School of Medicine

50 A Descriptive Analysis of Night Eating Behaviors and Circadian Timing

Mohammad Alrayess

Faculty Mentor: Kelly Baron (Family and Preventive Medicine, University of Utah)

Abstract

Objective: Eating during the biological night is associated with poorer metabolic health. The goal of this study is to examine habitual night eating, eating behaviors in a standardized laboratory task and circadian timing in an ongoing study of circadian

rhythms and eating behaviors.

Methods: Data are derived from a larger ongoing study that focuses on sleep, circadian timing and risk factors for type 2 diabetes. Participants completed self-report questionnaires to assess habitual frequency of night eating and actigraphy to measure sleep. Eating behaviors at night were measured using an eating in the absence of hunger task administered at 21:00. Circadian timing was determined by dim light melatonin onset (DLMO). Metabolic assessments included BMI. This study presents descriptive analyses.

Results: Participants seem to consume more calories of sweet foods compared to neutral foods which seems to correspond with previous studies. Additionally, it seems that participants are able to report their night eating behavior, but are uncomfortable labeling themselves as “night eaters”.

Conclusion: This descriptive analysis possibly provides a useful insight on how prevalent night eating might be and the possible eating behaviors during a laboratory task. In the future, analysis of the relationship between DLMO and eating behaviors will be examined.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity in America has been increasing at an alarming rate for many years. Studies show that around 41.9% of Americans are considered to be obese with 9.2% of them being severely obese (Fryar et al., 2020). Many complications can arise due to obesity which include heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers (Fryar et al., 2020). Current recommendations largely focus on diet and physical activity to manage obesity risk (CDC, 2020). A growing area specifically is studying the timing of eating throughout an individual’s day. Recently, research has started to focus on late night eating as there might be a potential physiological mechanism which contributes to an increase risk of obesity.

Night eating is considered to be a delayed timing of an individual’s meal time which is typically their evening meal (Martinez-Lozano et al., 2020). Identifying whether an individual has night eating behaviors is defined differently across studies, however, several studies define night eating as more than 25% of daily caloric intake after one’s evening meal (Tholin et al., 2009). Studies show that night eating seems to be fairly prevalent among adults. One study observed that the prevalence among nonobese men and women seem to be around 4.6% and 3.4% respectively compared to an increase in prevalence among obese men and women with numbers around 8.4% and 7.5% (Tholin et al., 2009). Many issues could arise with night eating. Some studies show that night eating is associated with increased hunger and decreased energy expenditure among obese individuals (Vujović et al., 2022). With this, there has been progress with understanding the relationships between night eating and obesity.

Eating at night may increase hedonic eating, or eating for pleasure. One study highlights that the most commonly consumed food type are snacks and sweets in the late evening (Sebastian et al., 2019). With the timing of food consumption and the types of food being eaten, it is currently understood that this phenomenon might be related to disruption of the body’s clock, circadian rhythm (Mendoza, 2019).

In addition, eating at night may be related to disruptions of the circadian rhythm. Studies have shown that meal timings play a role with regulating circadian timing (Wehrens et al., 2017). This is crucial because disrupting one’s circadian rhythm leads to unwanted health consequences. One possible consequence that was observed is increased insulin resistance when eating during the biological night (Stenvers et al., 2019). Few studies have quantified eating behaviors relative to the internal biological rhythm. In terms of measuring these timings, the dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) is used as a biomarker for circadian rhythm and this might influence the metabolic impact of late eating.

A limitation of prior research is that we do not understand how eating relative to DLMO affects eating behaviors and risk for obesity/diabetes. Understanding possible different eating behaviors is crucial since excessive caloric intake is a prime driver for weight gain (Romieu et al., 2017). Understanding an eater’s experience with their late-night snacks is essential as well due to the idea that positive eating experiences with hedonic eating is possibly correlated with an increase in appetite (Monteleone et al., 2012).

The objective of this study is to test the relationship between eating in the biological night (after DLMO) with hedonic eating behaviors and metabolic health. In this thesis, we will present descriptive analyses related to the night eating and circadian variables. We will also present our next step planned analyses for next steps to evaluate if those who eat more in the biological night will have poorer metabolic health.

METHODS/DESIGN

Participants

This is a secondary analysis of a longitudinal study that evaluated associations between sleep duration, circadian rhythm, and cardiometabolic health among overweight adults (Baron et al., 2023). Participants were recruited through different means such as flyers through the University of Utah campus, advertisements on websites such as Facebook and Reddit, and participant registries. Participants that were eligible for the study included adults aged 18 to 55 years with a BMI around 25.0-34.9 kg/m^2. They must also sleep on average around 10:30 PM – 3:00 AM which was verified by 7 days of wrist actigraphy. Exclusion criteria include: 1) Chance of having sleep disorders which were assessed with questionnaires and overnight OSA screening; 2) diabetes diagnosis; 3) history of cognitive or neurological disorders; 4) Presence of major psychiatric disorders as well as possible substance abuse measured with screening questionnaires; 5) Serious medical conditions; 6) Inflexible or overnight work schedules; 7) Any substances that may affect melatonin concentrations such as antidepressants; 8) Current smokers; 9) Daily caffeine intake above 300 mg; 10) Pregnant. (Baron et al., 2023). Once the participants were eligible, the participant inclusion criteria for this study includes that the participant must at least complete the day B visit listed under the longitudinal study. From there, the participant was able to answer the questionnaire related to this study as well as be considered for this study.

Procedure

After pre-screening, participants were scheduled for a screening/baseline visit to determine the participant’s eligibility for the study and measure baseline values. The visit included informed consent, HbA1c, height, weight and body fat. After the visit, participants were sent home with a one-night Apnea link to screen for OSA and an actigraphy to help confirm their sleeping times. Participants were eligible for study once they met this criterion (Baron et al., 2023).

Participants completed a circadian phase assessment where saliva samples containing melatonin were collected every 30 minutes starting 6.5 hours before the participant’s average bedtime. The lights were dimmed 30 minutes before their first saliva sample and it stayed dim until their average bedtime. Average bed times were estimated by using wrist actigraphy. Participants were instructed to refrain from caffeine and alcohol use for 24 hours before the first saliva sample. Additionally, they were instructed to refrain from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for at least 72 hours before saliva collection.

The eating in absence of hunger task was to measure eating habits within the morning at 9:00 AM and evening at 8:00 PM. Participants were asked to fill out hunger and appetite questionnaires before and after each task. First participants consumed a bowl of plain oatmeal until they stated that they were comfortably full. Then, after a 20-minute waiting period, they were presented with a taste test which had different arrays of palatable and neutral foods such as Oreos or Cheerios and each participant was asked to rate each food on taste, enjoyability, and perception. The study team tracked how much was eaten within each task without the participant’s knowledge initially. For the purpose of this study, participants who have at least completed the day B protocol will be considered for this study’s purposes as this study is only analyzing evening eating habits.

Measures

Demographics

Participants completed a questionnaire regarding demographics including their sex, age, ethnicity, race, employment, income, and marital status.

Circadian Measures

DLMO was assessed for each individual’s profile. This was done by assessing the specific clock time where melatonin initially increases above the average three low daytime values and twice the standard deviation of the baseline values set (Baron et al., 2023). Circadian alignment was calculated by using the participant’s DLMO duration and comparing it with the participant’s average bed time (Baron et al., 2023).

Evening Calorie Consumption

Calorie consumption of each food item was collected. This was calculated by taking the measured amount of food eaten of each food item and converting that into calories by using the nutritional label associated with each food item.

Taste Testing Rating Form

Measuring participant’s self-report of their experience, taste, and enjoyability of certain food items during taste test.

Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ)

A self-report questionnaire given past participant’s day B protocol asking them to report on their assessment on habitual night eating. Questionnaires was either administered through email or during their lab visit. Relevant questions were collected from Night Eating Diagnostic Questionnaire (Geliebter, 2017).

Metabolic Measures

A Tanita scale was used to collect the BMI of every participant.

RESULTS

Demographics

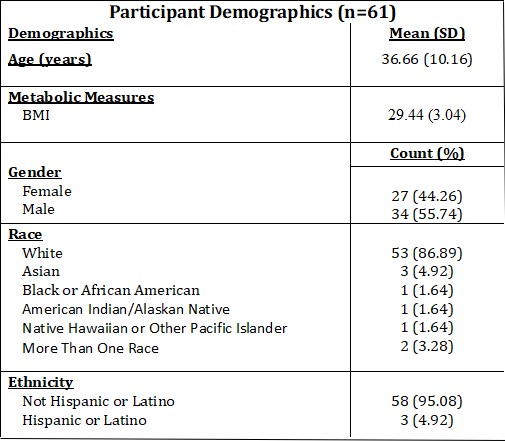

Demographics were collected and results are shown in Table 1 for the 61 participants who completed a questionnaire regarding their demographics. Furthermore, metabolic measures were collected during the first visit of the participant. BMI averages were calculated (Table 1).

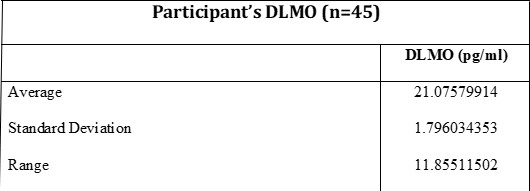

Dim Light Melatonin Onset

Of the sample set currently, the average DLMO was calculated (9:00 PM) with the standard deviation. The range of the data was also calculated (Table 2).

Eating in Absence of Hunger Task

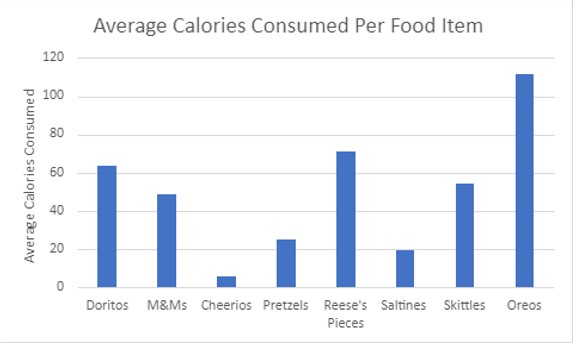

Participant’s average calories consumed per food item offered to them during the task was calculated (Figure 1). Oreos, Reese’s Pieces, and Doritos were reported to have the most calories consumed during the task on average. On average, Cheerios and Saltines were the food items that were consumed the least.

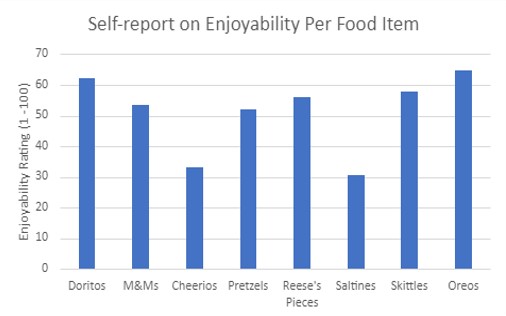

Participants self-reported their experience of how they enjoyed each food item offered. The average ratings (1-100) were calculated from all participants (Figure 2).

Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ)

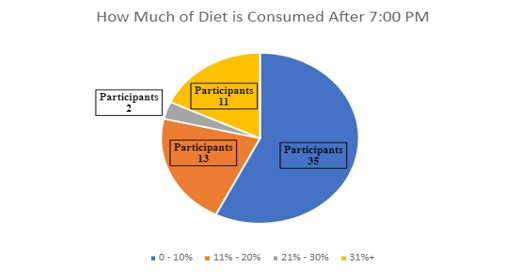

Participants were asked to self-report how much of their daily caloric intake is after 7:00 PM. Majority reported that 0-10% of their diet comes after 7:00 PM (Figure 3).

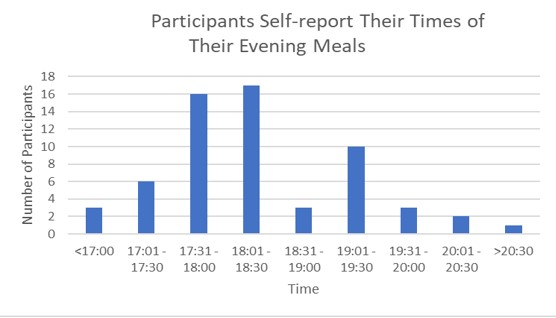

Additionally, participants were asked to self-report their evening meal times. Majority of participants reported their evening meal times to be around 5:30 PM – 6:30 PM (Figure 4).

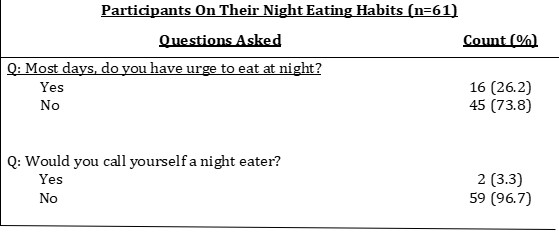

Participants were asked to describe their own night eating behaviors and what would they label themselves as (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The goal of this descriptive analysis is to examine the prevalence of night eating and eating behaviors in a standardized laboratory task to help further understand these factors and how they might pertain to the overall long-term goal of the study. The long-term goal of this study is to examine evening eating habits compared to individuals’ DLMO times. Possible findings could contribute to a better understanding of diseases such as obesity and type II diabetes. Overall, we found that participants consumed a greater number calories of calorie-dense, sweet foods and rated enjoyment higher for these foods as well, even among participants who did not report habitual night eating. Additionally, some participants self-reported to have night eating behaviors (i.e., 26.2% reported having urges to eat at night on most days), but did not label themselves as “night eaters” (3.3%). Finally, participants self-reported their evening meal times with an average of 6:30 PM being calculated and how much of their daily caloric intake is after 7:00 PM with the majority being less than 10%. With this data, there is some analysis that can be done to further understand these data points.

When looking at the average calories consumed, it is intriguing how many of the participants seem to prefer to consume a lot more calories of the sweeter, more calorie-dense foods compared to the neutral foods offered during the task. At first, this might seem obvious, but when considering the fact that these participants were asked to sample these food items in absence of hunger, one would expect them to eat similar proportions for each food item. However, this does not seem to be the case. Studies have shown that there is evidence of hedonic hunger which is eating for pleasure and that individuals that are considered obese tend to consume a larger portion of high palatability foods compared to normal weight individuals (Lowe & Butryn, 2007). With that, the BMI reported might demonstrate the study’s observation since the reported average BMI would be considered to be in the overweight range. This means that these participants might have undergone hedonic eating which could explain the high number of calories consumed for the unhealthy foods even with absence of hunger. More analysis would be needed to observe this relationship.

Additionally, the NEQ results that were collected demonstrated very few participants considered themselves “night eater” (3.3%). This is especially interesting when considering that studies report that younger adults tend to show signs of night eating and it seems to be more apparent as one ages (Striegel-Moore et al., 2006). When considering the average age of the sample was 37 years, out of these participants, one would expect that more of them would self-report as being night eaters. One possible explanation for this observation could be the result of the social desirability bias aspect in this case. When participants were asked to label themselves as night eaters, one might perceive this label to be undesirable. This might be especially true when considering that 26.2% of the participants reported to have some night eating behaviors Reporting their own night eating behaviors seems to be a relatively comfortable task for the participants to do, but labelling their own behaviors with a term might be making them uncomfortable. More analysis and testing would be needed to identify whether the social desirability bias is a factor in this case.

The participant’s evening meal times were recorded and majority seemed to eat their dinner between 5:30 PM – 6:30 PM. Studies show that the average evening meal time is around 6:22 PM (Larson, 2002). This seems to match up with the average evening meal times assessed with the NEQ. Additionally, this seems to be consistent whenever considering how much of the participant’s daily caloric intake is after 7:00 PM. Majority of the participants self-reported that 0-10% of their diet is consumed after 7:00 PM. This is consistent with studies that report that 25% of daily calories come from their evening meals (Striegel-Moore et al., 2006). This is relevant as it seems to support the idea that the calories consumed from the evening meals is independent of the excess calories consumed during night eating if it occurs. Understanding this possibility is crucial as it allows for proper analysis of night eating behaviors with these participants. More analysis would be needed such as food diaries to properly understand whether the foods eaten later in the day are associated with commonly eaten foods during night eating.

This study is still on-going. In the next steps, we plan to analyze whether biological timing (DLMO) is associated with hedonic eating behaviors in the eating in absence of hunger task as well as reports of habitual night eating on the NEQ. The calculated average DLMO time was found to be around 9:00 PM. Of these times, 55.6% of the participants had DLMO times below the average and 44.4% of participants had DLMO times above. In the future, this could be analyzed to see whether these participants tended to consume more calories in general compared to individuals who had a DLMO time before the eating in absence of hunger task.

Our study had several limitations. One limitation are the evening meal times reported could be a case of cultural evening meal times. Depending on the culture, evening meals are consumed at a variety of different times which does not allow for consistency in this aspect. Another limitation is small sample size. Therefore, we may not have the statistical power for comparisons in future analyses. Furthermore, our assessments of eating behaviors were based on self-report habitual intake and a standardized laboratory task. Food diaries were not collected from the participants during this study and may have been a more accurate representation of night eating. Strengths of the study include objective measures of biological timing (DLMO) and measurement of eating behaviors both in the lab and through self-report.

CONCLUSION

This descriptive data analysis possibly provides an insight of night eating behaviors and how individuals might think of their own behaviors. Possible night eating behaviors could have been demonstrated with the observation of increased calorie-intake of sweeter foods among individuals with an average BMI that falls within the overweight range. Furthermore, it seems to be that individuals seem willing to report their own night eating behaviors, however, they feel uncomfortable labeling themselves as “night eaters” which might be associated with a social desirability bias. This is especially true when considering that participants reported times of meals that seem to be consistent with other studies emphasizing that the participants are consistent with their responses The next steps would be to analyze the possible night eating behaviors in relation to their DLMO time and to possibly further analyze why individuals report their night eating behaviors the way they do.

This study is still on-going; however, the long-term goal is to analyze the relationship between DLMO and eating behaviors in the eating in absence of hunger task. Analysis of this relationship will be able to provide more insight of the data collected and demonstrated within this descriptive data analysis. With this, proper steps can be suggested in trying to aid this issue.

References

Baron, Kelly & Appelhans, Brad & Burgess, Helen & Quinn, Lauretta & Greene, Tom & Allen, Chelsea. (2023). Circadian Timing, Information processing and Metabolism (TIME) study: protocol of a longitudinal study of sleep duration, circadian alignment and cardiometabolic health among overweight adults. BMC endocrine disorders. 23. 26. 10.1186/s12902-023-01272-y.

CDC – National Center for Health Statistics – Healthy Weight, Nutrition, and Physical Activity. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/index.html. June 3, 2022.

Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Afful J. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and severe obesity among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 1960–1962 through 2017–2018. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2020.

Geliebter, Allan. (2017). Night Eating Diagnostic Questionnaire (NEDQ) Revised (9/2014). 10.13140/RG.2.2.10472.78089.

Larson, Ronald B.. “When Is Dinner.” Journal of food distribution research 33 (2002): 38-45.

Lowe, M. R., & Butryn, M. L. (2007). Hedonic hunger: a new dimension of appetite?. Physiology & behavior, 91(4), 432–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.006

Mendoza J. (2019). Food intake and addictive-like eating behaviors: Time to think about the circadian clock(s). Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 106, 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.07.003

Monteleone, P., Piscitelli, F., Scognamiglio, P., Monteleone, A. M., Canestrelli, B., Di Marzo, V., & Maj, M. (2012). Hedonic eating is associated with increased peripheral levels of ghrelin and the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol in healthy humans: a pilot study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 97(6), E917–E924. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-3018

Romieu, I., Dossus, L., Barquera, S., Blottière, H. M., Franks, P. W., Gunter, M., Hwalla, N., Hursting, S. D., Leitzmann, M., Margetts, B., Nishida, C., Potischman, N., Seidell, J., Stepien, M., Wang, Y., Westerterp, K., Winichagoon, P., Wiseman, M., Willett, W. C., & IARC working group on Energy Balance and Obesity (2017). Energy balance and obesity: what are the main drivers?. Cancer causes & control : CCC, 28(3), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-017-0869-z

Sebastian, R. S., Wilkinson Enns, C., Goldman, J. D., & Moshfegh, A. J. (2019). Late Evening Food and Beverage Consumption by Adults in the U.S. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2013-2016. In FSRG Dietary Data Briefs. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Stenvers, D. J., Scheer, F. A. J. L., Schrauwen, P., la Fleur, S. E., & Kalsbeek, A. (2019). Circadian clocks and insulin resistance. Nature reviews. Endocrinology, 15(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-018-0122-1

Striegel-Moore, R.H., Franko, D.L., Thompson, D., Affenito, S. and Kraemer, H.C. (2006), Night Eating: Prevalence and Demographic Correlates. Obesity, 14: 139-147. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.17

Tholin, S., Lindroos, A., Tynelius, P., Akerstedt, T., Stunkard, A. J., Bulik, C. M., & Rasmussen, F. (2009). Prevalence of night eating in obese and nonobese twins. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 17(5), 1050–1055. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.676

Vujović, N., Piron, M. J., Qian, J., Chellappa, S. L., Nedeltcheva, A., Barr, D., Heng, S. W., Kerlin, K., Srivastav, S., Wang, W., Shoji, B., Garaulet, M., Brady, M. J., & Scheer, F. A. J. L. (2022). Late isocaloric eating increases hunger, decreases energy expenditure, and modifies metabolic pathways in adults with overweight and obesity. Cell metabolism, 34(10), 1486–1498.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.007

Wehrens, S. M. T., Christou, S., Isherwood, C., Middleton, B., Gibbs, M. A., Archer, S. N., Skene, D. J., & Johnston, J. D. (2017). Meal Timing Regulates the Human Circadian System. Current biology : CB, 27(12), 1768–1775.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.059