors are other risks that banks must consider when expanding their service for loans against art.

Based on the available research, it appears that a private bank’s goal in making art loans is not that their clients will default, and they will be able to repossess the underlying collateral. Additionally, it appears that banks are not using interest rates to generate additional revenue. Investment banks are not in the business of trading art, although their executives may be, and repossession or high interest rates would go against the central philosophy of this service, to improve client experience. Repossession for private banks is extremely rare, almost unheard of, and private banks minimize this risk by ensuring that clients have liquidity in other areas of their portfolio to pay back the loan in the event of default. Additionally, due to the myriad of risks explained above, having art on the balance sheet further complicates risk management for investment banks. Lending against art as collateral is something that can be analyzed due to similar asset characteristics with real estate, but it is unlikely that banks will look at this service as a strategy to improve their revenues directly. Instead, private wealth managers will continue to advertise this service to their UHNWI clients with substantial art portfolios to encourage them to use the private bank for all their financial management needs and indirectly create value in other divisions of the investment bank.

Tables

Table 1: Summary Statistics

Art100 is an Art Market Research index of the top 100 global artists ranked by annual sales. Contemporary Art 100 is an Art Market Research index of the top 100 contemporary artists ranked by annual sales. Global Art is an ArtPrice index of the top 100 global artists ranked by annual sales. Contemporary Art is an ArtPrice index of the top 100 contemporary artists ranked by annual sales. Post-War Art is an is an ArtPrice index of the top 100 post-war artists ranked by annual sales. Painting to Print are ArtPrice indices of the top 100 artists of a particular medium ranked by annual sales. NAREIT (National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts Residential) is an index of the net operating income of residential real estate in the U.S. Case-Shiller (S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price) is an index of home-prices using a repeat-sales model. S&P500 is an index of the top 500 U.S. publicly traded companies. Russell 3000 is an index of the top 3000 U.S. publicly traded companies. NASDAQ is an index of all the U.S. publicly traded companies which are traded on the NASDAQ exchange.

Table 2: Russell 3000 Regression Statistics

To analyze the effect of the Russell 3000 on art and real estate, I use a linear regression model. α indicates the intercept coefficient of the regression line. β indicates the sensitivity of the dependent variable to the Russell 3000. R2 indicates the proportion of the variance for the dependent variable explained by the Russell 3000. P-value (.05) is the statistical significance values < (.05) are statistically significant and values > (.05) are not statistically significant.

Table 3: NASDAQ Regression Statistics

To analyze the effect of the NASDAQ on art and real estate, I use a linear regression model. α indicates the intercept coefficient of the regression line. β indicates the sensitivity of the dependent variable to the NASDAQ. R2 indicates the proportion of the variance for the dependent variable explained by the NASDAQ. P-value (.05) is the statistical significance values < (.05) are statistically significant and values > (.05) are not statistically significant.

Table 4: S&P500 Regression Statistics

To analyze the effect of the S&P500 on art and real estate, I use a linear regression model. α indicates the intercept coefficient of the regression line. β indicates the sensitivity of the dependent variable to the S&P500. R2 indicates the proportion of the variance for the dependent variable explained by the S&P500. P-value (.05) is the statistical significance values < (.05) are statistically significant and values > (.05) are not statistically significant.

Table 5: Risk Characteristics

To compare the risk characteristics between art and real estate across the three independent variables, I calculated the systemic risk and noise using the standard deviation of the dependent variable and the R2 of the regression, respectively. The calculation for systemic risk, which measures the proportion of diversifiable risk, is (σ*R2). The calculation for noise, which measures the proportion of risk that is not diversifiable is (σ*(1-R2)).

Charts

References

Arena, J. (2022, February 16). Deutsche Bank’s John Arena: ‘Art lending is a simple proposition’ (Interview by Euromoney). Euromoney.

Ashenfelter, O., & Graddy, K. (2011). Sale rates and price movements in art auctions. The American Economic Review, 101(3), 212-216.

Bandle, A. L. (2015). Fake or fortune? Art authentication rules in the art market and at court. International Journal of Cultural Property, 22(2), 379-399.

Blackman, A. (2015, June 15). What’s That Hanging on Your Wall? Call it Collateral: Banks increasingly are offering loans secured by borrowers. The Wall Street Journal, Eastern Edition.

Bruno, B., Garcia-Appendini, E., & Nocera, G. (2018). Experience and brokerage in asset markets: Evidence from art auctions. Financial Management, 47(4), 833-864.

Cash in on your Picasso; Art-secured lending. (2019, July 6). The Economist (London), 58.

Fairfield, J. (2022). Tokenized: The law of Non-Fungible Tokens and unique digital property. Indiana Law Journal, 97(4), 1261-1313.

Etro, F., & Stepanova, E. (2021). Art return rates from old master paintings to contemporary art. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 181, 94-116.

Freddie Mac. (2023, April 6). [Primary Mortgage Market Survey] [Fact sheet]. Mortgage Rates.

Lack, J. (2016). LTV, Loan to Value. In For Rent By Owner: A Guide for Residential Rental Properties (p. 47). Atlantic Publishing Group.

Li, Y., Ma, X., & Renneboog, L. (2022). In Art We Trust. Management Science, 1-30.

Łydżba-Kopczyńska, B., & Szwabiński, J. (2022). Attribution markers and data mining in art authentication. Molecules, 27(1).

Medelyan, V. (2014). The art of a loan: When the loan sharks meet Damien Hirst’s ‘$12-million stuffed shark’. Pace Law Review, 35(2), 643-660.

Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2002). Art as an investment and the underperformance of masterpieces. The American Economic Review, 92(5), 1656-1668.

Neuhaus, N. M. (2015). Art lending: Market overview and possession of the collateral under Swiss law. Art, Antiquity, and Law, 20(2), 145-155.

Pearson, J. L. (2015, March 25). Establishing clear title to works of art (Art, Auctions and Antiquities). Wealth Management.

Ray, K. (2015). Art and Cultural Property. The Secured Lender, 71(3), 16-21.

Sotheby’s. (n.d.). The Value of Art [Video]. https://www.sothebys.com/en/series/the-value-of-art

St. Louis Federal Reserve. (2023). Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 30-Year Constant Maturity, Quoted on an Investment Basis [Fact sheet]. FRED.

The Washington Post. (2016, May 7). Case in Point: The fine art of financing art.

Weinberg, N. (2017, February 2). In JPMorgan’s ‘War Room,’ Private Banking meets cross-selling. Wealth Management.

Yu, B., & Gastwirth, J. L. (2010). How well do selection models perform? Assessing the accuracy of art auction pre-sale estimates. Statistica Sinica, 20(2), 837-852.

Zhukova, A., Lakshina, V., & Leonova, L. (2020). Hedonic Pricing on the Fine Art Market. Information (Basel), 11(5), 252.