College of Humanities

75 Discord between transgender women and TERFs in South Korea

Sooyoun Bae

Faculty Mentor: Scott Morris (Writing & Rhetoric, Asia Campus)

Abstract

This paper introduces the conflict between transgender women and trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs) in South Korea. Specifically, researchers state that the main reason TERFs exclude transgender people is the threat of anti-feminists these days, and this study will examine the discord between feminists and anti-feminists as well. In other words, the discourse of exclusion is created in order to protect themselves from attacks and threats. In addition, TERFs claim that trans women and feminists are incompatible since they believe trans women reinforce gender stereotypes. However, transgender people are suffering due to prevalent personal and systematic discrimination in society, and this paper suggests some specific incidents of the discrimination they are undergoing. Furthermore, it discusses the female-only spaces and the fear of men’s invasion, which leads to excluding trans women from these spaces.

Introduction

In South Korea, conflicts between transgender people and a group called TERFs are ongoing. TERFs often exclude trans women from the category of women, despite their female gender identity, and claim that trans women are against their ultimate goal: the dissolution of gender and patriarchy. As a result, transgender people are also alienated and experience discrimination against them. This paper will examine the conflict between TERFs and transgender women, focusing on the claims, hardships, and the meaning of women-only spaces to glance at both groups’ stances and further consider a more mature society.

The United States National Center for Transgender Equality (2016) defines transgender as “a broad term that can be used to describe people whose gender identity is different from the gender they were thought to be when they were born.” On the other hand, Miller and Yasharoff (2020) explain trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs) as a group of people who extremely prioritize women’s rights and resolutely oppose misogyny.

Stances of TERFs

The major reason TERFs exclude transgender people is that they deny the existence of gender identity itself. A cisgender woman named Maya Forstater posted that people cannot change their biological sex on her Twitter (Bowcott, 2019), saying, “There are two sexes. Men are male. Women are female. It is impossible to change sex. These were until very recently understood as basic facts of life” (Sullivan & Snowdon, 2019). Eventually, she was accused of using “offensive and exclusionary” language and opposing government proposals to accept people’s self-identity as the opposite sex” (Bowcott, 2019). J.K. Rowling, the author of the famous novel Harry Potter series, advocated Forstater and posted that it was unfair and extreme to fire her from the job for stating sex is real, and she was criticized as well for excluding transgender people (Sullivan & Snowdon, 2019).

Shared Experience of Misogyny

Following the instance mentioned above, TERFs in South Korea also highlight severe misogyny and emphasize protecting women’s rights. H. Lee (2019) analyzed that the background of TERFs is common experiences regarding sexual assaults, misogyny, and hate crimes, specifically after the Gangnam station murder case. A 34-year-old man murdered a woman in her twenties in a public restroom near Gangnam station, which is one of the most crowded areas in Seoul, on May 17, 2016 (Online News Team, 2016). The case has been controversy about whether it is a hate crime reflecting misogyny as the assailant said during the police investigation that he committed the crime because he felt like the victim had ignored him as other women did to him, even though they did not know each other personally (Online News Team, 2016). H. Lee (2019) found that this case triggered a lot of Korean women to recognize feminism and become feminists, and the unrest of women increased as the murder happened in a women’s restroom, which implies women cannot be safe even in female-only spaces. On May 17, 2021, some civic organizations participated in the struggle for the fifth anniversary of the Gangnam station murder and to win natural rights such as “the right not to be scared at night or anywhere, the right not to have anyone try to break into the house without permission, the right not to experience digital sex crimes, dating violence, and sexual violence forced by power” (News1, 2021). The researcher named Seunghwa Jeong (2018) analyzed that the ‘biological female’ category was initially constructed to defend from anti-feminists who use transgender rights to attack feminism rather than in order to exclude transgender women. Ri-Na Kim (2017), a researcher at the Korean Women’s Development Institute, examined the two most representative websites of radical feminists. In the article, she states that transgender women were naturally perceived as subjects of solidarity initially; however, transgender women and the category of women started to become controversial in August 2016 while preparing an online community for female sexual minorities. R-N. Kim (2017) also analyzes that transgender women’s femininity is regarded as exaggerated and wrong, and they have been blamed by radical feminists who claim that transgender women cause confusion on the category of women and “re/produce” existing femininity (p. 126).

Moreover, there are more severe and violent anti-feminism these days. A feminist organization named “Haeil,” which means tsunami in Korean, was attacked by an anti-feminist organization named “New Men’s Solidarity” on August 22, 2021, during the protest against the politicization of anti-feminism (Chaigne, 2021). The anti-feminists rushed into the protest, shouted assaulting words, threatened them, surrounded them with water guns, and said:

Look at all of these feminazis! That’s right, run away! At least you’ll get a bit of exercise! … So you got water on you? Are you angry? God, there are so many insects here, there are so many. I’m going to kill the insects, they’re insects, right? (The term ‘insect’ is used by some feminists to designate anti-feminists) … I heard that there were f*****g feminists here, I’m going to murder them all (Chaigne, 2021).

While the attack, Haeil had to cover their bodies and faces to protect their personal information since New Men’s Solidarity live-streamed the whole situation. Hae-in Shim, a member of Haeil, emphasized concealing their faces because the cybercrime of collecting and posting personal information, including photographs, is one of the most common against feminists (Chaigne, 2021).

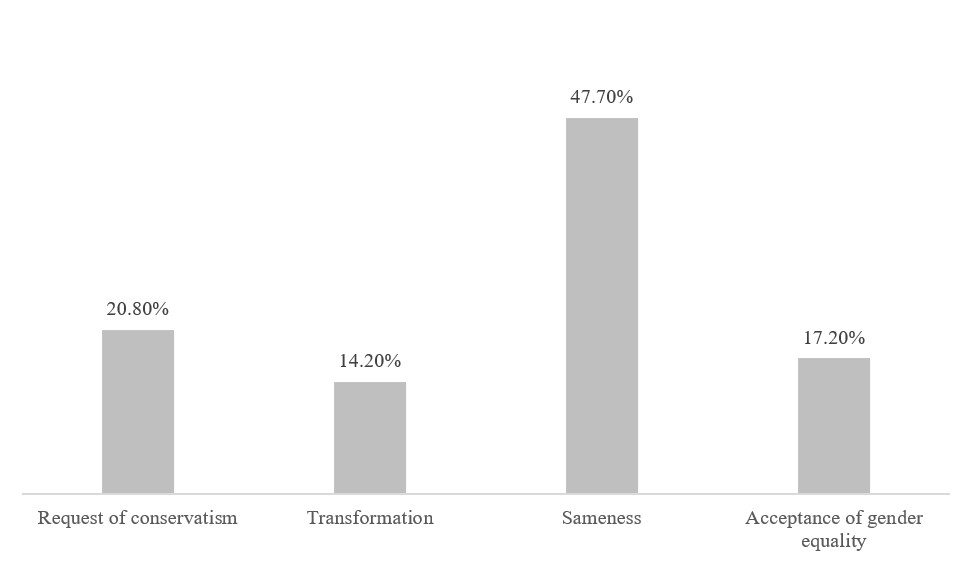

Furthermore, in an article named “Multi-layered gender perception among young men,” the author indicates that young female feminists are aware of daily misogyny and sexism. In contrast, a number of young males disagree with the context of structural sexism and strengthen anti-feminism (Choo, 2021). With the subjects of 3,435 males aged 19-34 in South Korea, Choo (2021) categorized participants into four types: request of conservatism, transformation, sameness, and acceptance of gender equality as a norm.

Figure 1: Ratios of four types

The “sameness” type (47.70%) opposes expanding legislation that would enhance the opportunity for women’s involvement since they regard that gender relations are currently equal. The author claims that while this type may seem to reflect anti-feminism, they advocate expanding the laws against workplace harassment and violence against women. The “request of conservatism” type (20.80%) is opposed to both passive and proactive sexist policies. According to the study, this type tends to refuse traditional gender roles and norms but views women as immature, whom males should protect rather than compete with. Additionally, this type opposes change and argues that the current system of oppression of women is reasonable. The “acceptance of gender equality as a norm” type (17.20%) supports the expansion of all gender equality laws, including proactive measures to combat sexism. Nonetheless, this type is highly resistant to paternity leave and males’ participation in housework, care, and gender equality, having the greatest acceptance of traditional gender role standards. Choo (2021) concludes that this type, although rejecting changes in everyday life and views regarding gender role norms, typically supports different gender equality initiatives. Finally, the “transformation” type (14.20%) is the last to reject conventional gender roles and think women are treated unfairly today. This type is the most welcoming to policies that combat sexism and protect and assist women, as well as governmental measures that can encourage males to improve and actively participate in reducing this inequality (Choo, 2021). This research demonstrates how feminism and women are now seen in South Korean society and suggest a broadened view of sexism and anti-feminism.

Reasons of Exclusion

A researcher also points out the irony that TERFs claiming biological sex are more legitimate than individuals’ gender identity (H. Lee, 2019). The author analyzes that TERFs in South Korea define femininity as misogynistic and reflects gender stereotype; therefore, they “set the ultimate goal and reason of feminism as abolishing gender” (p. 179). Furthermore, they contend that transgender people perpetuate gender norms and stereotypes, in contrast to the ‘escape the corset’ campaign, which began in 2017 and became widespread in 2018 (H. Lee, 2019). According to a CNN article titled “Escape the corset: How South Koreans are pushing back against beauty standards” (Jeong, 2019), the name of the movement was inspired by feminists’ 1968 Miss America beauty pageant protest, in which they threw away “bras, hairspray, makeup, girdles, corsets, false eyelashes, high heels.” This movement seeks to reject South Korean society’s ideals of beauty and the pressure to uphold them (Kuhn, 2019). As a result, many women take part in the movement by cutting their hair short, forgoing cosmetics, and dressing comfortably rather than in short, tight ensembles. Eventually, those women were the targets of assault and abuse by anti-feminists who assessed them based on their appearance.

Specifically, An San, a female archer from South Korea, won three gold medals in the Summer Olympics in 2021. However, a New York Times journalist reported that An San and other female athletes with short hairstyles at the Olympics had to face many online comments accusing her of being a feminist because of her short haircut (Jin, 2021). For instance, “Are you sure An San isn’t a feminist, … She meets all the requirements to be one” was one of the remarks on An’s Instagram. The article suggests that a professor of social network analysis at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Wonjae Lee, stated, “High-profile figures are often targeted by anti-feminists in South Korea” (Jin, 2021). The anti-feminists have become more combative and severe with women, seeing feminism as a perilous idea. According to a researcher named Hyomin Lee (2019), the feminist community is exclusive, specifically for male feminists, sexual minorities, including transgender people, and other women who are out of radical feminist boundaries. H. Lee asserts that TERFs describe gender as socially and culturally determined sex, and they think this emphasizes gender stereotypes concerning the exclusion of trans women. Consequentially, there is tension between TERFs and transgender women because TERFs believe that many transgender women exhibit stereotypical femininity, such as wearing sexually suggestive clothing and having long hair. They view these are contrary to radical feminists’ ultimate goal of gender dissolution and destroying the patriarchy, in accordance with the ‘escape the corset’ movement. In other words, TERFs in South Korea maintain that feminism and transgender rights are incompatible due to their conflicting stances (H. Lee, 2019).

Stances of Transgender People

Sarah McBride, a senator in Delaware of the United States and a spokesperson for the Human Rights Campaign, stated that TERFs view “deny the validity of transgender people and transgender identities” (McBride, 2020). Most feminists in the U.S., supporters of LGBTQ rights, and the mainstream medical community reject those views (Miller & Yasharoff, 2020). The American Medical Association (2018) emphasized that William E. Kobler, a board member, stated that sex and gender are much more complex than they are regarded and that restricted definitions of them may affect public health for transgender people and intersex people.

Personal Discrimination

Some people do not respect transgender people and ridicule or attack them, and transgender people in South Korea face online discrimination. For example, a Twitter user once mocked trans people by posting, “I am a trans cat because I feel I am a cat. If you cannot understand me, you are a trans cat phobia” (H. Lee, 2019, p. 182). Likewise, H. Lee (2019) introduces several malicious comments and Twitter postings against transgender people in the article “Radical Reconstruction of Feminist Politics.” According to the author, biology, notably sex chromosomes, is a major factor in TERFs’ denial of transgender people’s existence and their lives. The following YouTube comment prominently demonstrates the thoughts:

The biggest dilemmas: 1) If you think you are a black person, can you be a black person? 2) If you think you are a cat, are you a cat? 3) If someone considers oneself an armless disabled person and tries to cut off their own arm, would it be an identity, not a mental illness? 4) Why ignore the basic scientific common sense that chromosomes determine sex? 5) What is a woman’s mind/spirit? I will be a TERF until someone who can clearly answer these five questions appears. (H. Lee, 2019, p. 181).

In other words, TERFs believe that biology is the absolute fact and common sense, and they emphasize the unchangeability of gender from birth, while they regard gender identity as an illusion. Since TERFs claim that “feeling” oneself as another gender regardless of the biological sex is illogical, they often mock transgender people; for example, belittling transgender people by setting the nickname “trans…” can be found online. Their central point is to stress that gender identity is an illusion and that the only and absolute fact is the biological sex from birth.

In February 2020, a trans woman student became qualified to enter a women’s university in South Korea (Jang, 2020). Although she had already finished sex-change surgery in 2019 and successfully completed gender recognition, many enrolled students objected to her matriculation after learning of her admittance through news articles by calling the school’s admissions office as a group and sending protest emails to the alumni association. Additionally, radical feminist clubs from more than 20 institutions created a social media account and published a statement against the student’s enrollment and, saying, further opposing sex change that jeopardizes biological women’s rights (Sookmyung Women’s University T.F. Team X Against Transgender Male’s Admission, 2020). One of the enrolled students mentioned the following in an interview:

Women’s college was created for women with fewer opportunities from birth than men to education and social advancement. … People who enter women’s college are those who were born as women and have been socially discriminated against and oppressed. I do not understand why a person who has lived as a man until last year wants to enter a women’s college (Jang, 2020).

On the other hand, several students did hold the firm belief that in order for a society to be mature, neither the institution nor the students should exclude or denigrate any particular gender identity (Jang, 2020). On Facebook, a statement supporting the student claimed that South Korean women’s universities were founded on the ideology of granting social minorities, particularly women, the same rights to education (The Student and Minority Human Rights Commission of Sookmyung Women’s University, 2020). In other words, the commission determined that the fundamental purpose of women’s institutions is to address prejudice and pursue equality. Thus, they claimed that rejecting a specific person’s identity and debating whether or not to allow her admission was against the university’s philosophy (The Student and Minority Human Rights Commission of Sookmyung Women’s University, 2020). The transgender student did, however, eventually renounce attending the university on the very last day for students to determine their enrollment (Kwon & Kang, 2020). She confessed that she felt fearful and heartbroken all day long for being cursed after seeing every comment and response about her (Kwon & Kang, 2020). She also discussed another incident when she went to the office of education to register for the national college entrance exam while wearing a one-piece dress, typically considered a women’s outfit. A staff member reprimanded her attire and advised her that it would be better to dress “normally” because, saying, other students might feel uneasy on the day of the exam. She eventually had to switch to wearing pants instead of skirts. Before giving up on getting into the university, she said in the interview that she would be dedicated to informing the public about how anybody can be a minority in specific circumstances to emphasize the significance of equality. She expressed her wish that society would embrace each individual more and said that if individuals did not want to face prejudice and contempt in any other situations when they are a minority, they should appreciate and respect minorities of different identities (Kang, 2020).

Legal and Systematical Discrimination

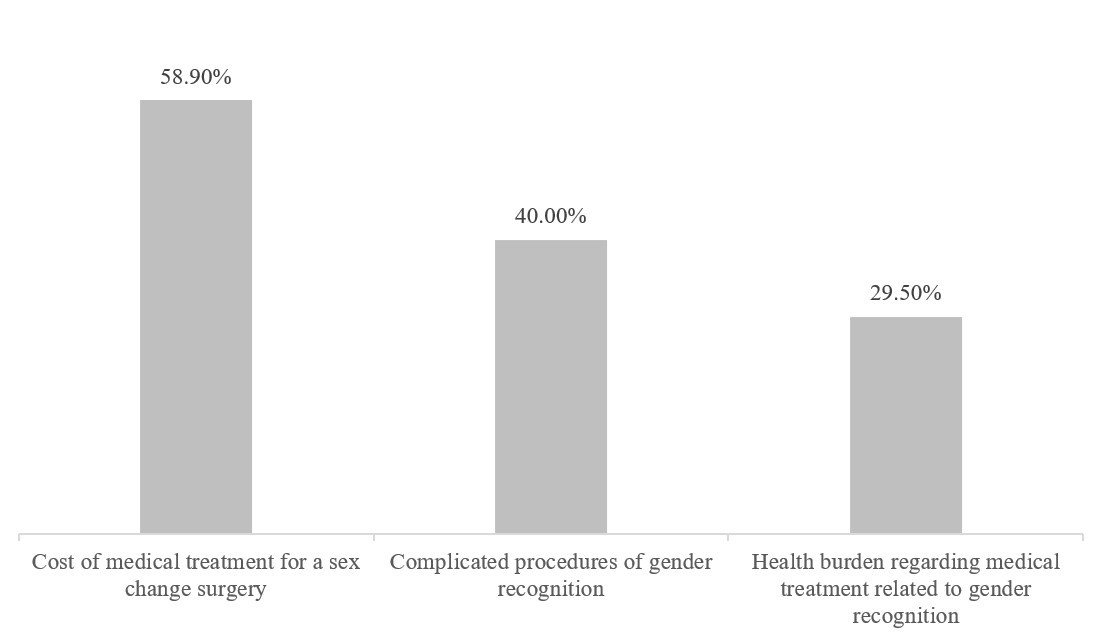

Research on transphobia and discrimination in South Korea was undertaken in 2020 by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRCK), which also revealed the struggles transgender individuals face daily (Hong et al., 2020). In an online poll, 591 South Koreans over 19 identifying themselves as transgender were asked to discuss their experiences in nine different categories, including gender recognition. As a result, only 47 participants (8.0%) said that they had successfully completed the legal process of gender recognition, 28 people (4.7%) were making progress, and 508 individuals (86.0%) had never attempted it. The participants’ failure to attempt gender recognition was attributed to three main reasons:

Figure 2: Causes of not trying gender recognition

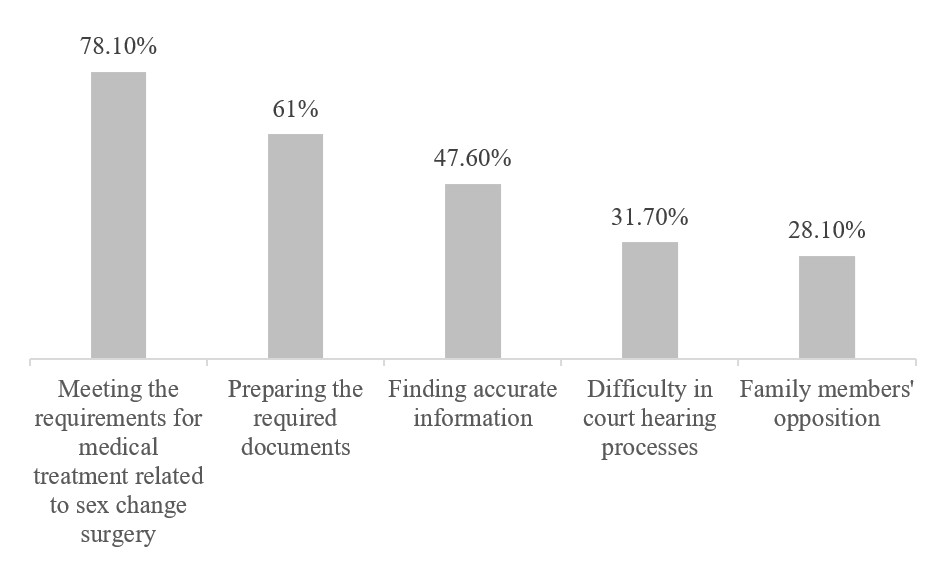

Furthermore, five critical factors were revealed by 82 subjects who have done or tried gender recognition:

Figure 3: Hardships during gender recognition

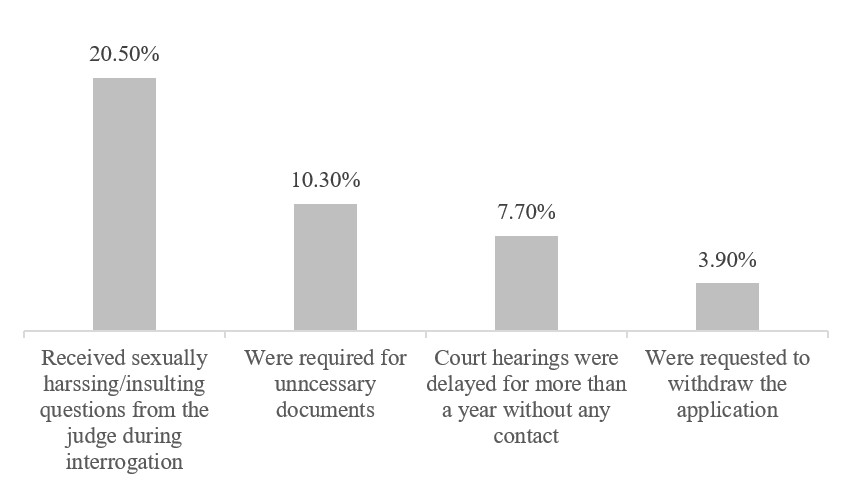

Finally, 78 participants answered that they encountered unfairness as a result of the gender recognition procedure (Hong et al., 2020):

Figure 4: Injustice during the gender recognition process

Although South Korea does not currently have a law addressing the gender recognition of transgender people, there are guidelines that fall under Article 104 of the Act On Registration Of Family Relations (Rectification of Inadmissible Records Entered in Family Relations Register) (Korean Legislation Research Institute, 2019). According to the Supreme Court of Korea’s guidelines, the following documents are required or optional:

- A certificate of identification documents

- A psychiatrist’s medical certificate or written appraisal that identifies the applicant as a transgender patient

- A letter of opinion from a sex-change surgery doctor that confirms that the applicant currently has a contrary appearance (i.e., look like) to biological sex

- A medical certificate or written appraisal verifies that the applicant does not currently have a reproductive ability and is unlikely to occur or recover in the future

- The applicant’s growth environment statement and acquaintance’s warranty (Supreme Court of Korea, 2020)

A tragedy involving legal and systematical discrimination occurred in March 2021 when Huisu Byeon, a trans woman, took her own life at the age of 23 (W. Kim, 2021). She became aware of her gender identity during Korean mandatory military service and was advised to get surgery by the Armed Forces Capital Hospital after being identified as having significant gender dysphoria (W. Kim, 2021). Ultimately, she gained approval for a furlough overseas and underwent sex change surgery (Yu, 2021). She wanted to stay in the military because her dream was to become a soldier. Still, the Discharge Review Committee forced her to discharge from the army in January 2020 due to a mental and physical disorder, suggesting the loss of her phallus and testicles as evidence of her “disorder” (Yu, 2021). The army adhered to the decision even though the NHRCK urged the military to postpone the review for three months. Byeon subsequently petitioned the Daejeon District Court to object to the discharge on August 11, 2020. Six months after Byeon’s lawsuit was filed, the court set the first hearing date for April 15, 2021, after the U.N. sent a document to the Korean military stating that forcing her discharge violated international human rights law. The Military Human Rights Center’s secretary-general, Hyungnam Kim, expressed his sorrow at Byeon’s suicide by saying the following:

I often resented the judiciary. Byeon could not even stand in court once because the court dawdled. … When the military (the executive branch) disregarded Byeon, both the court (the judicial branch) and legislative branch, who were not interested in enacting anti-discrimination laws, joined the silence (W. Kim, 2021).

On March 16, 2021, at the National Assembly Defense Committee, the Minister of National Defense articulated the need for studies on the military service of transgender persons after Huisu Byeon’s story gained widespread public awareness (W. Kim, 2021).

Female-Only Spaces

Definition & Necessity

Sheila Jeffreys, a well-known radical feminist in the United Kingdom, studied separatism and stressed the value of places exclusively for women (Jeffreys, 2018a). The formation of female-only areas is the most fundamental type of separatism, according to Jeffreys, who claimed that the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) in the U.K.’s early 1970s applied the concept of separatism. She even asserted that “any attempt to create women-only space is challenged and sometimes threatened by men’s rights activists and men who transgender” (Jeffreys, 2014, as cited in Jeffreys, 2018a, p. 55). The Free Space leaflet from the very beginning of the WLM organization in the U.S. declares, “We do not allow men in our movement because in a male supremacist society, men can and do act as the agents of our oppression” (Allen, 1970, as cited in Jeffreys, 2018a, p. 57). She also underlined the need for women-only places since Jeffreys (2018b) expressed fear that women would be unable to express their challenging ideas in the presence of males, the oppressors who can interrupt, become agitated or threaten them. In this context, Jeffreys emphasized the necessity for a safer location, contending that women are more likely to experience male violence in settings with mixed genders (Romito, 2008, as cited in Jeffreys, 2018a). She asserted that the premise for advocating for female-only spaces is to define “women” as a political category created by patriarchal oppression resulting from living as a woman in a society where men are in charge (Jeffreys, 2018b).

Korean Female-Only Spaces

Various women-only facilities are already sprouting in South Korea, including parking areas, lounges, taxicabs, libraries, and fitness centers. However, there are differing views on whether or not certain areas are for women’s safety and whether they constitute reverse discrimination against males. The supporters claim that the rates of sex crime against women are considerably greater than those against males. According to the report of the Korean National Police Agency (2021), 20,041 out of 21,717 sex crime instances involved female victims, which was 92.29% of the total. A news article stated that women-only facilities are appropriate for women’s protection and claimed to have insights about their objectives by suggesting the statistics that around 40.27% of sex offenses occurred in environments that were known to everyday life (Democratic Press Citizens’ Union, 2019). According to an article named “Women-only Space” (Ko, 2016), the construction of these places is due to visualized women’s social achievements in Korean society in the late 1990s. Females’ social successes—for example, passing national examinations, enrolling in colleges, and finding employment rather than staying home to care for the family—were seen as men’s struggles or crises. Since people blamed feminist movements and even all women in these critical situations, Ko (2016) explains that women-only spaces were one tactic to maintain women’s voices facing harsh surroundings. In particular, the female student lounges in several coeducational universities in the capital region started to take shape in the late 1990s and early 2000s in response to demands of female students, which were prompted by common issues such as exclusion from cultures where men predominated and the need for networks as empowered spaces (Ko, 2016).

On the other hand, one particular case displays the idea that males are subjected to reverse discrimination due to female-only areas or services nowadays. In Jecheon-si, South Korea, there was a dispute in 2021 about the women-only library (S. Lee, 2021). With all the money she earned from sewing, an older woman named Hak-im Kim purchased and donated the land for the Jecheon Women’s Library, which opened in 1994. Her goal was to resolve the discrimination against women seeking higher education. However, a man in his twenties claimed to the NHRCK in 2011 that it discriminates against men, and the commission urged the city and the library twice the following year. The city argued that the women-only library adheres to the donor’s wishes and is irrelevant to sexism. Jecheon-si also elaborated on Kim’s satisfaction and pride in the library during her lifetime, as well as her family’s hopes to continue operating in accordance with its original purpose. The NHRCK, nonetheless, determined that putting the donator’s personal will ahead of a public facility’s intended use is challenging since the national property legislation specifies that the donator’s objective has no bearing on the law. The city argued in response that the library did not entirely exclude males because men are allowed to borrow books with the assistance of the staff, boys under the age of 10 can use the facility with a female caregiver, and the library has plans to have a family reading program. Yet, the NHRCK rejected such assertions and concluded that the library excessively restricted men’s usage since there are no men’s restrooms and men are not permitted in the material rooms. Although there is a city library close to the women’s library, the commission claimed significant disparities in proximity while utilizing public transit. In the end, the library partially complied with the commission’s exhortation and has let men borrow books since July 2021, but a library official the library is not considering additional actions, such as constructing men’s restrooms (S. Lee, 2021). This specific incident indicates the ongoing argument about women-only facilities.

Fear of Invasion of Female-Only Spaces by Men

Regarding the aforementioned incident of the trans woman student and women’s university, a student who was against the enrollment stated in one interview that she felt uncomfortable after a series of events in males intruding on campus (Jang, 2020). She described two instances: one in which a male drug offender hid in the university’s student union restroom and the other in which a man trespassed on a school lavatory while dressed like a woman. Even if there are no exact statistics, B. Lee and H. Kim (2020) describe a few particular incidents demonstrating how women’s universities in Korea have been at risk from strangers’ invasions. Specifically, a male student from another university broke into Sookmyung Women’s University in April 2017 and was later detained on suspicion of sexual harassment. Also, after a male stranger engaged in indecent behavior while unclothed in a lecture room in October 2018, Dongduk Women’s University barred unauthorized visitors. Moreover, Ehwa Woman’s University increased the installation of security cameras and card readers at the entrance of the buildings following the accusation that a male office worker broke into the campus and touched a sleeping female student’s body. Thus, several women’s institutions decided to restrict visitors after encountering hidden camera crimes or males trespassing into the facilities (B. Lee & H. Kim, 2020).

In this context, Jeong (2018) claims that not just online sexism but also daily sexual abuse has led to the desire for a safe space exclusively for women. Furthermore, radical feminists in South Korea have experienced high levels of sexual stress due to pervasive sex crimes, according to Jeong’s (2018) analysis. This high sexual stress is caused by men invading women’s spaces due to misogyny and sex crimes, including hidden camera crimes and the murder case at the Gangnam station. This claim corresponds to the abovementioned analysis that the “biological women” category discourse was constructed as a defense rather than to exclude trans women. Thus, the author examines that women in South Korea demand women-only spaces for safety and the power to voice and resist unreasonable misogyny today (Jeong, 2018).

Conclusion

Regardless of conflicting stances, it is true that both transgender people and feminists are those who should be respected. Due to concern for their safety and other factors, TERFs in South Korea began to reject transgender people. They refuse to embrace trans women as females whom they should protect by feminist goals for women’s rights. However, although the exclusion has started to protect themselves, it is true that transgender people, in this study notably trans women, have experienced personal and institutional exclusion and discrimination. Both males and females otherize transgender persons and alienate them from society. By setting stricter standards for other social groups, which likewise divides individuals, the discord between two groups may ultimately lead to increased and expanded exclusion. Feminism is a vital social movement for women’s rights, but it is crucial to resolve the conflicts rather than excluding others based on rigid criteria for the category of women. Thus, reconsidering the definition and standards of females may help accept individuals to make a mature and welcoming society for every person.

References

American Medical Association. (2018, November 13). AMA adopts new policies at 2018 INTERIM Meeting. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-adopts-new-policies-2018-interim-meeting

Bowcott, O. (2019, December 18). Judge rules against researcher who lost job over transgender tweets. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/dec/18/judge-rules-against-charity-worker-who-lost-job-over-transgender-tweets

Chaigne, T. (2021, September 14). The South Korean men waging a vulgar and violent war against feminists. The Observers – France 24. https://observers.france24.com/en/asia-pacific/20210914-the-south-korean-men-waging-a-vulgar-and-violent-war-against-feminists

Choo, J. (2021). Cheong-nyeon Nam-seong-deul-ui Jen-deo In-sig Da-cheung-seong [Multi-layered gender perception among young men]. Han-Gug-Yeo-Seong-Hag [Journal of Korean Women’s Studies], 37(4), 155–193. https://doi.org/10.30719/jkws.2021.12.37.4.155

Democratic Press Citizens’ Union [민주언론시민연합]. (2019, September 16). Yeo-seong-jeon-yong-si-seol-i saeng-gyeo-nan maeg-lag-eul i-hae-hae-ya [We Need to Understand the Context of Women-Only Facilities]. Media Today. http://www.mediatoday.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=202364

Gug-ga-in-gwon-wi-won-hoe [National Human Rights Commission of Korea], Hong, S., Kang, M., Kim, S., Park, H., Lee, S., Lee, H., Lee, H., Jeon, S., Kim, R., Mun, Y., Eom, Y., & Ju, S., Teu-laen-seu-jen-deo Hyeom-o-cha-byeol Sil-tae-jo-sa [Transgender Hate Discrimination Survey] (2020).

Jang, W. (2020, February 2). “Seong-jeon-hwan Nam-seong Ib-hag Ban-dae” Sug-myeong-yeo-dae-seo Hag-nae Ban-bal Um-jig-im [Sookmyung Women’s University Protests Against Admission of Transgender Woman]. Yonhapnews. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20200201046200004?input=1195m

Jeffreys, S. (2018). Lae-di-keol Pe-mi-ni-jeum [Radical Feminism]. (Y. Kim, H. Nam, H. Park, Y. Lee, & J. Lee, Trans.). Yeolda Bukseu.

Jeffreys, S. (2018). The Lesbian Revolution: Lesbian Feminism in the Uk 1970-1990. Taylor & Francis Group.

Jeong, S. (2018). Geub-jin pe-mi-ni-jeum-eul kwi-eo-hyeom-o-lo-bu-teo gu-hae-nae-gi: Yeo-seong-un-dong-gwa seong-so-su-ja un-dong-ui yeon-dae-leul wi-han si-lon [Rescuing Radical Feminism from Queer Hate: A Theory for the Solidarity between the Women’s Movement and the LGBT Movement]. Mun-Hwa-Gwa-Hag [Cultural Science], (95), 50–73.

Jeong, S. (2019, January 12). Escape the corset: How South Koreans are pushing back against Beauty standards. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/south-korea-escape-the-corset-intl/index.html

Jin, Y. Y. (2021, August 30). She just won her third gold medal in Tokyo. Detractors in South Korea are criticizing her haircut. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/30/sports/olympics/an-san-hair.html

Kang, J. (2020, February 2). Sug-myeong-yeo-dae Cheo-cho Teu-laen-seu-jen-deo Hab-gyeog-saeng “Ma-eum Neo-deol-neo-deol-hae-jyeoss-da” [Sookmyung Women’s University’s First Passed Transgender Student “My Heart Is Tattered”]. The Hankyoreh. https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/926586.html

Kim, R.-N. (2017). Me-gal-li-an-deul-ui ’yeo-seong’ beom-ju gi-hoeg-gwa yeon-dae: “Jung-yo-han geon ’nu-ga’ a-nin u-li-ui ’gye-hoeg’i-da.” [The Megalians’ Project of the Category of Women and the Solidarities: “The Important Thing is not ‘Who’ but Our ‘Plan’.”]. Journal of Korean Women’s Studies, 33(3), 109–140. https://doi.org/10.30719/jkws.2017.09.33.3.109

Kim, W. (2021, March 21). “Sa-beob · Ib-beob · Haeng-jeong-bu Mo-du Byeon-hui-su-leul Oe-myeon-haess-da” [The Judicial, Legistlative, and Administrative Governments All Turned a Blind Eye to Byeon Huisu]. The Kyunghyang Shinmun. https://www.khan.co.kr/national/national-general/article/202103210807011

Ko, Y.-K. (2016). Yeo-seong-jeon-yong-gong-gan [Women-only Space]. Yeo/Seong-i-Lon [Journal of Feminist Theories and Practices], (35), 167–180.

Korea Legislation Research Institute. (2019). Act On Registration Of Family Relations. Dae-han-min-gug Yeong-mun-beob-lyeong [Republic of Korea Law in English]. https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=54145&lang=ENG

Korean National Police Agency, 2020 Beom-joe-tong-gye [Korean Police Crime Statistics in 2020] (2021).

Kuhn, A. (2019, May 6). South Korean women ‘escape the corset’ and reject their country’s beauty ideals. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2019/05/06/703749983/south-korean-women-escape-the-corset-and-reject-their-countrys-beauty-ideals

Kwon, J., & Kang, J. (2020, February 7). Sug-dae Teu-laen-seu-jen-deo Hab-gyeog-saeng Gyeol-gug Ib-hag Po-gi “Sin-sang-yu-chul Deung Mu-seo-um Keoss-da” [Passed Student at Sookmyung Women’s University Eventually Gave up Admission “I Was Scared of Personal Information Leakage and So Forth”. The Hankyoreh. https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/927386.html

Lee, B., & Kim, H. (2020, February 21). Bul-an-i-lan I-leum-ui ‘Hyeom-o’ … Teu-laen-seu-jen-deo Bae-je-han ‘Teo-peu’ Hae-bu-ha-da [“Hate” in the Name of Anxiety … Dissecting “TERF” That Excludes Transgender People]. The Kyunghyang Shinmun. https://www.khan.co.kr/national/national-general/article/202002210600015

Lee, H. (2019). Pe-mi-ni-jeum jeong-chi-hag-ui geub-jin-jeog jae-gu-seong: Han-gug’ TERF’-e dae-han bi-pan-jeog bun-seog-eul jung-sim-eu-lo [Radical Reconstruction of Feminist Politics: Focusing on the Critical Analysis of “TERF” in South Korea]. Media, Gender & Culture, 34(3), 159–223. https://doi.org/10.38196/mgc.2019.09.34.3.159

Lee, S. (2021, July 10). “Yeo-seong-jeon-yong-eun nam-seong cha-byeol”… Yeo-seong-deul bun-no-han in-gwon-wi gwon-go, eo-tteoh-ge bwa-ya hal-kka [“Women-Only Facilities Are Discrimination Against Men”… How Should We View National Human Rights Commission of Korea’s Exhortation That Made Women Furious?]. The Women’s News. https://www.womennews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=213588

McBride, S. (2020, March 8). About Sarah. Sarah McBride. https://sarahmcbride.com/about-sarah/

Miller, R. W., & Yasharoff, H. (2020, June 9). What’s a TERF and why is ‘Harry Potter’ author J.K. Rowling being called one? USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/06/09/what-terf-definition-trans-activists-includes-j-k-rowling/5326071002/

National Center for Transgender Equality. (2016, July 9). Understanding transgender people: The basics. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/issues/resources/understanding-transgender-people-the-basics

News1. (2021, May 17). ‘Gang-nam-yeog Sal-in-sa-geon’ 5Ju-gi… “Jen-deo-gal-deung A-nin Seong-cha-byeol ⸱ Yeo-seong-hyeom-o” [5th Anniversary of “Gangnam Station Murder”…”It’s Not Gender Conflict, It’s Gender Discrimination and Misogyny”]. dongA.com. https://www.donga.com/news/Society/article/all/20210517/106987080/1

Online News Team. (2016, May 18). Gangnam-yeog han-bog-pan-seo “Yeo-ja-deul-i na-leul mu-si-haet-da” mut-ji-ma sal-in [A Random Murder Happened in Gangnam Station Saying, “Women have ignored me”]. The Kyunghyang Shinmun. http://sports.khan.co.kr/news/sk_index.html?www&art_id=201605181037003

Sookmyung Women’s University T.F. Team X Against Transgender Male’s Admission [숙명여자대학교 트랜스젠더남성 입학반대 TF팀 X] [@smwuwomyn]. (2020, February 6). Yeo-dae yeon-hab seong-myeong-mun. [Yeo-seong-ui gwon-li-leul wi-hyeob-ha-neun seong-byeol-byeon-gyeong ban-dae-had-da]] [A statement from the association of Women’s Universities. [We oppose gender recognition that threatens women’s rights]] [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/smwuwomyn/status/1225382782106386433

The Student and Minority Human Rights Commission of Sookmyung Women’s University [숙명여자대학교 학생•소수자 인권위원회]. (2020, February 2). Si-dae-ui yo-cheong-e eung-dab-hal geos-in-ga, hyeom-o-ui pyeon-e seol geos-in [Will you respond to the demands of the times, or will you stand by the hate?] [Image attached]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/100175401452787/photos/a.122986409171686/140433374093656/

Sullivan, R., & Snowdon, K. (2019, December 20). JK Rowling under fire over transgender comments. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2019/12/20/uk/jk-rowling-transgender-tweets-scli-intl-gbr/index.html

Supreme Court of Korea. (2020). Seong-jeon-hwan-ja-ui Seong-byeol-jeong-jeong-heo-ga-sin-cheong-sa-geon Deung Sa-mu-cheo-li-ji-chim [Guidelines for Handling Affairs of Transgender People Applying for Permission for Gender Recognition] . Dae-han-min-gug Beob-won Jong-hab-beob-lyul-jeong-bo [Korean Courts Comprehensive Legal Information]. https://glaw.scourt.go.kr/wsjo/gchick/sjo330.do?contId=3226349#1642204985543

Yu, H. (2021, March 4). ‘Seoung-jeon-hwan Gang-je-jeon-yeog’ Byeon-hui-su Jeon Ha-sa Sug-je Nam-gi-go Tteo-na-da [Former Staff Sergeant Huisu Byeon “Forced Discharge Due to Sex Change” Passed Away Leaving Homework]. Yonhapnews. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20210303181600504?input=1195m